The last photos NASA's Cassini spacecraft ever took were of its own grave.

Cassini burned up like a meteor in Saturn's atmosphere early this morning (Sept. 15), ending its historic 13-year study of the ringed-planet system with a dramatic final plunge.

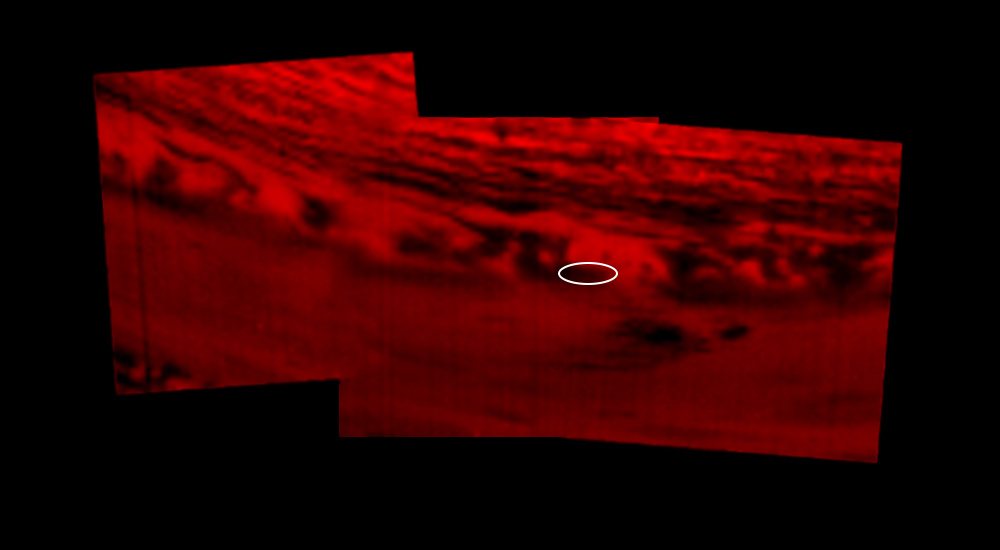

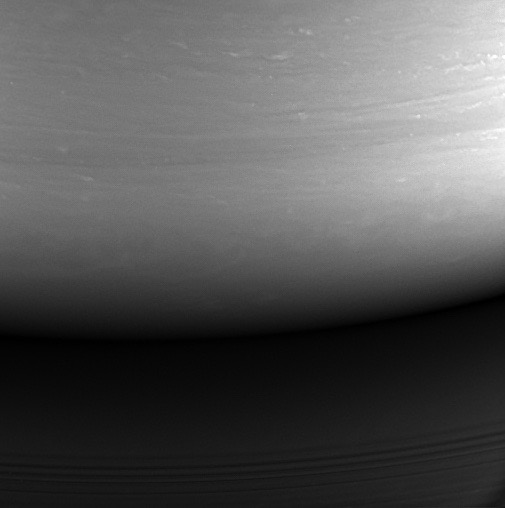

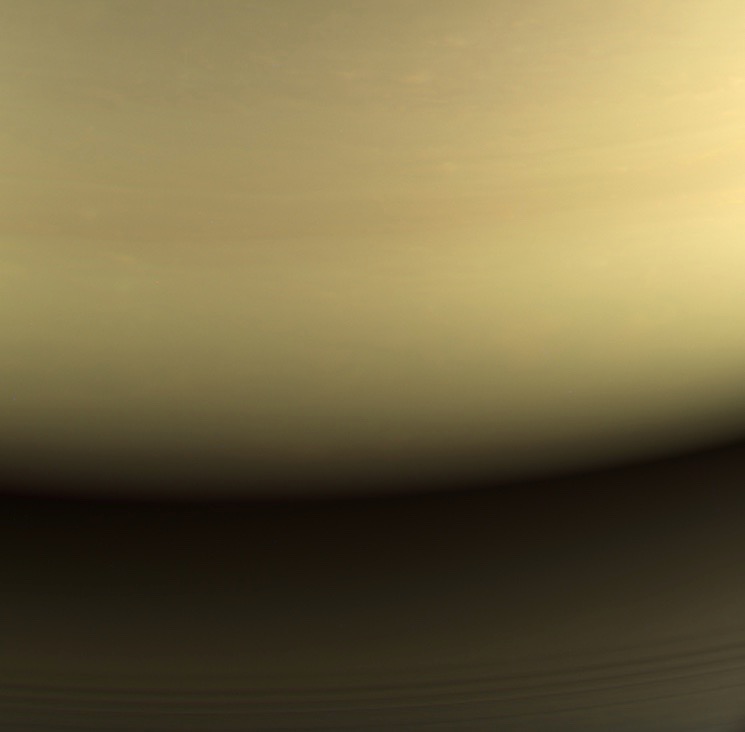

And you can see exactly where Cassini went in, thanks to a series of images the probe took during its approach to the gas giant yesterday afternoon (Sept. 14). [In Photos: Cassini's Last Views of Saturn at Mission's End]

Some of these photos are in visible light, whereas others are in the infrared. All were taken when Cassini was about 394,000 miles (634,000 kilometers) from Saturn, NASA officials said.

The spacecraft burned up in a patch of Saturn sky at 9.4 degrees north latitude and 53 degrees west longitude. The location "was at this time on the night side of the planet but would rotate into daylight by the time Cassini made its final dive into Saturn's upper atmosphere, ending its remarkable 13-year exploration of Saturn," NASA officials wrote in a description of the visible-light images.

Why are there no images from today, during the plunge itself? The mission team prioritized other information, such as measurements of Saturn's atmospheric composition. And the data-transmission rate to Earth was low — so low that images would have hogged too much bandwidth, mission team members said.

Cassini launched in October 1997 and arrived at Saturn on the night of June 30, 2004. The spacecraft made a number of remarkable discoveries over the years. For example, Cassini spotted big hydrocarbon lakes on the hazy Saturn moon Titan and geysers of water vapor blasting from the south pole of the icy satellite Enceladus.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cassini's observations suggest that both of these worlds harbor subsurface oceans of liquid water and may be capable of supporting life. (And Titan may have two different habitable environments; it's possible that "weird life" that depends on liquid hydrocarbons, rather than on water, could exist on the moon's surface, astrobiologists say.)

"I think one of the biggest legacies from Cassini will be the fact that we now know that there are ocean worlds not only around Jupiter, but also around Saturn," Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said during a news conference today.

"You have Enceladus, Titan, perhaps [fellow Saturn moon] Dione, sort of opening up our view of, 'Where could we find life in our solar system?'" Spilker added. "It doesn't have to be in that narrow zone, the 'Goldilocks zone,' where the Earth is."

Indeed, the potential habitability of Titan and Enceladus spurred Cassini's death dive today. The spacecraft's handlers wanted to make sure that Cassini — which was nearly out of fuel — never contaminated either moon with microbes from Earth.

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative effort involving NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. Huygens was a piggyback probe that rode with Cassini and touched down on Titan's surface in January 2005, pulling off the first-ever soft landing on a world in the outer solar system.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.