Asteroid Odd Couple: Spitting Space-Rock Duo Is Truly Bizarre

In the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, scientists have discovered a pair of space rocks, collectively called 288P, that don't behave like anything previously observed in that region. The rocks' strange characteristics could provide new clues about the formation of planets in the solar system.

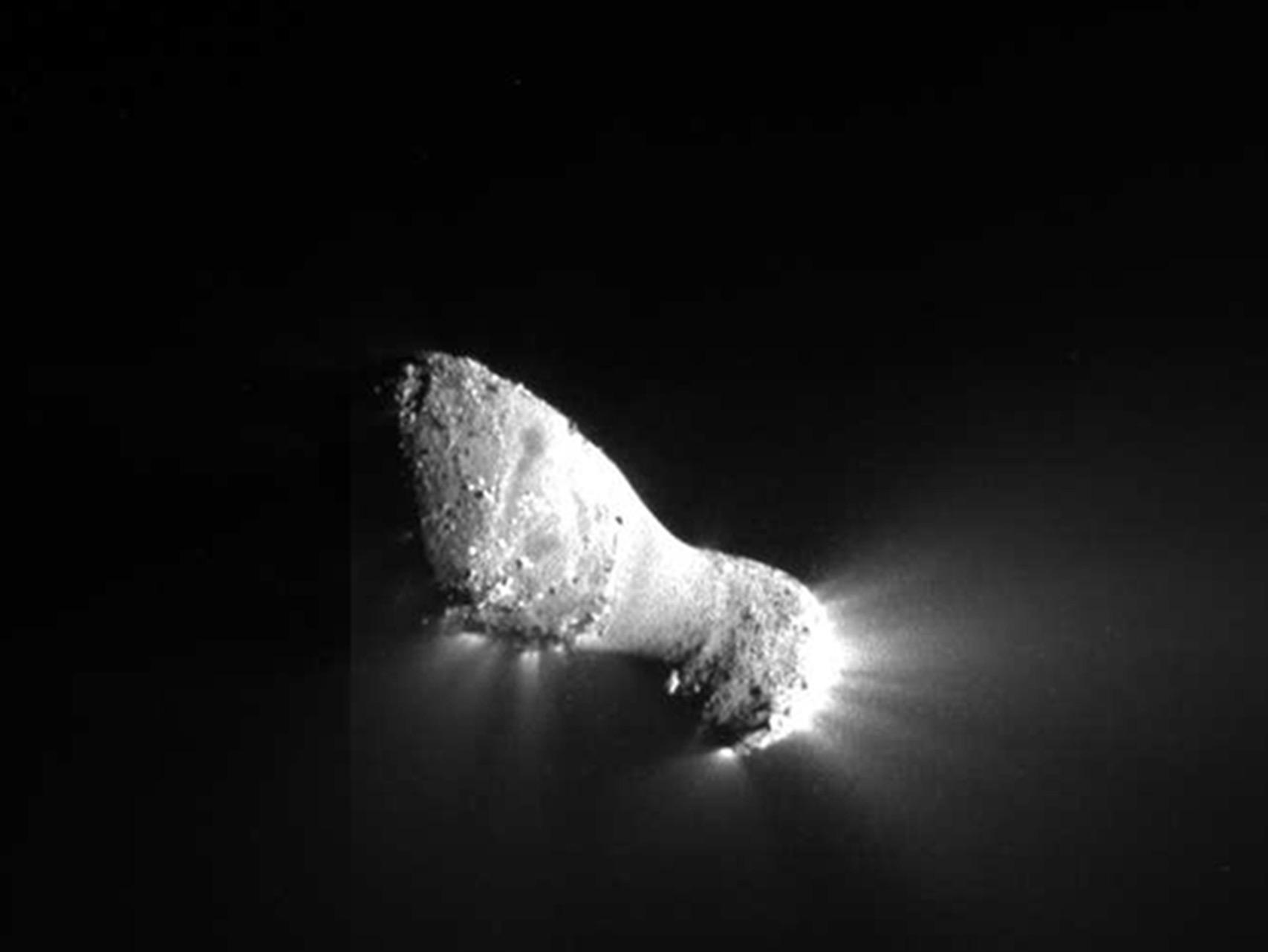

The two asteroids are locked in orbit around each other and are also spewing water vapor into space like comets (which originate in the region beyond Neptune). Many asteroids between Jupiter and Mars can claim one of those characteristics (orbiting one another or releasing vapor), but this is the first time that researchers have identified an object with both features, the researchers said.

"The uniqueness of 288P is the combination [of factors]," Jessica Agarwal, lead author of a paper describing the new research, told Space.com. [The Strangest Asteroids in the Solar System]

And 288P's exclusive mix of traits doesn't end there.

The peculiar rocks were initially identified as a single object, but follow-up observations by Agarwal and her team revealed that 288P consists of two asteroids, each about 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) wide, locked in orbit. Once again, there are many main-belt asteroids in that size group, but the team also discovered that the two rocks are orbiting much, much farther apart than other asteroids of that size typically do.

The asteroids in 288P orbit each other at a distance of about 100 km (about 62 miles), or at least 10 times farther apart than models predict they should be, said Agarwal, who is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany. The rocks' orbits are also highly eccentric (meaning very elongated, rather than closer to a perfect circle), another unique characteristic for two bodies with the size and separation of 288P, Argawal said. The combination of orbital characteristics found with 288P is "different from all other known [asteroid] binaries," she said.

The evolution of asteroids

Why is 288P's unique mix of traits interesting to researchers?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Objects in the asteroid belt have remained almost completely unchanged since the formation of the planets. Therefore, things like asteroid composition provide clues about the material thate formed the planets. Understanding the processes that shape and change those rocks can help scientists piece together the story of how planets formed, and other major questions like why some planets (like Earth) have plentiful amounts of water, while others do not.

The strange orbital characteristics of 288P suggest that multiple factors have influenced the motion of these two objects, Agarwal said. The most surprising finding would be that the comet-like activity on the asteroids is responsible. The ejection of water vapor from the comet into space would push just a little bit on the two pieces, and perhaps, over time, send them reeling into this extreme orbit.

"If that is the case, it basically can change our understanding of how asteroids evolve, so how fast they disintegrate and change their sizes," Agarwal said. "And this in turn can also change our understanding of how they have evolved in the past … [and] our models of the initial distribution of asteroids in the asteroid belt."

In 1996, researchers made the first-ever detection of water vapor spewing off an asteroid in the belt between Mars and Jupiter. Objects in this region have been dubbed "main-belt comets" or "active asteroids" (although some may be spewing dust into space rather than water). Previously, it appeared that the main asteroid belt was a cosmic desert, and water could be found only in ancient space rocks, including comets, orbiting in the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune. Researchers now have strong evidence that Ceres, the largest body in the main asteroid belt, harbors huge amounts of frozen water.

"[NASA's Dawn probe] has certainly shown that there is water ice in the asteroid belt," Agarwal said. "The question is how common it is. We know there has been ice. We know there is ice. But it's hard to say how much." [5 Reasons to Care About Asteroids]

The discovery of main-belt comets provided new possibilities for how planets like Earth got their water, how water was distributed in the early solar system and how it was moved around as the planets took shape, Agarwal said. That information ripples out into studies of alien solar systems and whether it's common for planets to wind up with large amounts of liquid water, a key ingredient for life.

But asteroids are difficult for researchers to study, simply because these space rocks are very small and very dim. The Hubble Space Telescope can see galaxies located many billions of light-years away, but it can barely resolve objects the size of 288P.

Sending spacecraft closer to these bodies to study them in more detail is therefore invaluable to the field. Recent examples of such work include NASA's Dawn mission to the asteroid belt; the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, which landed on a comet in TK; and NASA's Osiris-Rex mission, which is on its way to capture a sample of an asteroid and return it to Earth.

The research paper appears online today (Sept. 20) in Nature.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter