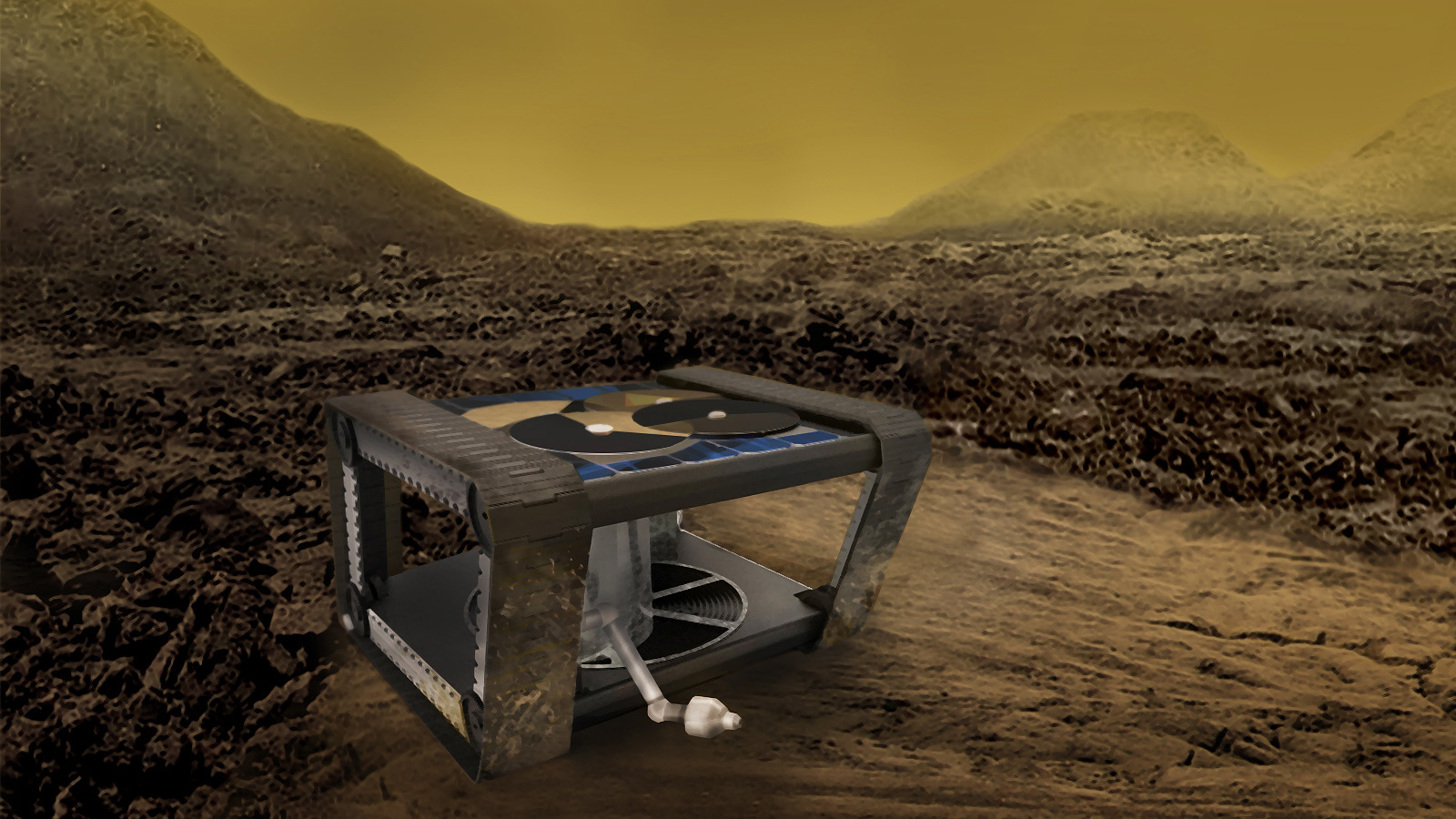

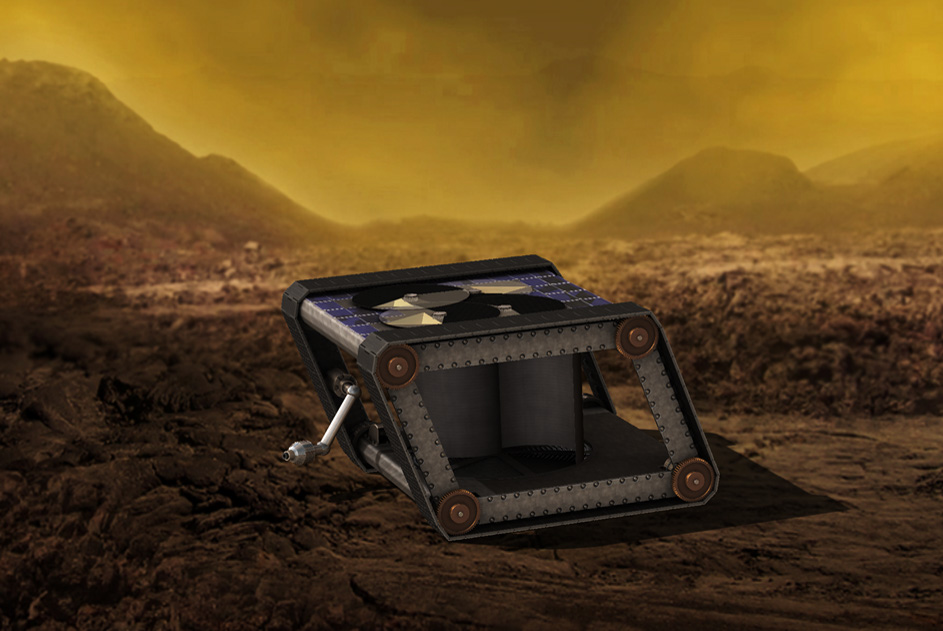

This Venus rover concept looks like something out of science fiction — from the 19th century.

Researchers are studying the possibility of building a steampunk Venus rover, which would forsake electronics in favor of analog equipment, such as levers and gears, to the extent possible.

"Venus is too inhospitable for the kind of complex control systems you have on a Mars rover," project leader Jonathan Sauder, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "But with a fully mechanical rover, you might be able to survive as long as a year." [Photos of Venus, the Mysterious Planet Next Door]

"Inhospitable" may be a bit of an understatement. Thanks to Venus' thick atmosphere, pressures on the planet's surface are high enough to crush the hull of a nuclear submarine, NASA officials said. That same atmosphere has also spawned a runaway greenhouse effect: Venus' average surface temperature is a whopping 864 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius) — hot enough to melt lead (not to mention standard electronics).

No spacecraft has ever survived these conditions for more than 127 minutes, and none has even tried for more than three decades; the last probes to reach the Venusian surface were the Soviet Union's twin Vega 1 and Vega 2 landers, which launched in 1984.

So Sauder and his team are thinking creatively, drawing inspiration from mechanical computers such as Charles Babbage's famous 19th-century Difference Engine and the intricate Antikythera mechanism, which the ancient Greeks used to predict eclipses and perform a variety of other celestial calculations.

They're developing their concept vehicle, known as the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE), using two rounds of funding from the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program. NIAC grants are intended to help nurture potentially revolutionary space science and exploration ideas.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

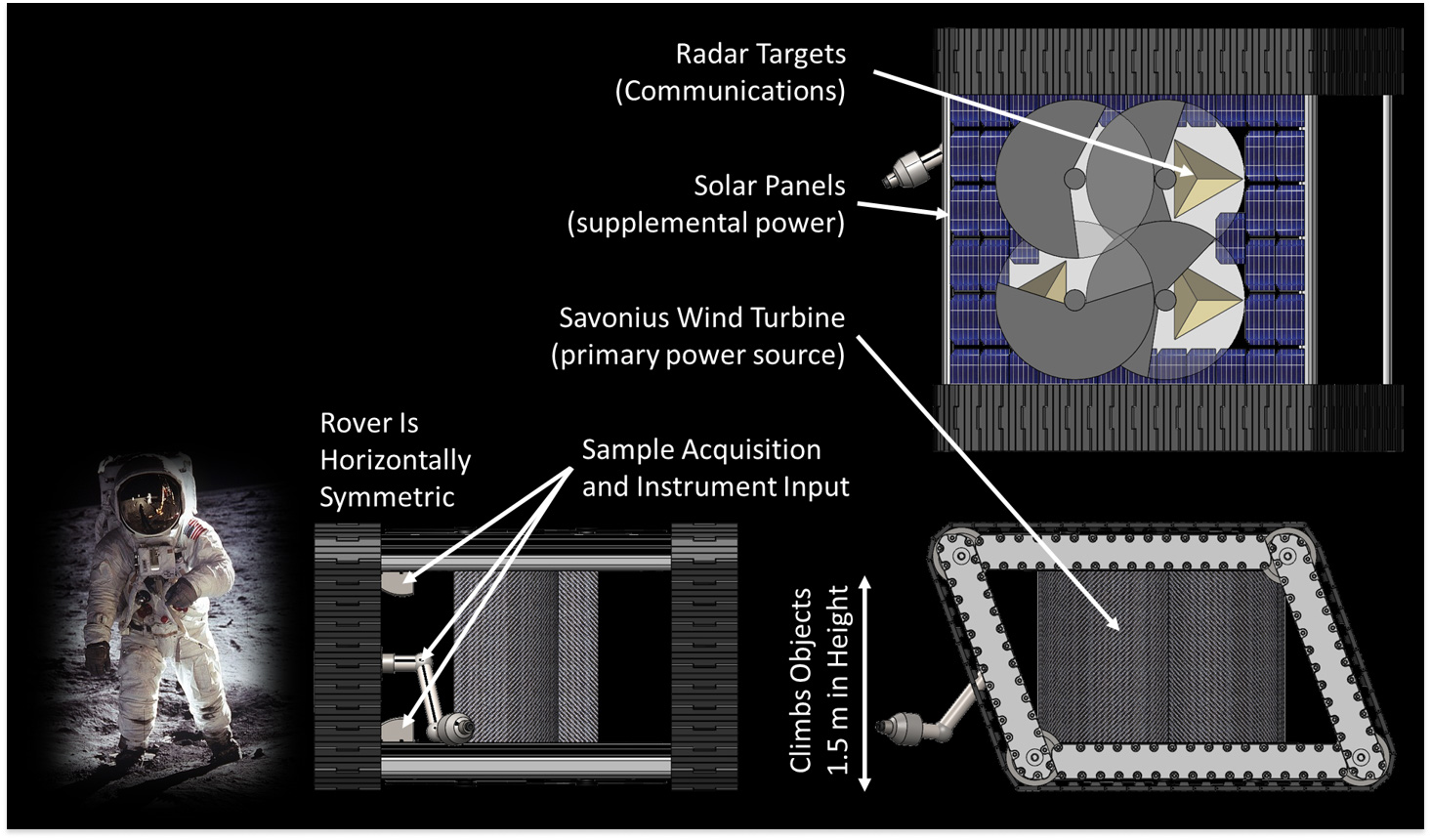

"In Phase 1, purely mechanical rover technologies were compared to a high-temperature electronics rover and hybrid rover technologies," Sauder and his colleagues wrote in a description of the project. "A purely mechanical rover, while feasible, was found to not be practical, and a high-temperature electronics rover is not possible with the current technology, but a hybrid rover is extremely compelling."

This hybrid rover, as currently envisioned, would trundle across Venus not on wheels but on treads, like a tank. Most of its power would be generated by an onboard wind turbine, though roof-mounted solar panels would help as well.

The team's current plans also call for AREE to feature a radar target with a rotating shutter, which would allow the rover to selectively bounce back radar signals from an overhead orbiter. As such, AREE could relay data in an old-fashioned, Morse-code sort of way.

"When you think of something as extreme as Venus, you want to think really out there," JPL engineer Evan Hilgemann, who's working on AREE high-temperature designs, said in the same statement. "It's an environment we don't know much about beyond what we've seen in Soviet-era images."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.