No End to Saturn's Mysteries in Cassini's Closing Days

It might as well be the mission motto: "Saturn continues to surprise us."

That's what Earl Maize, project manager for the Cassini mission at Saturn, said during a news conference today (Aug. 29). He was referring to the fact that the inner ring system where the Cassini probe is spending some of its final weeks doesn't have as much dust as scientists anticipated, and is therefore not as harsh on the spacecraft's instruments. If the mission could last longer — if the probe weren't running out of fuel, that is — Maize said he'd love to have Cassini explore that region longer.

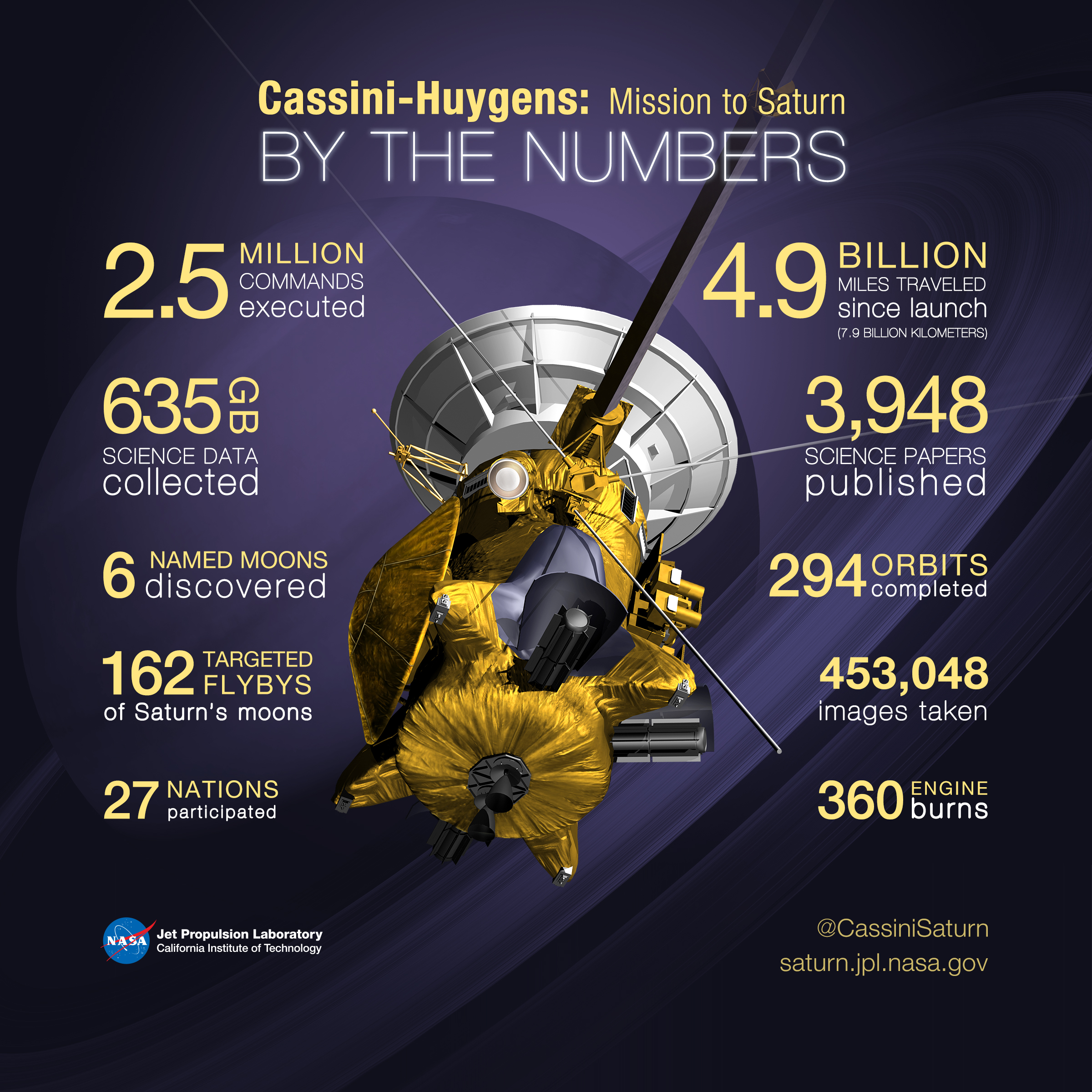

This trend of finding surprising or unexpected physical characteristics — of Saturn and its moons — has characterized Cassini's entire 13-year stint in the Saturnian system, the scientists said, and continues to prove true in the probe's very last weeks. On Sept. 15, Cassini will complete its "Grand Finale" set of maneuvers and crash into Saturn's atmosphere, transmitting data back to Earth right up until the spacecraft breaks apart. [Cassini's 'Grand Finale' at Saturn: NASA's Plan in Pictures]

