Hurricane Watch: How Satellites Track Huge Storms from Space

Sophisticated satellites are helping scientists monitor the volatility of Hurricanes Irma, Katia and Jose in the Atlantic basin. As the spacecraft capture data on the massive storms, weather agencies can merge the different observations to create accurate forecasts about where the hurricanes are traveling, the strength of their winds and which communities should start emergency preparations.

NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) developed satellites through NASA's Earth Observing System (EOS) to carry instruments into low-Earth orbit that can make nuanced detections of rainfall, cloud formations and the microphysics of these hurricanes.

Some satellites, such as the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory, collect data on their own. In several instances, satellites operate collectively as a group — known as a constellation — to create a precise composite understanding of storms. One example is the new Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS), which launched in December 2016 for hurricane tracking. [See Hurricane Irma in Motion in These NASA and NOAA Gifs]

The Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) system built and developed the satellites comprising GOES as part of the agency's collaboration with NOAA. NASA continues to build newer GOES spacecraft to help NOAA collect increasingly reliable weather forecasts and seasonal predictions. The satellites can observe various details about a hurricane by watching how heat and light radiate from the stormy area.

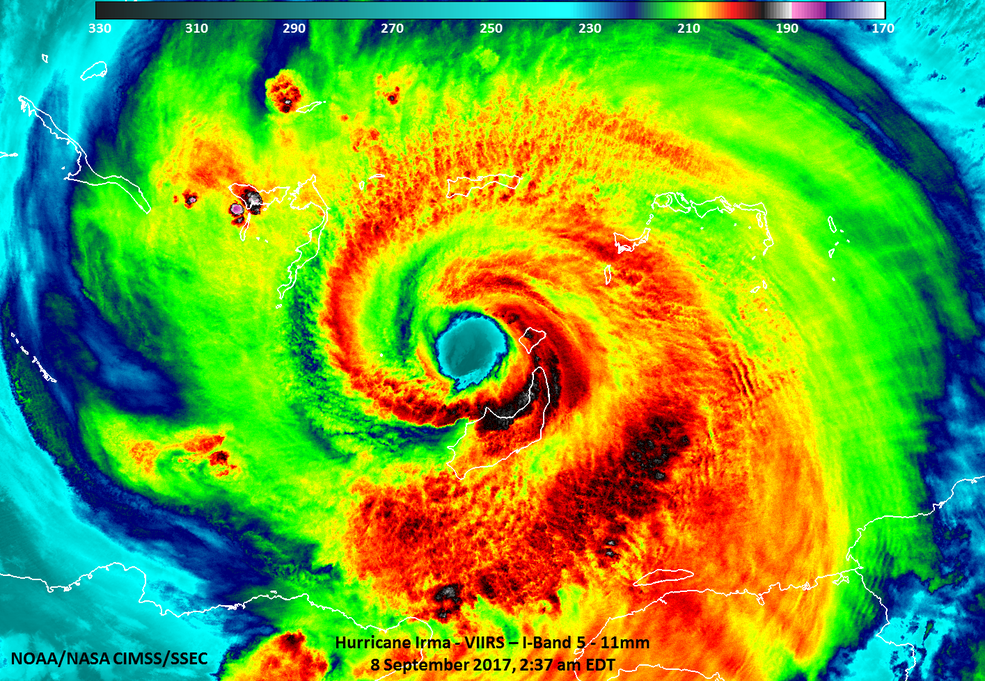

Infrared channels on the GOES satellites can detect the presence of tall vertical clouds in the storm, because the infrared channels sense heat radiation and clouds absorb and re-emit the sun's heat differently than non-stormy patches on Earth's surface do, according to NOAA. The taller the cloud, the greater its activity will likely be, and to demonstrate this, infrared images are usually colored to indicate regions where clouds could be most tempestuous.

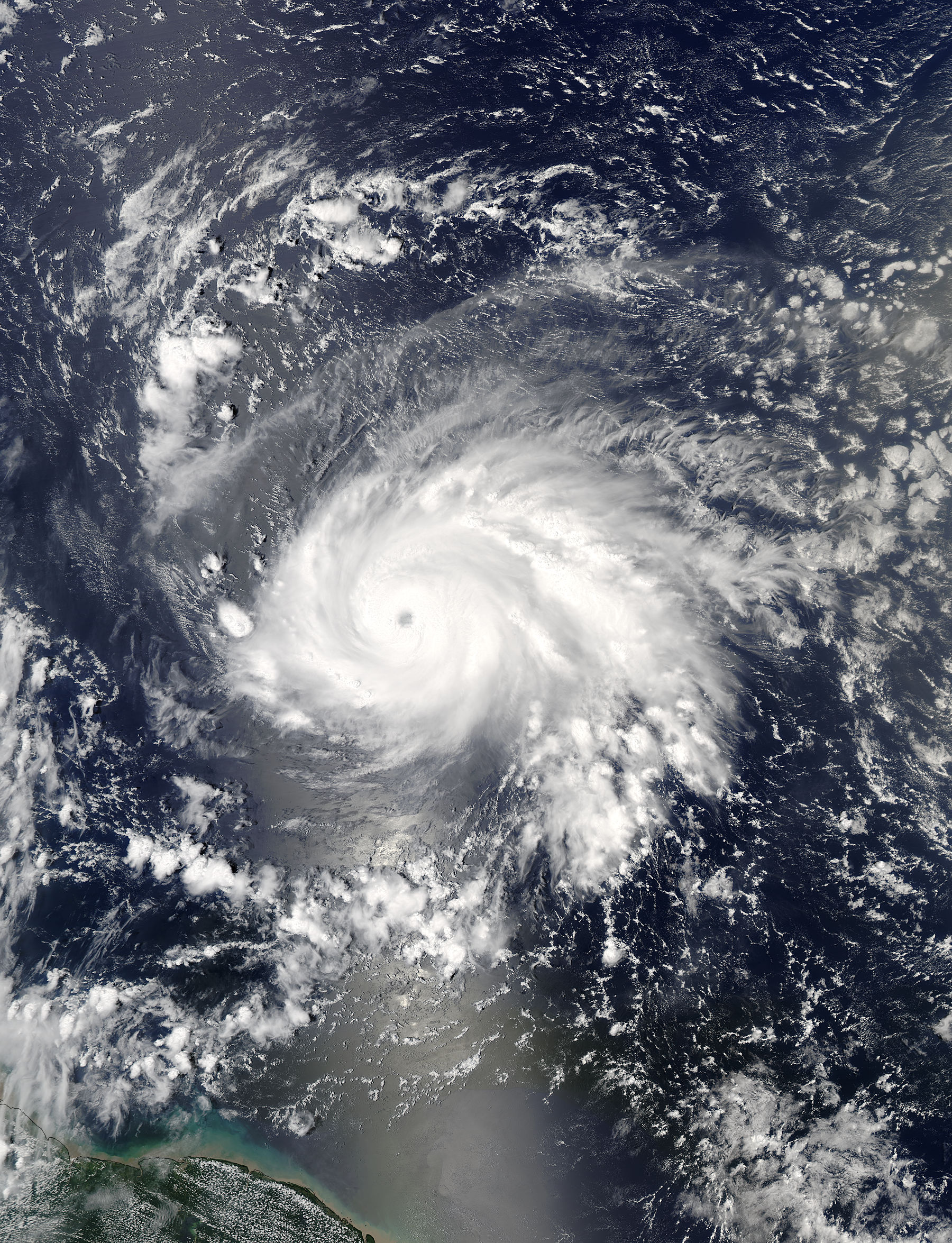

The GOES satellites also have visible-light channels, which are limited at the night when the sun is not illuminating the hurricane, but have the benefit of taking higher-resolution imagery.

NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) collaborate on the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) mission, which uses a satellite called the GPM Core Observatory. On board this satellite are two instruments — the GPM Microwave Imager and Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) — which the satellite uses to assess rainfall. GPM scientists work in unison with NOAA and international atmospheric agencies to measure the specific characteristics of hurricane precipitation to better understand Earth's water and energy cycle. Other agencies participating in this work include the Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES) in France, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) and the European Organization for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

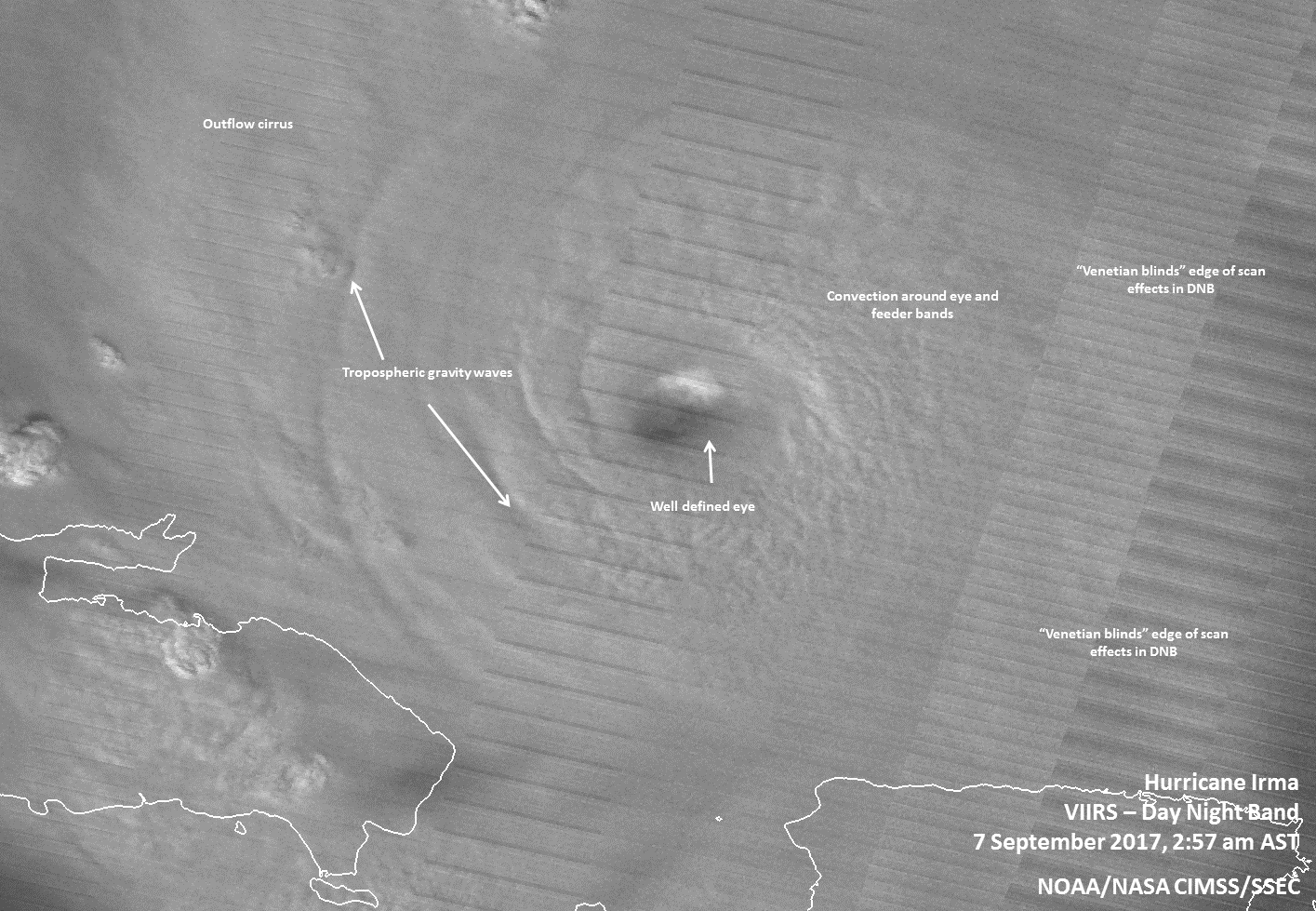

NASA and NOAA also partnered to develop the Joint Polar Satellite System, which created the primary satellite for NOAA's weather observations, the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite. According to NOAA, the spacecraft circles Earth 14 times a day to provide full observations and weather predictions for the United States. The newest satellite in this program, JPSS-1, arrived in early September to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California and is currently being prepared for a November launch to accompany Suomi NPP in that satellite's observations. [Space Station Crew Sees Hurricane Irma's Power from Orbit (Photos, Video)]

Satellites small enough to sit on your desk could be the next line of hurricane-observation technology. Just recently, in May 2017, the hurricane-tracking CYGNSS constellation moved into its science-operations phase, NASA officials said in a statement. CYGNSS will accomplish what up until now has been impossible: probing the eye and surrounding inner core of a hurricane from space. Using GPS signals, CYGNSS can penetrate a storm's intense precipitation to get a good look at the eye wall.

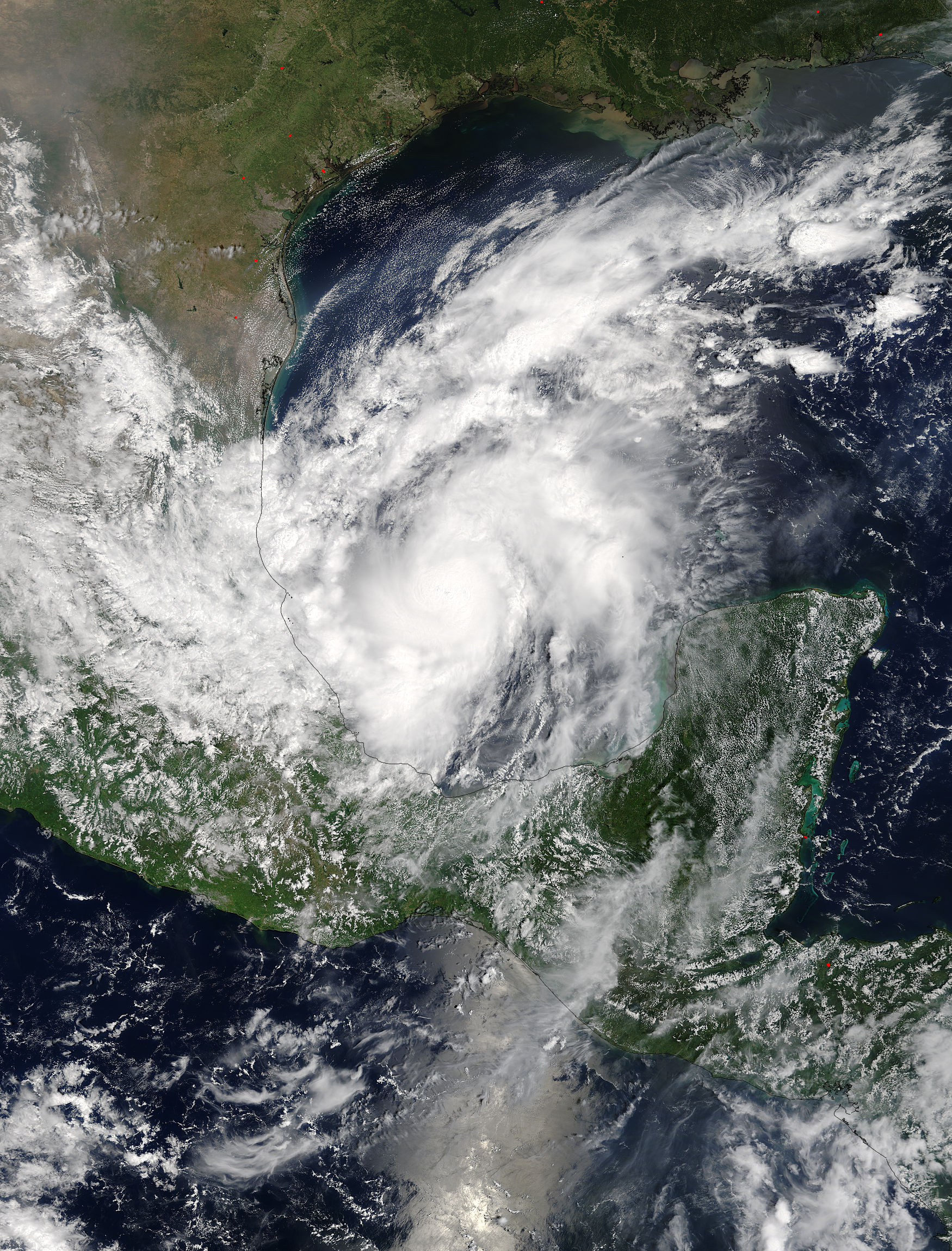

NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites work by alternating within timed orbits, so that Terra (originally known as EOS AM-1) passes from north to south over the equator in the morning, while Aqua (originally known as EOS PM-1) passes south to north over of the equator in the afternoon. Using their key instrument, MODIS, or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, the satellites pick up data in 36 spectral bands, or wavelengths, as the two satellites view the entire Earth's surface every one to two days.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.