Nighttime Snowstorms May Swirl Across Mars

Mars may experience snowstorms at night, a new study finds, suggesting that the Martian atmosphere is far more active than previously thought.

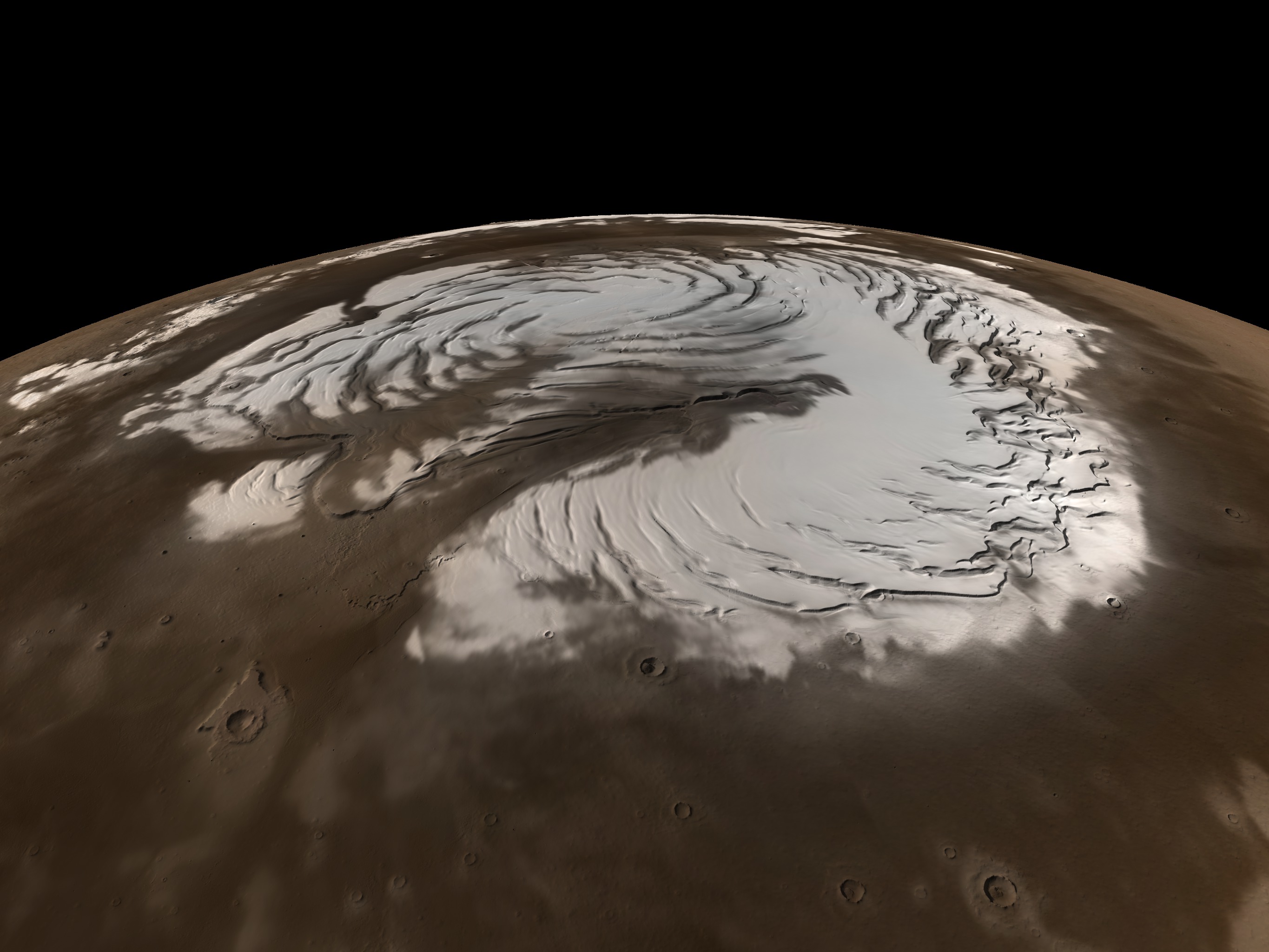

Mars is dry compared to Earth: Its cold nature makes it unlikely that any of the ice on the Red Planet's surface would melt, and its extremely thin atmosphere would cause any liquid water on the surface to vaporize nearly immediately. Still, Mars' atmosphere does possess clouds of frozen water.

Previous research suggested that if snow did fall from those clouds, it would waft down very slowly. "We thought that snow on Mars fell very gently, taking hours or days to fall 1 or 2 kilometers [0.6 to 1.2 miles]," said study lead author Aymeric Spiga, a planetary scientist at the University of Pierre and Marie Curie in Paris. [Photos: Most Powerful Storms of the Solar System]

Now, Spiga and his colleagues have found that snow can rapidly descend on Mars in storms. "Snow could take something like just 5 or 10 minutes to fall 1 to 2 km [0.6 to 1.2 miles]," Spiga told Space.com.

The researchers were analyzing data from NASA's Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft when they noticed a strong mixing of heat in the Martian atmosphere at night "about 5 km [3 miles] from the surface," Spiga said. "This was never seen before.

"You expect heat to get mixed in the Martian atmosphere close to the surface during the daytime, since the surface gets heated by the sun," Spiga explained. "But my colleague David Hinson at Stanford University and the SETI Institute saw it higher up in the atmosphere and at night. This was very surprising."

To explain these findings, the researchers developed an atmospheric model to simulate the weather on Mars. "It took something like three to four years to come up with a model sophisticated enough to reproduce Mars' clouds," Spiga said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists discovered that the cooling of water-ice cloud particles during the cold Martian night could generate unstable turbulence within the clouds.

"This can lead to strong winds, vertical plumes going upward and downward within and below the clouds at about 10 meters [33 feet] per second," or about 22 mph (36 km/h), Spiga said. "Those are the kinds of winds that are in moderate thunderstorms on Earth."

Snow can get caught inside these winds and rapidly fall downward. The researchers said that such Martian snowfall is analogous to small, localized storms on Earth called microbursts, in which cold, dense air carrying snow or rain gets rapidly transported downward from a cloud.

Any snow landing on Mars would not last long. Once the sun rises, any water ice on the surface would turn to vapor, "unless it was in a very cloudy region or high latitudes," Spiga said.

If the clouds the snow falls from are more than about 1.2 miles (2 km) from the Martian surface, the snow might turn to vapor before it even hits the surface, Spiga added. "This is something observed on Earth sometimes, with something called virga — streaks of rain falling from the clouds can vaporize before reaching the surface," he said.

Martian snowstorms could explain previously unexplained signs of snow detected in 2008 by the laser scanner aboard NASA's Phoenix lander.

"We are able to explain two different mysterious and surprising observations with a single meteorological phenomenon — these snowstorms," Spiga said.

These findings suggest that the Martian atmosphere is more dynamic than previously thought. "Since you have these powerful winds, these are able to vigorously mix anything, such as heat, water, methane, ozone, dust," Spiga said. "We can now use this data to see what impact these winds have on, say, how water moved from one region to another on Mars in the present and past."

Future research will aim to get more glimpses of these Martian snowstorms, Spiga said. "We want to look all over Mars and see when they happen at night, and what seasons they occur and the effect they have on a global scale," he said.

The scientists detailed their findingsonline yesterday (Aug. 21) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us