On its current trajectory, Cassini has also taken the first-ever in-situ samples of Saturn's atmosphere, and Linda Spilker, the Cassini project scientist, said those early results suggest that the chemical and dynamic interactions between particles from the planet's rings and the planet's upper atmosphere are "more complex … than we had both anticipated."

That's good news, she said, because "scientists love mysteries, and the Grand Finale is providing mysteries for everyone."

Ongoing mysteries

Cassin began its "Grand Finale" in April, and the first fruits of new science from that curtain call are already sprouting, NASA scientists said during today's news briefing.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For the last few months, Cassini has been looping through Saturn's inner ring system and sampling the top of the planet's atmosphere, which is "like dipping our toe in Saturn's atmosphere, in preparation for the final plunge," Spilker said during the news briefing.

From those initial tastes of Saturn's atmosphere, Cassini scientists are already finding "incredible, intriguing information" about how the material from Saturn's ring system mixes with the upper layers of the planet's atmosphere. On Sept. 15, the probe will plummet to depths of up to 9,300 miles (15,000 kilometers).

"By having in-situ sampling of the atmosphere, we can directly measure things like the hydrogen-to-helium ratio," Spilker said. Both Jupiter and Saturn consist largely of hydrogen and helium, but the ratios of these two elements can help scientists learn about how and when those planets formed, as well as the nature of the solar system at that time.

"We can directly measure composition of … constituents at a very, very low level in the atmosphere — things that would be much harder to see from a distance with remote sensing and spectroscopy," she said.

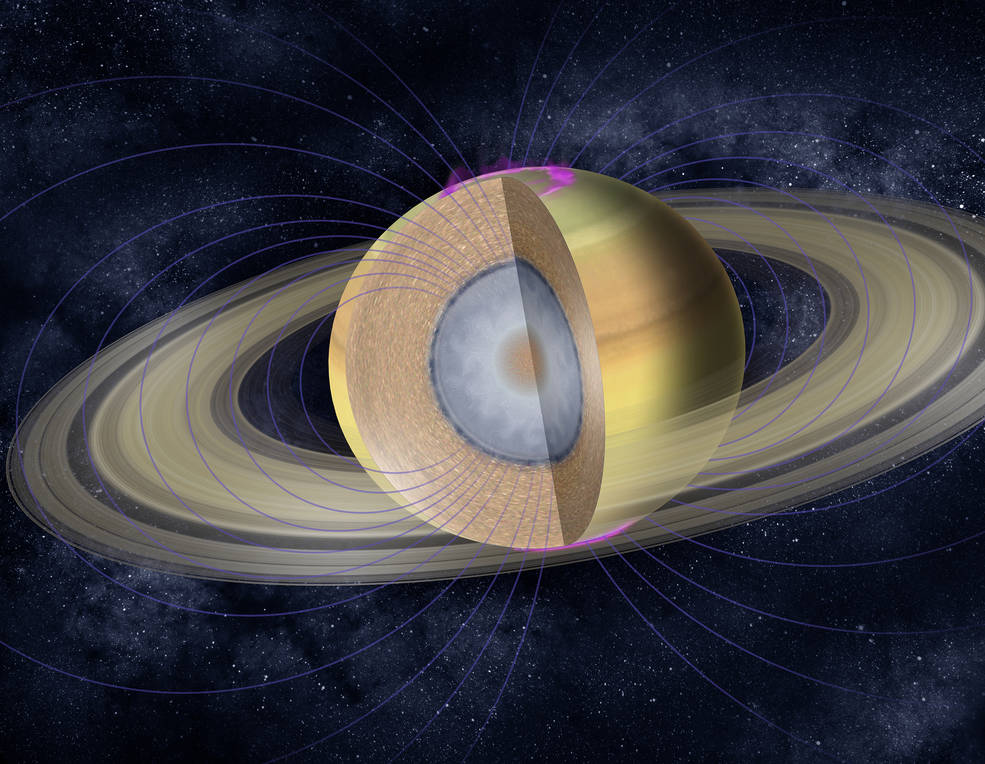

Spilker said scientists also hope that Cassini's plunge will help them understand the nature of Saturn's magnetic field source, the mass of its rings, and the exact length of its day (the time it takes the planet to spin once on its axis).

Getting that data back to Earth before Cassini is destroyed has required a change in the probe's basic data-transmission system, the scientists said. Typically, Cassini stores its data on a hard drive and transmits the information back to Earth much later, but during its final plummet, Cassini will sop up information from the planet and transmit it back to Earth almost immediately. That direct transmission will start about 3 hours before Cassini hits Saturn's atmosphere.

"A 2- to 3-second latency is all we're expecting," Maize said (referring to the time between Cassini collecting data and transmitting it). "So, we will have repurposed Cassini into an atmospheric probe, and we will have it broadcasting data back down to the very last minute." [Photos: Saturn's Glorious Rings Up Close]

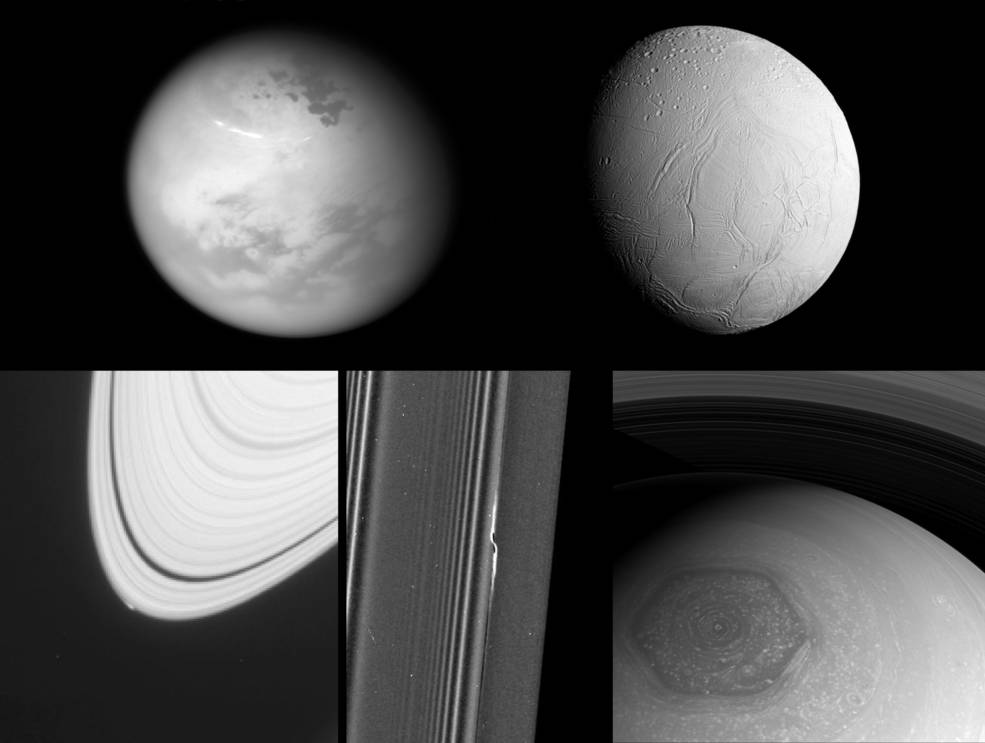

The last picture show

On Sept. 13 and 14, Cassini will conduct what the NASA team is calling the "last picture show," Maize said, when the probe's camera will take its final images of the Saturn system. The probe won't have the transmission bandwidth to send back images during the 3-hour period just before reaching Saturn's atmosphere on Sept. 15.

"These final images are kind of like taking a last look around your house or apartment just before you move out," Spilker said. "You walk around the downstairs; as you go upstairs, you run your fingers along the bannister; you look at your old room as memories across the years come flooding back.

"In the same way, Cassini is taking a last look around [the] Saturn system, Cassini's home for last 13 years," she said. "And with those pictures come heartwarming memories."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter