The End Is Nigh for Cassini: Saturn Probe Enters Final 48 Hours

PASADENA, Calif. — The end is nigh for NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which is now less than 48 hours away from its scheduled death dive into Saturn.

At NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in southern California, mission scientists are now preparing to receive Cassini's final data transmissions early Friday morning (Sept. 15). Heat and friction created by the fall will cause Cassini to break apart, and its components to vaporize, only 2 or 3 minutes after it enters Saturn's atmosphere.

"What's going to happen on Friday is absolutely inevitable," Earl Maize, project manager for Cassini, said during a news conference at JPL today (Sept. 13). The Cassini mission is operated out of JPL using the Deep Space Network, a series of telescopes around the globe that communicate with spacecraft beyond Earth and the moon. [Cassini's Saturn Crash 2017: How to Watch Its 'Grand Finale']

Cassini's fate was sealed back in April, when the mission team used the gravity of Titan to put the probe on a flight path that looped it between Saturn and its innermost rings. On Monday (Sept. 11), another distant flyby with Titan slowed down the Cassini probe so that it will be moving slightly more slowly during its next close pass with the planet, causing it to dip deeper into the planet's atmosphere. The probe will be destroyed by the atmospheric encounter before it can escape back into orbit.

At about 6:50 a.m.PDT this morning (9:50 a.m. EDT/1350 GMT), Cassini turned its antenna away from Earth and began taking its last images of the Saturn system, adding to a collection of more than 450,000 images gathered throughout the life of the spacecraft. The probe will complete that task at about 12:58 p.m. PDT (3:58 p.m. EDT/1958 GMT) tomorrow (Sept. 14).

At 2:45 p.m. PDT (5:45 p.m. EDT/2145 GMT) on Thursday, Cassini will begin transmitting all of the information currently stored on its data recorder back to Earth. That data dump is expected to be complete by about 8:00 p.m. PDT (11 p.m. EDT/0300 GMT on Sept. 15), at which time NASA will release Cassini's final images to the public. [Cassini's 13 Greatest Saturn Discoveries]

At 1:37 a.m. PDT (4:37 a.m. EDT/0837 GMT) on Sept. 15, the Cassini team will reconfigure the spacecraft so that it can instantly transmit data directly back to Earth during its dive into Saturn's atmosphere. In its normal configuration, the probe captured data, stored it and transmitted it back to Earth during scheduled data dumps. The probe will not have a high enough data transmission rate to send relatively large image files, so it will only transmit data from eight of the probe's 13 instruments.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini will begin its descent through the atmosphere at 4:55 a.m. PDT (7:55 a.m. and EDT 1155 GMT). The probe is expected to transmit data about the planet's atmosphere for about 1 to 2 minutes and is expected to be completely destroyed about 1 minute later.

The life of Cassini

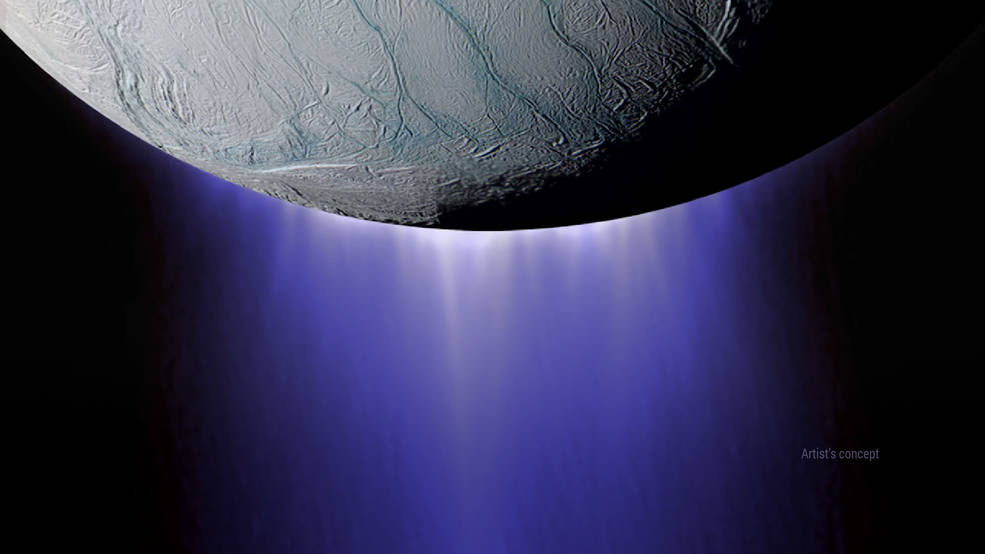

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort between NASA and the European Space Agency — launched toward Saturn in October 1997 and arrived in July 2004. The Huygens lander plopped down on the surface of Saturn's moon Titan shortly after arriving in the Saturn system, while Cassini continued to loop around the ringed planet, its rings and its moons, sending back breathtaking images and incredible data. In conjunction with the data from the Huygens lander, Cassini probed the weird world of Titan and flew through geysers erupting from the surface of the moon Enceladus. Its list of accomplishments goes on and on.

"Not only do we have an environment [at Saturn] that is just overwhelming in its abundance of scientific mysteries and puzzles, we got a spacecraft and a team that could exploit it," Maize said. "It's just been an amazing, amazing mission."

In November 2016, Cassini began a series of maneuvers that sent it hurtling through Saturn's rings. In April, it began a series of maneuvers known as the "Grand Finale," that would ultimately send the probe crashing into Saturn. The spacecraft is running out of fuel, so the mission's end was inevitable. By diving into the planet, Cassini will get the first-ever, in situ data from Saturn's atmosphere.

Cassini's crash into Saturn will also protect moons like Titan and Enceladus, which researchers think could possess environments fit to host life. If Cassini is carrying any bacteria or tiny life forms from Earth, they could invade and contaminate those environments. While the odds of that happening might be slim, the results would be devastating, and could make it impossible for scientists to identify any alien life-forms that might live on those moons.

'We've had an incredible 13-year journey around Saturn, and [Cassini has been] returning data like a giant fire hose. Just flooding us with data," Linda Spilker, the project scientist for Cassini, said at the news conference. "If you imagine all that data as [a] million-piece puzzle, Cassini has been slowly putting together pieces. We have some of the border, some of the regions, and we're trying to put together the picture of the Saturn system."

Already, Cassini scientists say the data returned from those orbits have revealed a more complex mixing between Saturn's atmosphere and its rings than had been predicted. The probe observed a phenomenon called "ring rain" — water vapor and water ice grains falling from the ring system onto the planet — but the scientists at the news conference said the probe observed other chemicals in the ring rain as well.

"There have been lots of surprises," Spilker said. "A lot of the things we thought we knew about Saturn are more complicated than we originally had imagined."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter