Cassini's Swan Song: How Saturn Probe Will Spend Its Final Day

NASA's Cassini spacecraft will work hard to the very end.

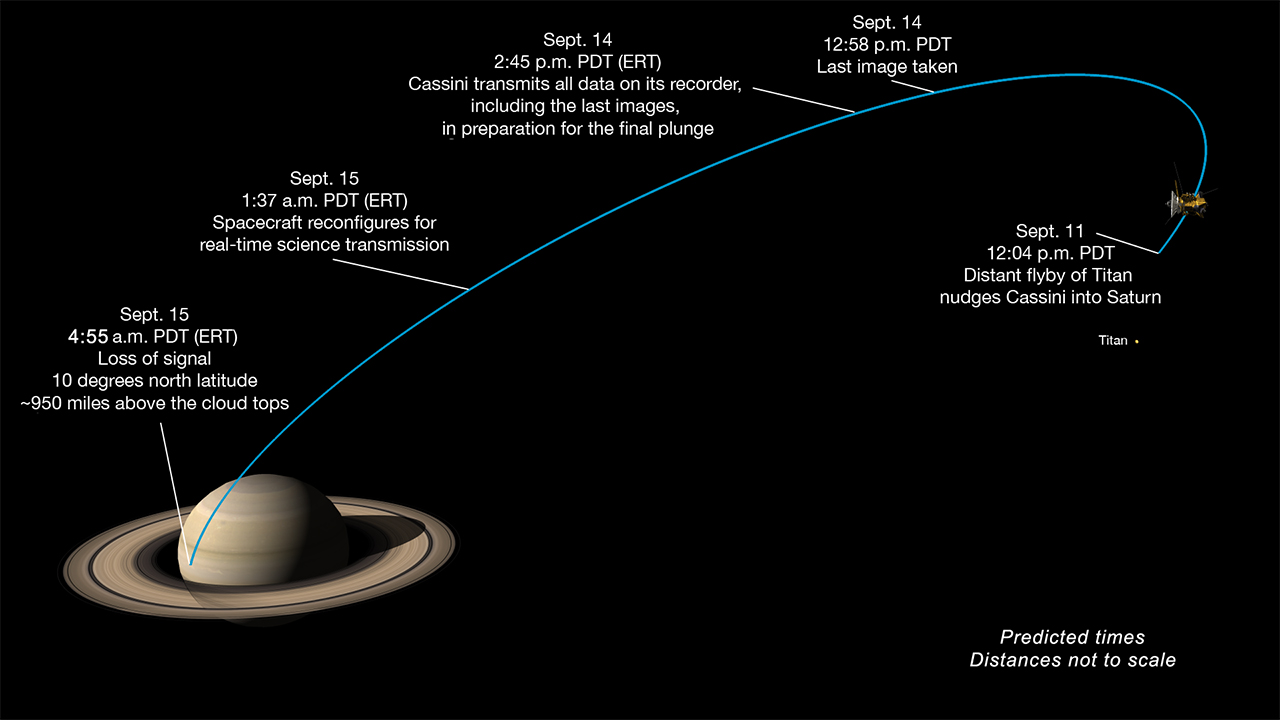

Cassini will plummet into Saturn's atmosphere early Friday morning (Sept. 15), ending its epic 13-year stint at the ringed planet with a bang. But before that happens, the probe will snap its dying image — a photograph of the precise spot where Cassini will meet its fate — send home any stored data remaining in its memory, rotate its science instruments toward Saturn's onrushing air and its antenna toward Earth, and begin streaming real-time data back home.

Cassini's final chapter began with its last Titan flyby, on Monday (Sept. 11), which gave the probe the nudge it needed to head toward Saturn. [Cassini's Saturn Crash 2017: How to Watch Its 'Grand Finale']

"The Titan flyby was just close enough and just the right orientation to seal Cassini's fate," Cassini program manager Earl Maize, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference Wednesday (Sept. 13).

Following the plan

Cassini is being driven into Saturn's atmosphere to ensure that the probe doesn't contaminate the moons Titan and Enceladus — both of which may be capable of supporting life — with microbes from Earth. The spacecraft is nearly out of fuel, so mission managers wanted to dispose of Cassini safely while they still had control of it.

While the bulk of the commands for Cassini's final hours were sent 10 weeks ago, a few last-minute tweaks were uploaded on Wednesday at 6:53 a.m. EDT (1053 GMT; 3:53 a.m. PDT), JPL's Michael Staab told Space.com. As "Cassini Ace," or person on point, Staab is one of the engineers who monitor and communicate with the spacecraft from the mission control room at JPL.

Today (Sept. 14) at 3:58 p.m. EDT (1958 GMT; 12:58 p.m. PDT), Cassini will snap its final photo, targeting the patch of atmosphere where it will meet its fiery fate. (Cassini won't be taking photos during the actual death dive on Friday; information will be at a premium, and images would hog too much bandwidth, mission team members said.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After taking that picture, the probe will slowly rotate, aiming its Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) instrument toward Saturn and the antenna on its tail toward Earth.

If all goes well, Cassini will soon begin sending home the last of the information stored in its memory — a lengthy process that will begin at 5:45 p.m. EDT (2145 GMT; 2:45 p.m. PDT) today and end at 4:37 a.m. EDT (0837 GMT; 1:37 a.m. PDT) Friday morning.

"We will then reconfigure Cassini for its final transmissions," Maize said.

With its solid-state data recorder empty, Cassini will shift into what Maize called "bent-pipe" mode — all of the data flowing into the orbiter will be relayed to Earth almost immediately.

"It's essentially now a real-time instrument," Maize said. (It will still take each "packet" of transmitted data about 1 hour and 23 minutes to travel from Saturn to Earth, however.)

With INMS leading, Cassini will pierce Saturn's atmosphere, an area the spacecraft wasn't originally designed to explore.

"Cassini is not built for the atmosphere," Maize said. "We're a deep-vacuum kind of probe."

Though the spacecraft has skimmed the surface of Titan's thick atmosphere and made a few dips into Saturn's atmosphere on its last five orbits, Cassini's thrusters weren't made for the heavy drag it will encounter on the planet, Maize said.

"The thrusters will be fighting extremely hard to keep the antenna pointed at Earth," he said. "It's going to do that for as long as it possibly can."

As it dives — transitioning from a Saturn orbiter to the very first Saturn atmosphere probe — Cassini will beam home information, which will be received by the ground stations of NASA's Deep Space Network. Most of this data will arrive in Australia, though some will come in through the DSN antenna in Spain. [NASA's Deep Space Network: 50 years of Interplanetary WiFi (Video)]

Cassini's foray into the atmosphere will be very short-lived.

"Cassini will be vaporized in maybe two minutes," Maize said.

Atmospheric models suggest that the spacecraft's last signal will be received back on Earth at 7:55:06 a.m. EDT (1155:06 GMT; 4:55:06 a.m. PDT). Most likely, that final signal will be data-only, Staab said.

"It won't know that something bad has happened to it until it's already over," he said.

But Staab added that it's possible that, in its final moments, the spacecraft will send out a distress message as it tumbles through the atmosphere. Not knowing that its death has been carefully scripted, Cassini may try to alert mission control that something has gone horribly wrong.

Mission controllers wouldn't be able to respond to that putative signal in any meaningful way even if they wanted to; Cassini will die nearly an hour and a half before such a signal reaches our planet.

"You can't intervene on a spacecraft that doesn't exist anymore," Staab said.

Planning for possible problems

Cassini is firmly set on its crash course into Saturn, so it shouldn't need any help reaching its final destination. But that doesn't mean nothing can go wrong.

According to Cassini sequence planner Jan Berkeley, a single poorly placed event in space could cause a problem. For instance, a cosmic ray flung from the depths of space could impact the flight hardware, causing the system to go into safe mode and no longer transmit toward Earth. Berkeley and her team have spent the past few weeks programming solutions to prevent such possible problems.

"We have a whole set of commands that we have ready to go," Berkeley said.

According to Staab, the commands — if needed — would be sent to the flight operations server before being transmitted to the Cassini station at mission control. The acting Ace would then send them on to the spacecraft.

The engineers would work hard to get the spacecraft back on its feet, but Staab said the process would take 10 to 12 hours. "You're racing against the clock at that point," he said.

Once Cassini came back online, Staab said, the data could stream alongside the real-time observations, though the process would consume more bandwidth.

Still, he expressed confidence that the mission would ride through its final hours without a problem, thanks to the Cassini team's preparation.

"You plan for the worst but expect the best," he said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd