There Is Boron on Mars — Another Sign the Red Planet Could Have Hosted Life

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has discovered boron in Gale Crater — new evidence that the Red Planet may have been able to support life on its surface in the ancient past.

Boron is a very interesting element to astrobiologists; on Earth, it's thought to stabilize the sugary molecule ribose. Ribose is a key component of ribonucleic acid (RNA), a molecule that's present in all living cells and drives metabolic processes. But ribose is notoriously unstable, and to form RNA, it is thought that boron is required to stabilize it. When dissolved in water, boron becomes borate, which, in turn, reacts with ribose, making RNA possible. [Boron Found on Mars for First Time By Curiosity (Video)]

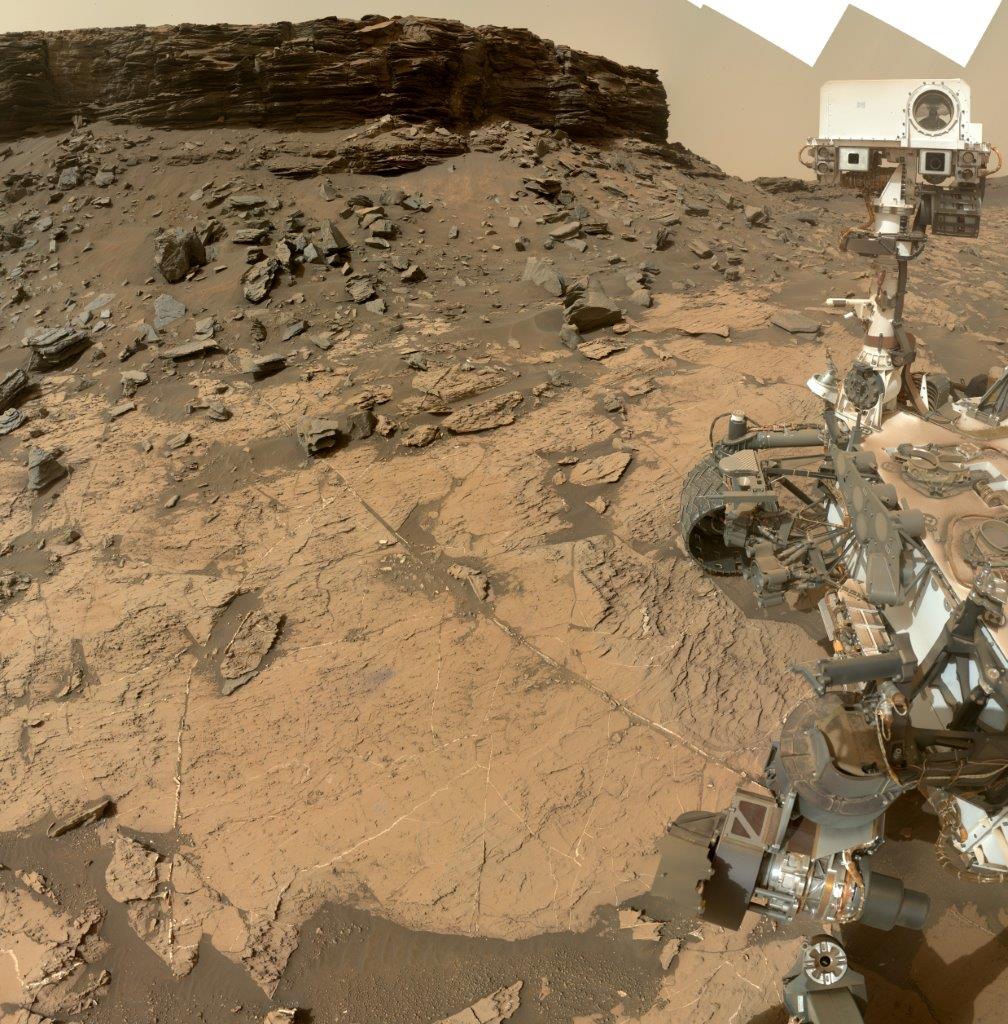

In a new study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers analyzed data gathered by Curiosity's ChemCam (Chemistry and Camera) instrument, which zaps rocks with a powerful laser to see what minerals they contain. ChemCam detected the chemical fingerprint of boron in calcium-sulfate mineral veins that have been found zigzagging their way through bedrock in Gale Crater, the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) crater that the rover is exploring. These veins were formed by the presence of ancient groundwater, meaning the water contained borate.

The find raises exciting possibilities, the researchers said.

"Because borates may play an important role in making RNA — one of the building blocks of life — finding boron on Mars further opens the possibility that life could have once arisen on the planet," study lead author Patrick Gasda, a postdoctoral researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, said in a statement.

"Borates are one possible bridge from simple organic molecules to RNA," he added. "Without RNA, you have no life. The presence of boron tells us that, if organics were present on Mars, these chemical reactions could have occurred."

Scientists have long hypothesized that the earliest "proto-life" on Earth emerged from an "RNA World," where individual RNA strands containing genetic information had the ability to copy themselves. The replication of information is one of the key requirements for basic lifelike systems. Therefore, the detection of boron on Mars, locked in calcium-sulfate veins that we know were deposited by ancient water, shows that borates were present in water "0 to 60 degrees Celsius (32 to 140 degrees Fahrenheit) and with neutral-to-alkaline pH," the researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We detected borates in a crater on Mars that's 3.8 billion years old, younger than the likely formation of life on Earth," Gasda added. "Essentially, this tells us that the conditions from which life could have potentially grown may have existed on ancient Mars, independent from Earth."

Since landing on Mars in 2012, Curiosity has uncovered compelling evidence that the planet used to be a far wetter place than it is now. For example, the rover has found evidence of a lake-and-stream system inside Gale Crater that lasted for long stretches in the distant past. And, by climbing the slopes of Mount Sharp — the 3.4-mile-high (5.5 km) mountain in the crater's center — Curiosity has been able to examine various layers of sedimentary minerals that formed in the presence of ancient water.

These studies are helping scientists gain a better understanding of how long these minerals were dissolved in the water, where they were deposited and, ultimately, how they impacted the habitability of the Red Planet. The detection of boron is another strand of evidence supporting the idea that ancient life might have existed on our neighboring planet.

Follow Ian O'Neill on Twitter @astroengine and at Astroengine.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.