William Shatner Beams a Message to NASA Voyager Probes for 40th Anniversary

In honor of NASA's Voyager 1 probe's 40th anniversary today (Aug. 5), William Shatner helped send a special message to the distant spacecraft, selected by popular vote.

During a news conference on the mission from the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., the action switched for a moment to NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab in California, where Shatner joined the JPL staff to send the one message, out of 30,000 submitted, chosen by popular vote to transmit to the Voyager spacecraft more than 13 billion miles from Earth.

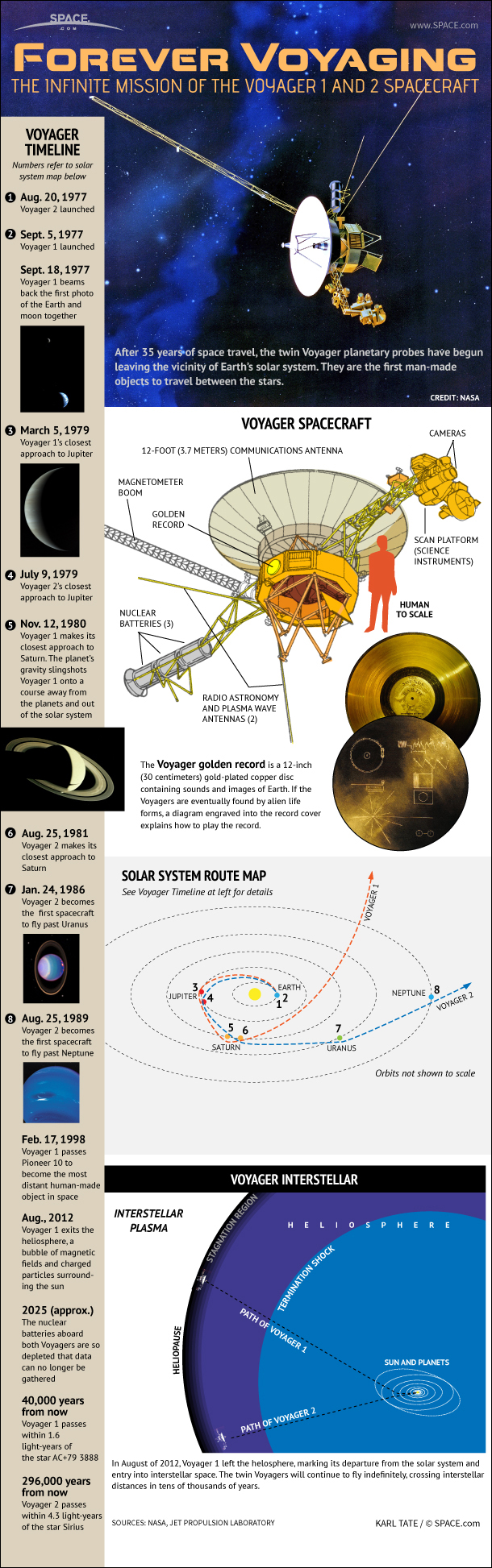

Shatner, famous for playing Captain Kirk in the original "Star Trek" series and movies, opened the envelope to read the message, which was originally submitted on Twitter by Oliver Jenkins: "We offer friendship across the stars. You are not alone." While the message will not be stored in the same way as the probes' famous Golden Record, it will be beamed toward the spacecraft along with its normal instructions and communications.[The Golden Record in Pictures: Voyager's Message to Space Explained]

Shatner then directed JPL engineer Annabel Kennedy to send the message.

"Are the hailing frequencies opened?" Shatner asked.

"They are ready and set to go," Kennedy replied.

Over the course of 28 seconds, the message — no more than 60 characters — was emitted from Deep Space Network antenna DSS63 just outside of Madrid, whose dish stretches three-quarters of the length of a football field. The message will reach the spacecraft after about 19 hours.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Since their launches in 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 have transmitted astounding views of the solar system back to Earth, giving researchers the first close-up looks of Jupiter and Saturn's planetary systems, plus Uranus and Neptune.

"Four decades ago, in 1977, NASA launched the Voyager 1 spacecraft, only a little over eight years after the blast-off to Apollo 11 in 1969," Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's deputy administrator, said from the Smithsonian during the news conference. "In exploration terms, Voyager was and still is, to me and to so many, the Apollo 11 of space science. It's a mission that changed everything.

"It not only changed what we know, but how we think," Zurbuchen added. "It's about exploration of the unknown, and redefining what we can and cannot do as humans."

"From many points of view, Voyager really represents humanity's most ambitious journey of discovery," Voyager principal investigator Ed Stone added. "Voyager began when Gary Flandro discovered that there was a [window] near 1997, plus or minus a year, where a single spacecraft could be launched and could fly by all four giant planets — it was called the 'Grand Tour.' That was in 1965. By 1972, they had been sort of downsized to MJS77, which is Mariner, Jupiter, Saturn, a four year mission just to those two planets and their moons and rings. That, fortunately, was to be launched in 1977, however, so that if they continued to work, they could go on to Uranus and then finally Neptune, which is what Voyager 2 did, completing the grand tour of the outer planets … in 12 years rather than 30 years."

While Voyager 1 gave unprecedented views of the outer gas planets, Voyager 1 veered upward after Jupiter and Saturn and headed for the outer limits of the solar system. [Voyager at 40: 40 Epic Photos from the 'Grand Tour']

Each has redundant systems that has let the spacecraft continue to report back data as they cross through the threshold of interstellar space — Voyager 1 has already gone, and Voyager 2 should reach it soon.

"I'm a cosmic ray physicist, so getting Voyager 1 into interstellar space was the Holy Grail in my area of research," Alan Cummings, a researcher at Caltech who worked on Voyager from the 1970s, said at the conference. Suddenly, the cosmic rays obscured by the sun's steady stream of particles becomes possible to measure.

And researchers are eagerly waiting for Voyager 2 to reach that boundary, too.

"I like to say that the joy of having two, as Alan was saying, you have to have a model that fits both data points," Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at JPL, said during the conference. The researchers said they anticipate Voyager 2 reaching that boundary within the next few years.

Today, Voyager 1 and 2 are "as healthy as senior citizens can be," Dodd said. "Each of them has had different ailments over the years. For example, Voyager 2 is tone-deaf: every time we send a command to the spacecraft we have to put it in two different frequencies in order for the spacecraft to hear it. Voyager 1 does not have an operating plasma science instrument, and what that means is Voyager 1 cannot really directly feel the solar wind and the high-energy charged particles coming from the sun." [Celebrate Voyager Probes' 40th Anniversary with Scientist Stories, Free Posters]

Soon, Dodd said, the researchers will have to decide which instruments to turn off to conserve power from the spacecraft's nuclear generators — some instruments should be running until at least 2025, and maybe longer. "I hope that I can sit here 10 years from now with all these folks and talk about the 50th anniversary of Voyager launch and still have them flying," she added.

Of course, even after NASA loses contact with the Voyager spacecraft, they will continue out into the unknown — and the Golden Records affixed to them are set to last for billions of years, the researchers said. So as NASA sent a message to Voyager, Voyager continues to travel outward, carrying its message to the stars.

"What an honor; I am so pleased to be here," Shatner added from JPL. "It's a magical place, JPL, and this is a magical moment. To send a message to Voyager. And once it reaches Voyager, it keeps going, so it's like an advance man: Voyager coming! Voyager coming! To all the little green people out there."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.