The Asteroid Belt May Be a 'Treasure Trove' of Planetary Building Blocks

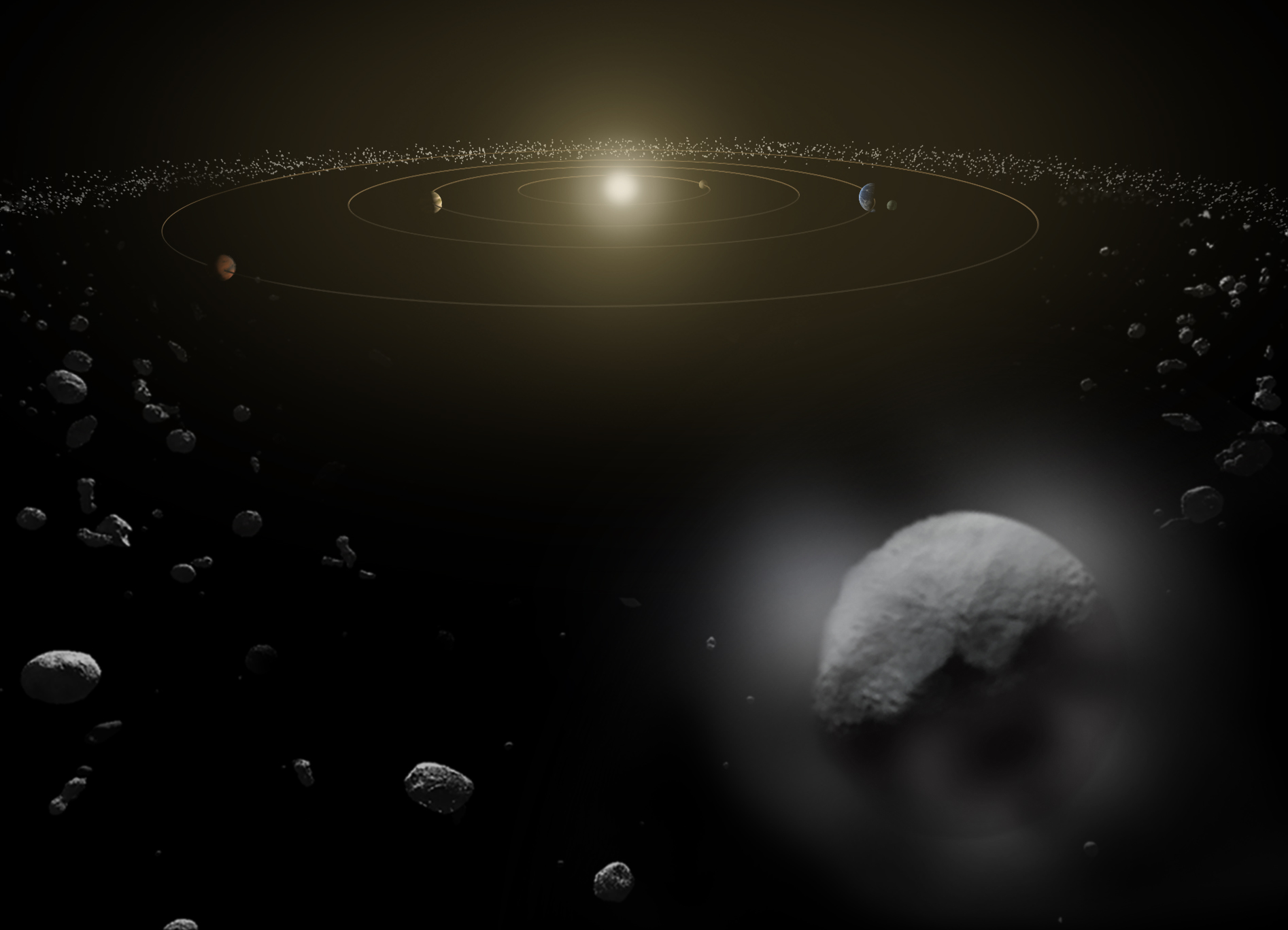

The asteroid belt may have started out empty, later becoming a "cosmic refugee camp" taking on leftovers of planetary formation from across the solar system, a new study finds.

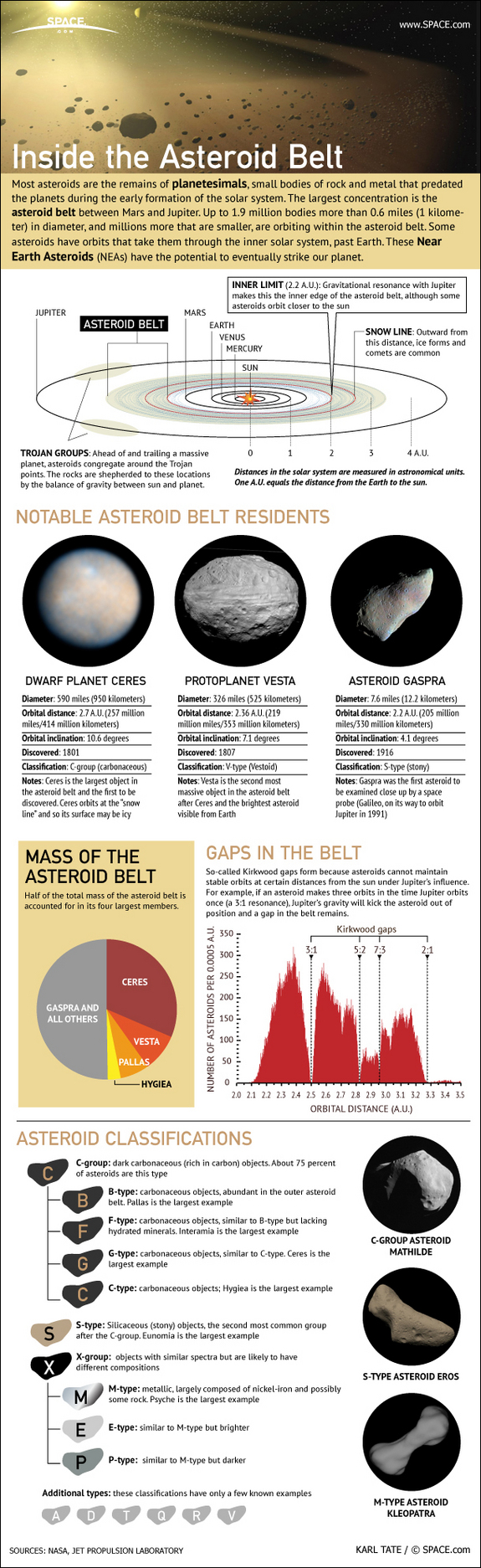

The main asteroid belt, located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, makes up 0.05 percent the mass of Earth. The asteroids there can range greatly in mass, with the four largest ones — Ceres, Vesta, Pallas and Hygiea — holding more than half the belt's mass.

To explain the dramatic range of sizes in the asteroid belt, previous models suggested that the primordial asteroid belt originally possessed a mass equal to at least that of Earth, and that its members had less disparity in mass. The gravitational pulls of the planets later helped whittle down this primordial belt, depleting asteroids of certain sizes more than others. [The Asteroid Belt Explained (Infographic)]

However, these prior models of asteroid formation raised a question: how the belt could have lost more than 99.9 percent of its mass without losing all of it, said study lead author Sean Raymond, an astronomer at the University of Bordeaux in France.

"Our approach is the opposite. We asked the question, 'Could the asteroid belt have been born empty?'," Raymond told Space.com. "The answer is yes, effortlessly."

Birth of the asteroid belt

The scientists developed computer models of an empty primordial asteroid belt to see whether leftovers from planetary formation could explain the belt's current composition. The inner belt is dominated by dry S-type, or silicaceous, asteroids, which appear to be made of silicate materials and nickel iron and account for about 17 percent of known asteroids. The outer belt is dominated by water-rich C-type, or carbonaceous, asteroids, which consist of clay and stony silicate rocks and make up more than 75 percent of known asteroids.

The researchers found that an empty primordial asteroid belt could explain the mass and compositions of the current members of the asteroid belt. This model suggests that this zone between Mars and Jupiter is a repository of planetary leftovers, "a refugee camp housing objects that were kicked out of their homes and left to brave interplanetary space, finally settling onto stable orbits in the asteroid belt," Raymond told Space.com. [The Strangest Asteroids in the Solar System]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In this new model, the inner belt consists largely of rocky leftovers from the formation of the terrestrial planets — Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury. In contrast, the outer belt is made up of remnants of the formation of the gas giant planets, such as Jupiter and Saturn.

"In terms of composition, Jupiter and Saturn grew in a region that was much colder than where the rocky planets grew," Raymond said. "Being colder, their cores could incorporate ice and other volatiles. The C-types are about 10 percent water, whereas the S-types are much drier, having started off in the much hotter terrestrial planet zone."

Relics of the solar system

These findings suggest that the asteroid belt "is a treasure trove — it must contain relics of the building blocks of all the planets," Raymond said. "There must be pieces of terrestrial building blocks out in the asteroid belt, as well as leftovers from building the giant planets' cores."

Future research can further test how well the various models of asteroid-belt formation match reality. Raymond hopes the team's new concept "will help keep people's minds open to potentially drastically different origins stories for the solar system, and for extra-solar planets, too."

Raymond and his colleague Andre Izidoro at the University of Bordeaux detailed their findings online Sept. 13 in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us