Rings Revealed: How Cassini's Saturn Odyssey Exceeds Expectations

After 14 years of exploration, the Cassini spacecraft is preparing to write its final chapter on the Saturn system.

No other spacecraft in history has come to know a single planetary system as intimately as Cassini knows Saturn: Cassini is the first spacecraft to visit Saturn up close since the Voyager probes flew by in 1980 and 1981, and the mission has given scientists their best-ever views of the gas giant.

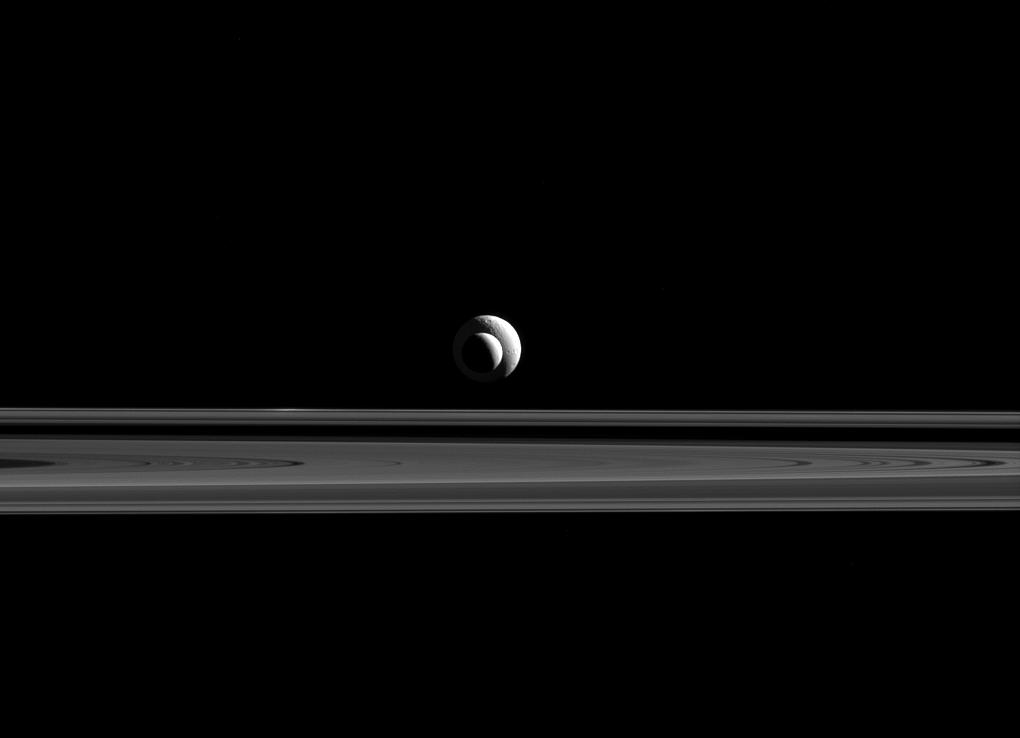

The probe has spent more than a decade observing Saturn, studying storms in its cloud tops, learning about its strange, striped atmosphere, probing its cloaked interior and zipping through its more than 60 moons and a ring system stretching more than eight times the planet's radius.

"The mission has exceeded all of our expectations, done better than we could have ever dreamed," Curt Niebur, Cassini's program scientist from NASA headquarters in Houston, said during a press teleconference in August. "The Saturn system is absolutely chock-full of amazing worlds of all sizes, and Cassini has been exploring them for the past 13 years. [Saturn's In Photos: The Strangest Moons of Saturn Seen by Casssini]

"Since our arrival in 2004, we've watched the seasons change on Saturn, which is just an incredible opportunity, considering a year on Saturn lasts 29 Earth years," he added. "We've watched the particles and the rings around Saturn collide and glide during their gravitational dance, and we've confirmed things that we suspected might exist in the Saturn system, but even more pleasantly, we've been shocked by things that we never predicted we would find."

Cassini's scientists have watched a Saturn storm erupt and run over its own tail after circling the entire planet. They've probed the mysteries of the Earth-size, hexagonal jet stream on the planet's pole that persists in all seasons, but changes color over time. Researchers have sent a probe down to Saturn's largest moon, Titan, to see the lakes, seas and rivers of methane on its surface, and have flown Cassini through the geyser jets of the tiny moon Enceladus to probe its newfound ice-covered ocean.

