TRAPPIST-1 Planets May Still Be Wet Enough for Life, Despite Losing Many Oceans

When it comes to the seven rocky, roughly Earth-size planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system, the question on everyone's mind is: Could they support the kind of life we find here on Earth?

A new study may add another tick to the "yes, possibly" column.

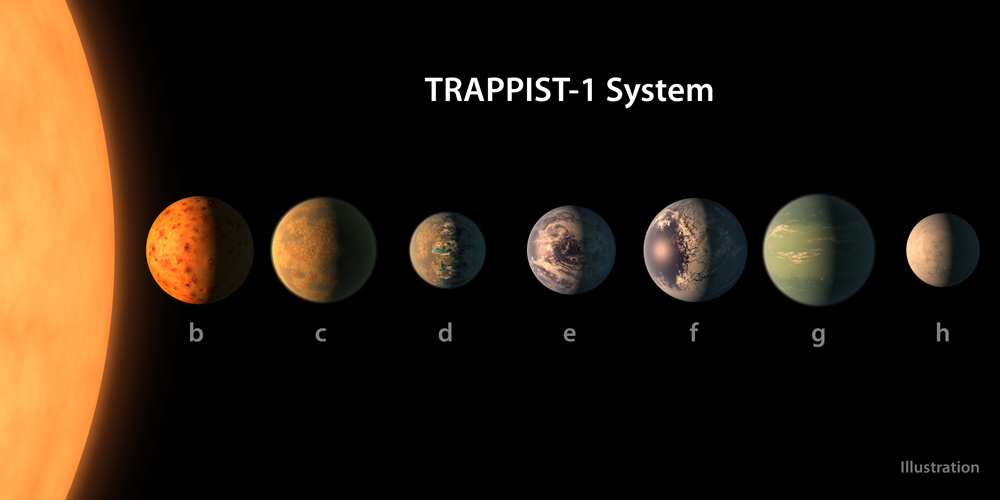

The seven TRAPPIST-1 planets all orbit their parent star closer than Mercury orbits the sun. In Earth's solar system, that position would likely mean certain death for life, but the TRAPPIST-1 star is much dimmer and cooler than our sun, so there is still hope. Three of the TRAPPIST-1 planets appear to orbit at a distance where their surface temperatures could be right for liquid water, also known as the habitable zone. [TRAPPIST-1: How Long Would It Take to Fly to 7-Planet System?]

The new study looks at how much ultraviolet (UV) radiation is received by each of the planets, because this could affect how much water the worlds could sustain over billions of years, according to the study. Lower-energy UV light can break apart water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen atoms on a planet's surface, while higher-energy UV light (along with X-rays from the star) can heat a planet's upper atmosphere and free the separated hydrogen and oxygen atoms into space, according to the study. (It's also possible that the star's radiation destroyed the planets' atmospheres long ago.)

The researchers measured the amount of UV radiation bathing the TRAPPIST-1 planets using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, and in their paper they estimate just how much water each of the worlds could have lost in the 8 billion years since the system formed.

It's possible that the six innermost planets (identified by the letters b, c, d, e, f and g), pelted with the highest levels of UV radiation, could have lost up to 20 Earth-oceans' worth of water, according to the paper. But it's also possible that the outermost four planets (e, f, g and h — the first three of which are in the star's habitable zone) lost less than three Earth-oceans' worth of water.

If the planets had little or no water to start with, the destruction of water molecules by UV radiation could spell the end of the planets' habitability. But it's possible that the planets were initially so rich in liquid water that, even with the water loss caused by UV radiation, they haven't dried up, according to one of the study's authors, Michaël Gillon, an astronomer at the University of Liège in Belgium. Gillon was also lead author on two studies that first identified the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It is very likely that the planets formed much farther away from the star [than they are now] and migrated inwards during the first 10 million years of the system," Gillon told Space.com in an email.

Farther away from their parent star, the planets might have formed in an environment rich in water ice, meaning the planets could have initially had very water-rich compositions.

"We're talking about dozens, and maybe even hundreds of Earth-oceans, so a loss of 20 Earth-oceans wouldn't matter much," Gillon said. "What our results show is that even if the outer planets were initially quite water-poor like the original Earth, they could still have some water on their surfaces."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter