With NASA's Cassini spacecraft now just a blur of molecules in Saturn's cloud tops, another gas giant is rotating into the crosshairs of the planetary exploration community.

Cassini plunged intentionally to its death Friday (Sept. 15), bringing an end to 13 years of exploration that revolutionized researchers' understanding of the Saturn system and its ability to host life. But NASA still has a probe investigating a giant planet. That spacecraft, called Juno, has been orbiting Jupiter since last summer.

And two more Jupiter missions are scheduled to launch five years from now: NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will study the possibly habitable Jovian moon Europa; and the European Space Agency's (ESA) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which will investigate the giant planet and three of its four biggest moons (including Europa). [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

Juno

The $1.1 billion Juno mission launched in August 2011 and entered orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

That orbit is a highly elliptical 53-Earth-day-long path that brings the solar-powered Juno within just a few thousand miles of Jupiter's cloud tops at its closest approach. (The original plan called for Juno to shift to a 14-Earth-day orbit last October, but an engine-valve issue nixed that idea.)

During these superclose passes, Juno's instruments gather data about the structure and composition of Jupiter's atmosphere, as well as the planet's gravity and magnetic fields. Such information should end up revealing a great deal about the planet's formation and evolution, mission scientists have said.

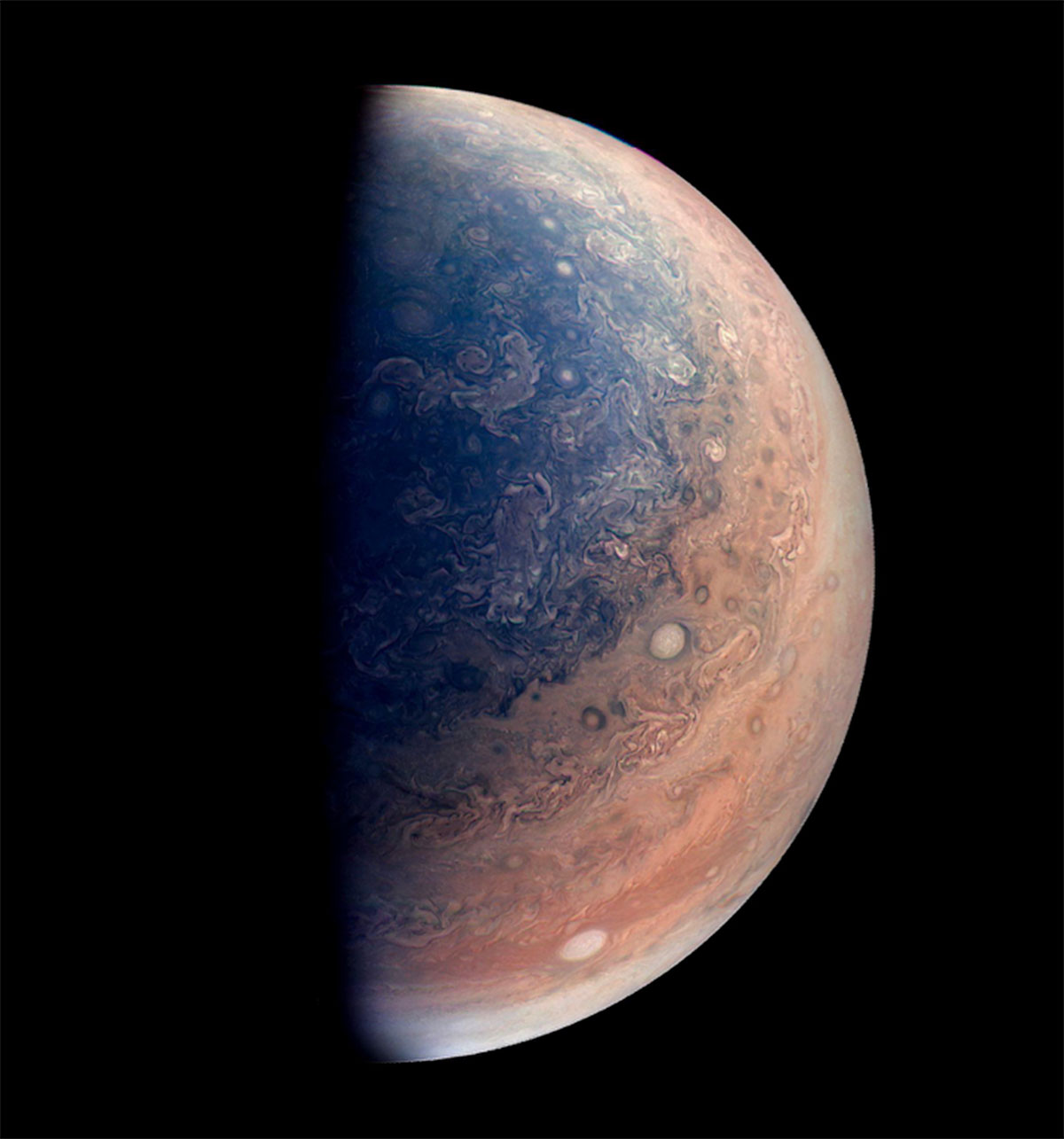

Juno also takes photos — spectacular ones — using its JunoCam instrument. NASA and mission team members encourage the public to process raw JunoCam data into gorgeous imagery as they see fit; to learn more, go to https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu/junocam.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Juno is currently scheduled to continue operating through July 2018, though it could be granted an extended mission beyond that time frame, NASA officials have said. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

Europa Clipper

Unless Juno is exceptionally long-lived, it will be gone before NASA's next mission to the Jupiter system lifts off.

The $2 billion Europa Clipper is slated to launch aboard the agency's huge, in-development Space Launch System (SLS) rocket in 2022. If all goes according to plan, the solar-powered Clipper will settle into orbit around Jupiter in 2025 and then perform about 40 flybys of Europa over the next several years.

During these flybys, Clipper will study Europa with a suite of nine science instruments. (Flying by Europa as opposed to orbiting the moon will greatly reduce Clipper's exposure to powerful radiation, NASA officials have said.) The mission's main goal is to determine if the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 kilometers) moon — which harbors an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust — is capable of supporting life as we know it.

And NASA may get an even closer look at the icy moon. In late 2015, Congress directed the agency to add a lander to the Europa-exploration package. NASA is now studying the best way to do that. Current thinking favors launching a stationary lander separate from the Clipper; once down on Europa, this craft would dig into the ice to search for signs of life. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

JUICE

Like Clipper, JUICE — ESA's first Jupiter effort — is scheduled to lift off in 2022. The 1.5-billion-euro ($1.8 billion) mission will get to the solar system's largest planet in 2029. (JUICE will fly aboard an Arianespace Ariane 5 rocket, not the superpowerful SLS).

JUICE will study Jupiter's atmosphere and magnetic environment, and it will also investigate three of the planet's Galilean moons: Europa, Callisto and Ganymede. (The fourth Galilean moon — which are so named because they were discovered by Galileo Galilei, in 1610 — is the extraordinarily volcanic Io.)

Scientists think oceans of liquid water slosh beneath the icy shells of all three of these Jovian satellites. JUICE's observations should help researchers characterize these potentially habitable environments and better understand how they came to be, ESA officials have said.

Clipper and JUICE "are like close members of the same family. Together, they will explore the entire Jovian system," Curt Niebur, program scientist at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a statement earlier this year.

"Clipper is focused on Europa and determining its habitability," Niebur added. "JUICE is looking for a broader understanding [of] how the entire group of Galilean satellites formed and evolved."

NASA is a key partner on JUICE; the American space agency is providing one of the mission's 10 science instruments, as well as subsystems for two others.

Going back to Saturn — and beyond?

These missions to the Jupiter system do not mean that NASA and planetary scientists have lost interest in Saturn. Indeed, the opposite is true: Multiple Cassini discoveries — of potentially habitable environments on the Saturn satellites Titan and Enceladus, for example — are practically begging for follow-up missions, team members said.

"We left the world informed, but still wondering, and I couldn't ask for more," Cassini project manager Earl Maize, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference Wednesday (Sept. 13). "We've got to go back — we know it."

And NASA is considering going back, as early as 2025. Five of the 12 candidates for the agency's next New Frontiers mission — the same mid-level class as Juno and the New Horizons spacecraft — are Saturn-centric. (One would explore Saturn's atmosphere, two would study Titan and two would investigate Enceladus.)

NASA is expected to whittle this pool down to a few finalists before the end of the year and announce a selected mission sometime in 2019. That mission, whatever it is, is scheduled to launch in 2025.

The space agency may also go beyond Saturn in the next few decades as well. The most recent Planetary Science Decadal Survey — a report produced every 10 years by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences — ranks a Uranus or Neptune orbiter as the third-highest priority for a NASA big-ticket "flagship" mission, behind only a potential Mars sample-return mission and the Europa Clipper.

The earliest feasible Uranus or Neptune launch windows don't open until the 2030s, The Planetary Society's Jason Davis noted in a recent piece.

"Missions to both Uranus and Neptune in the 2040s would actually be ideal, since the planets reach equinox in 2046 and 2050, respectively," Davis wrote. "This would allow the orbiters to observe all latitudes of both planets and their moons, as Cassini did through equinox at Saturn."

A long gap in giant-planet exploration?

NASA has had a significant presence at or around the solar system's four biggest planets — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — for much of the past 45 years.

The agency's Pioneer 10 spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 1973; its cousin Pioneer 11 followed in 1974, and cruised past Saturn in 1979. The twin Voyager probes both flew by Jupiter in 1979, and Voyager 1 had a Saturn encounter in 1980. Voyager 2 zoomed by the ringed planet in 1981, and then flew past Uranus and Neptune in 1986 and 1989, respectively.

The Galileo probe orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003, and the sun-studying Ulysses spacecraft (a joint NASA/ESA effort) made "gravity-assist" flybys of the solar system's largest planet in 1992 and 2004. Cassini orbited Saturn from 2004 until Sept. 15 (and the craft even delivered a lander called Huygens to the surface of Titan in 2005).

The New Horizons spacecraft got a gravity assist from Jupiter in 2007, then famously performed the first-ever flyby of Pluto, in 2015. (New Horizons is current cruising toward its second flyby target, a small object called 2014 MU69, which it will reach on Jan. 1, 2019.)

And you already know about Juno.

So NASA will find itself in relatively new territory after Juno ceases operations, especially if the Europa Clipper doesn't end up launching on time, Davis noted.

"The lights haven't gone out on Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune in more than two decades, and you have to go all the way back to 1972 to find a substantial period when no spacecraft were even in transit," he wrote.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.