"These two new worlds, Titan and Enceladus, which were so completely revealed to us by Cassini, have changed the idea that ocean worlds like Earth and [Jupiter's moon] Europa are rare in the universe," Niebur said. "And this in turn is changing our views about finding [habitable worlds] and about how prevalent and common habitable environments and even life beyond Earth might truly be."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission has continually adapted to the mysteries it uncovered in Saturn's system. The probe used flybys of Titan to adjust its orbit and perform 162 targeted flybys of Saturn's many moons, including 127 of Titan itself. [No Turning Back: Titan Flyby Assures Cassini's Crash into Saturn]

"Cassini's had a long-distance, you might say, long-term relationship with Titan," Earl Maize, Cassini's project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said during the teleconference. "[During] each of these flybys, Titan has shared some of its secrets with us, and at the same time shaped Cassini's trajectory."

Via an international collaboration, Cassini brought Europe's Huygens lander to the Saturn system and dropped it down on Titan, giving Earthlings a stunning view of the moon's liquid oceans and complex organic atmosphere. Maize said that moment is his pick for the most amazing part of the Cassini mission.

"The collaboration … between three space agencies and all these thousands of people on the ground … [to] put a probe onto Titan, capture signal on the way down, land it softly on the surface and play those images back — I still give myself goose bumps just seeing that first image," Maize said. The Cassini mission is a cooperative project between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Italian Space Agency.

For Linda Spilker, a Cassini project scientist at JPL, the probe's investigation of the tiny moon Enceladus was the most exciting part of the mission.

"To actually see this plume of water vapor and waterized particles coming out of the south pole of a moon that's only 300 miles [480 kilometers] across was absolutely astonishing," Spilker said at the teleconference. "And then to take instruments built for other purposes and turn them toward sampling and flying through the plumes and actually measuring the constituents — finding a salty global ocean containing organics, the possibility of hydrothermal vents and just revealing a world that we thought was completely frozen solid when we first got to Saturn."

"Enceladus has no business existing," Niebur added, "and yet there it is — practically screaming at us, 'Look at me! I completely invalidate all of your assumptions about the solar system!'"

To protect those Enceladus and Titan from contamination with Earth life, Cassini is going to dive down into Saturn's atmosphere before the probe runs out of fuel, which could have left it drifting on a collision course with the planet's moons. Although the Huygens mission met planetary-protection requirements back in 2005, when it landed on Titan, scientists' new information about that moon's potential habitability has made researchers keen to protect it from further exposure, Cassini research scientists have said. Saturn's "Grand Finale" dive is primarily aimed to protect Enceladus, which has a higher planetary-protection standard — Titan is just a bonus, the scientists said.

For the final dive, researchers will turn their focus back to the planet itself and its rings for a dramatic, fact-finding atmospheric crash.

"The mission has been insanely, wildly, beautifully successful," Niebur said. "But Cassini will not go quietly."

The spacecraft's Grand Finale orbits have brought it closer to the gas giant than any spacecraft has traveled, traversing the gap between the planet and its rings and diving into the unknown to learn as much as possible about the planet.

"Some of our key science goals during the Grand Finale are trying to understand Saturn from the inside out, to figure out the length of a Saturn day and to determine the mass of the rings and the composition of Saturn's atmosphere," Spilker said. "Our understanding of this fascinating new data is still evolving for me and the science team. There are so many puzzles at Saturn.

"Scientists love mysteries, and the Grand Finale is providing mysteries for everyone," she added. And surely that will continue with its final dive, she said.

At the briefing, researchers described how the probe would eventually stop sending photos, but would be sending back data gathered with its instruments right up until the end. The probe's first protective blankets will burn off first as it pierced the planet's upper atmosphere — "just like you see when you re-enter the atmosphere on Earth," Julie Webster, a Cassini operations manager at JPL, said at the conference — and then the craft will reach the aluminum melting point within about 20 seconds. The probe's iridium will be the last to melt, occurring about 30 seconds after the aluminum; everything will be melted away within a minute.

While ground-based observers will be watching the spacecraft's demise, the researchers said, it will occur on the planet's dayside during local noon, so it's unlikely to cause any visible disturbance. Despite this, the final data Cassini sends will give researchers an unprecedented view of the planet's composition, the researchers said.

"I feel a tremendous sense of pride in all that Cassini has accomplished," Spilker said. "In so many ways, we've really rewritten the textbooks on the Saturn system — literally. We have new books coming out about Saturn, the rings, the magnetosphere, so many new things Cassini has discovered.

"It's time to take our knowledge and information and then move that out into future missions, to the outer planets and beyond," she added.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.