How to See the Sunspot That Fired Off a Monster Solar Flare

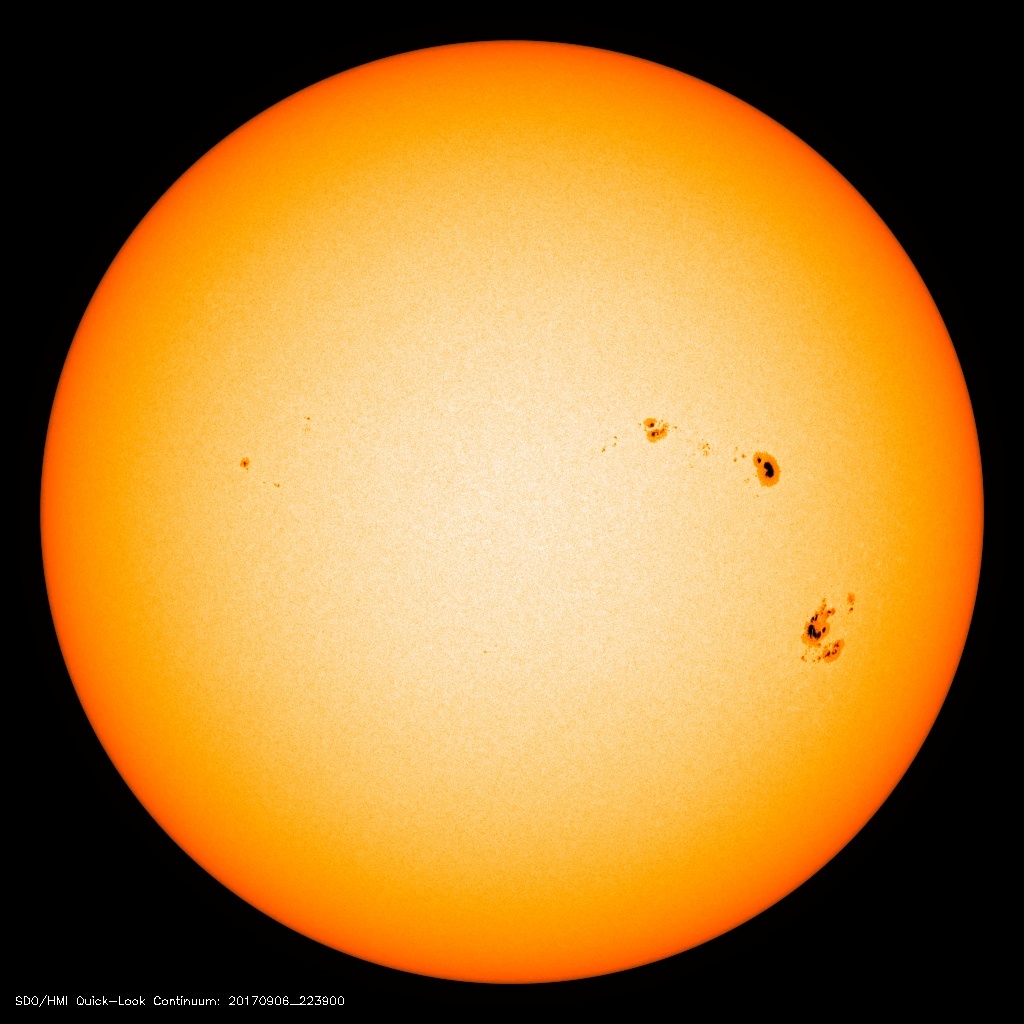

Early Wednesday (Sept. 6), the sun released what appears to be the largest solar flare of the past decade. You can catch a glimpse of the sunspot that is likely responsible for that enormous solar explosion, as long as you still have your solar viewing glasses left over from the Aug. 21 total solar eclipse.

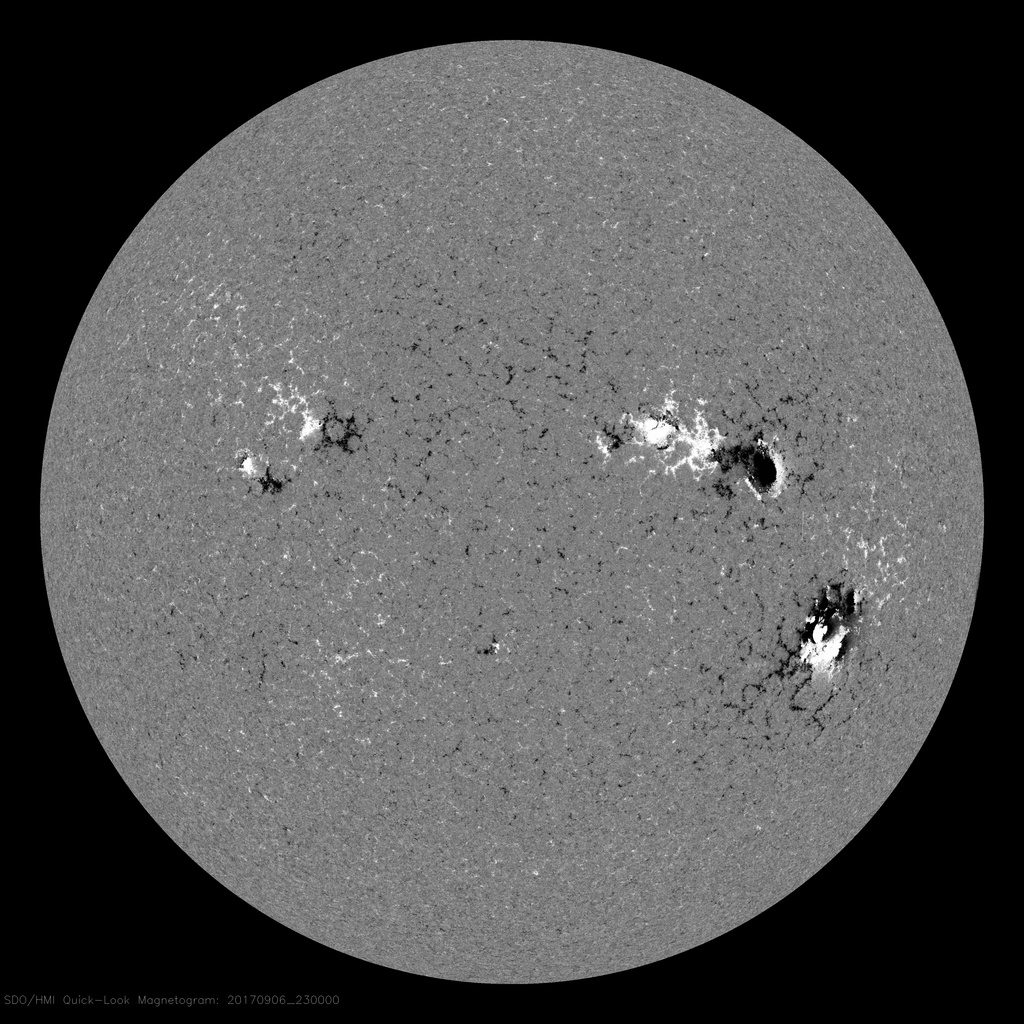

Sunspots are dark and relatively cool regions on the surface of the sun where bundles of magnetic-field lines rise up through the surface. They are associated with solar activity like flares (extremely bright flashes of light) and coronal mass ejections, or CMEs (explosions of charged particles).

Using solar viewing glasses or eclipse-viewing glasses, it's possible to see these dark freckles on the surface of the sun. Right now, there are two fairly large sunspots on the Earth-facing side of our nearest star. Remember to never look directly at the unobscured sun with your naked eyes, and make sure your solar viewing glasses meet the international standard for safety.

"Flares and sunspots go together," Rob Steenburgh, a space scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center, told Space.com in an email.

Powerful flares can cause interruptions in radio transmissions around Earth, Steenburgh said. They can also pummel satellites with potentially damaging particles, but CMEs are even more threatening to humans. The explosions of charged particles can damage satellite electronics and, in some cases, even send currents surging through power grids on the ground, potentially causing blackouts. These are some of the major reasons why scientists monitor the sun and try to anticipate when these events will occur.

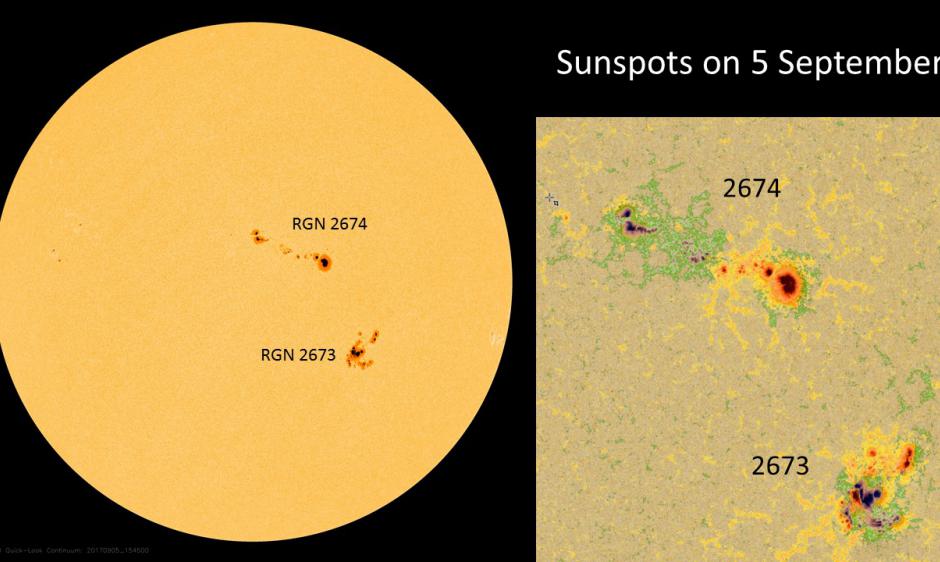

"Forecasters evaluate the size and magnetic complexity of the active regions (groups of related [sun]spots) to determine their potential for flare production," Steenburgh said. "Generally speaking, the larger and more complex the active region, the greater the potential for significant flares."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Karl Battams, an astrophysicist and computational scientist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), said in a tweet that the smaller of the two sunspots is responsible for the massive flare recorded yesterday (Sept. 6).

The sun is currently approaching a solar minimum, meaning a time of reduced solar activity. During solar minimums, there are fewer sunspots, and fewer events like flares and coronal mass ejections. The sun cycles between a solar minimum and a solar maximum over the course of an 11-year solar cycle.

"Even though we're approaching solar minimum, there can still be large regions and events like this," Steenburgh said. "They're less frequent/common, but no less impressive."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter