This Enzyme Enabled Life to Conquer A Hostile Earth

Computers are simulating the ancestral versions of the most common protein on Earth, giving scientists an unparalleled look at early life's development of harnessing energy from the sun and production of oxygen.

These findings could shed light on the evolution of alien life elsewhere in the Universe, researchers said. They recently detailed their findings in the online version of the journal Geobiology.

Photosynthesis, which uses energy from sunlight to create sugars and other carbon-based organic molecules from carbon dioxide gas, has played a major role in Earth's history. Photosynthesis supports the existence of plants and other photosynthetic organisms across Earth's lands and seas, which in turn sustains complex webs of animal and other life. It also generates the oxygen gas that has chemically altered the face of the planet. [Early Earth: A Battered, Hellish World with Water Oases for Life]

Although oxygen currently makes up about a fifth of the Earth's atmosphere, very early in the planet's history, oxygen was rare. "Our planet has, for much of its history, resembled an altogether alien place," said Betül Kacar, an evolutionary biologist and astrobiologist at Harvard University.

The first time the element suffused Earth's atmosphere to a great extent was about 2.5 billion years ago in what is called the Great Oxidation Event. Prior research suggests this jump in oxygen levels was almost certainly due to cyanobacteria — microbes that, like plants, photosynthesize and produce oxygen.

Studying how life evolved in the alien conditions of Earth's deep past may shed light on "conditions that may more closely align with the temperature or atmospheric compositions of a wide variety of planets outside our Solar System," Kacar said. In other words, research into early life on Earth could help us understand possible alien life on distant exoplanets.

The first major step of photosynthesis is triggered by an enzyme known as Rubisco. Previous research suggested that Rubisco is likely the most abundant protein on Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Rubisco's job is to take in carbon dioxide from the environment so that it can be turned into biological matter," Kacar said.

Many versions of Rubisco exists across a broad range of organisms, from plants to bacteria. Much remains uncertain about when Rubisco evolved and how it diversified over time because of the meager fossil record of early life on Earth. Learning more about the evolution of Rubisco could shed light on what early photosynthesis was like and what changes it wrought on Earth. Such findings could yield insights into what effects alien versions of photosynthesis might have on distant planets.

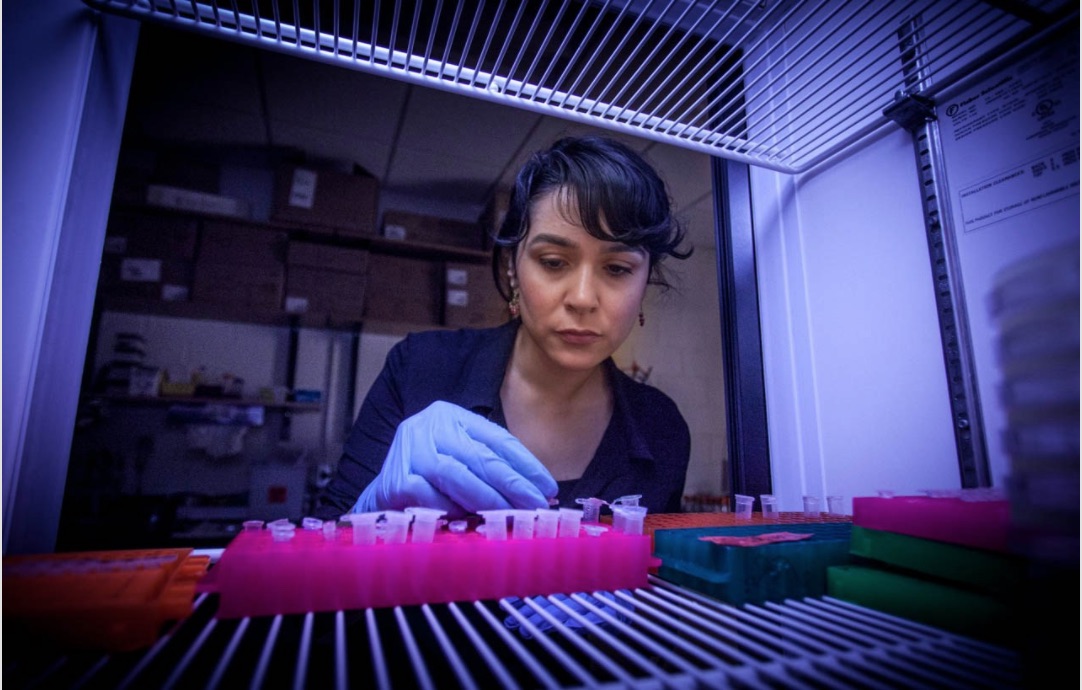

To figure out the Rubisco family tree, Kacar and her colleagues used computer models to analyze the molecular structures of different versions of Rubisco. Comparing and contrasting different versions of Rubisco can shed light on how closely or distantly related all these proteins may be to each other.

This work helped the scientists deduce the possible structures of ancient members of the Rubisco family tree. The scientists next resurrected these ancestral proteins on the computer to see how these structures might have once behaved.

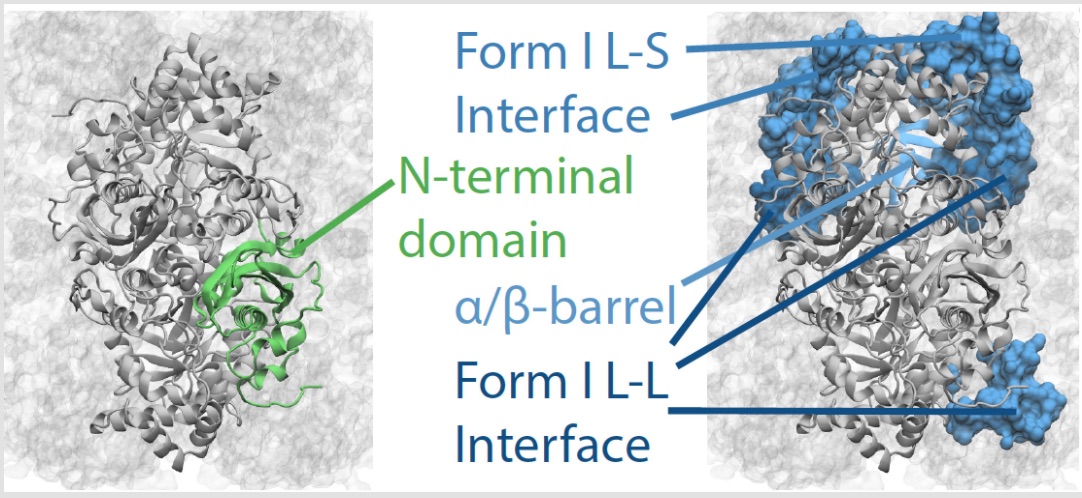

There are four major groups, or forms of Rubisco and Rubisco-like proteins. The scientists focused on so-called Form I and Form III groups. Form I proteins are associated with oxia, or oxygen-loaded air, and include the forms of Rubisco that are dominant today. Form III enzymes are associated with anoxia, or a lack of oxygen, and previous research suggested they may be the ancestors of all the other Rubisco groups.

The new findings suggest that Rubisco apparently underwent a great deal of change during the divergence between Form I and Form III types of Rubisco. This suggests that oxygen, which was poisonous to early life on Earth, spurred these changes.Specifically, the researchers suggest that some forms of Rubisco adapted to the presence of the oxygen it indirectly helped to generate. These forms of Rubisco developed in order to not mistake oxygen for carbon dioxide.

"Carbon dioxide and oxygen are about the same size and have similar chemical characteristics, so Rubisco can confuse the two molecules," Kacar said. "When Rubisco takes in oxygen instead of carbon dioxide, it is not possible to make biomass because there is no carbon in oxygen."

Ultimately, the researchers want to create microbes that possess ancestral versions of Rubisco. They can then compare the chemical traits of such microbes to the chemical compositions of ancient rocks to learn more about what events might have occurred in the early Earth, Kacar said.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. Follow Space.com @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us