Cosmic Kittens: Saturn Features Get Feline Names

If you know anything about Saturn, you probably know that it's a planet surrounded by rings. But did you know that it's also surrounded by cats?

NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which plunged into Saturn on Sept. 15, has discovered at least 60 "kittens" orbiting in Saturn's F ring. These features aren't actually young cats, but Cassini scientists have been naming them after kittens, mostly just for fun.

Saturn's kittens are a group of small clumps and baby moons, or moonlets, that occupy the planet's F ring. Like the rest of Saturn's rings, this thin outer ring is made up of countless particles that range in size. When enough of those particles bump into one another and stick together, they aggregate into larger clumps — and become eligible for a kitten name.

Photos: Saturn's glorious rings up close

So far, the list of Saturn's kitten names includes several classics, like Fluffy, Garfield, Socks and Whiskers. These are unofficial nicknames for more-complicated (and less adorable) official titles like "Alpha Leonis Rev 9" (aka, Mittens).

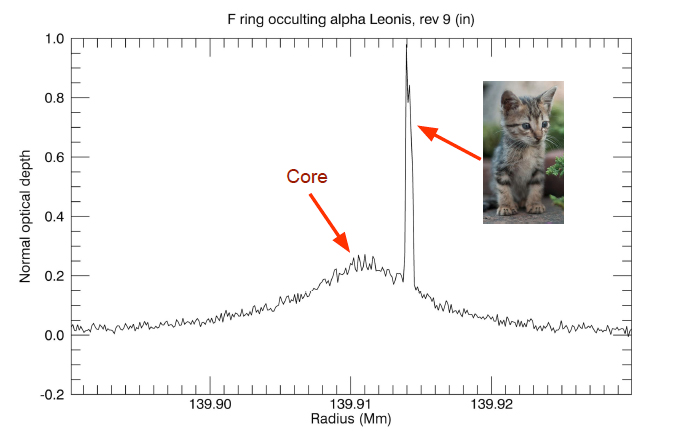

The technical names for these features come from events called stellar occultations, during which Cassini was able to detect the little clumps. In a stellar occultation, a star passes behind Saturn's rings from Cassini's point of view.

"Observing how light behaves as it passes through the particles in Saturn's translucent rings can reveal opaque clumps that Cassini's ordinary cameras couldn't resolve," Larry Esposito, a Cassini scientist responsible for finding and naming the kittens, told Space.com. "The cameras aren't good enough to see the features we're finding, except maybe the very largest ones," he said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Esposito is the principal investigator for Cassini's Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS) experiment, which observed more than 150 different stellar occultations in Saturn's rings during the spacecraft's 13 years at Saturn.

Not only has Esposito's team found about 60 kittens in Saturn's F ring using the UVIS instrument, but Esposito actually discovered the entire ring back in 1979 as a member of the imaging team for NASA's Pioneer 11 spacecraft.

The planetary ring expert now teaches in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, where some of his graduate students have also taken part in the finding and naming of Saturn's kittens while writing research papers about them.

One of those students, Bonnie Meinke — now a deputy project scientist for the James Webb Space Telescope — identified 27 features in Saturn's F ring as Cassini observed 101 stellar occultations between 2004 and 2010. Another student, Morgan Rehnberg, found more kittens with new data collected between 2012 and 2016. Rehnberg brought the kitten tally up to 54, with two moonlets (Mittens and Sylvester) and 52 "kitten-like" features he refers to as "clumps."

Meinke came up with three main categories for the F-ring features. Moonlets "may be solid objects, rather than completely loose aggregations of material that are capable of letting light pass through their porous interiors," Meinke and her co-authors wrote in a paper published in the journal Icarus. "Icicles" are smaller and less dense clumps, while "cores" are variations seen in the ring's structure that aren't associated with solid kitten clumps, the authors wrote. They determined these categories by looking at the shape of each occultation profile, or a graph that shows how starlight behaves as it passes through the ring.

Esposito explained that during a stellar occultation, "We use the flickering of light to measure the structure in the rings just as if you were on your porch watching a car drive by at night where the headlights go past the picket fence. The headlights would blink on and off, and then you could tell how many pickets there were and how wide they were." Similarly, the flickering of light passing through the rings reveals information about what's in the rings.

"Unlike pickets, Saturn's rings are not totally opaque," Esposito said. "You could tell how much light went through at every moment and use that to determine the amount of material at that position in Saturn's rings." These clumps range in size from about 72 feet to 2.3 miles (22 meters to 3.7 kilometers). Esposito and his colleagues have estimated that Saturn's F ring contains about 15,000 Mittens-size clumps, and Mittens measures about 0.4 miles (600 m) across.

Because the particles in the ring are constantly colliding, breaking apart and sticking together, Esposito said that it's possible some of Saturn's named kittens may break apart into smaller kittens or start sticking together like a pile of kittens. "These are like cats, because they have nine lives," Esposito said.

"Most of the clumps are transient. They come and go, and they're small, but some of them get bigger," and they may grow enough to eventually clear a gap through the ring, at which point they could be classified as actual moons, he explained.

However, keeping track of the kittens over time is somewhat of an impossible task, he said. For one, there isn't a spacecraft at Saturn to keep watching the stellar occultations. And even if there were, each kitten sighting is "so rare that we never see them again," he said.

Even if scientists did eventually see one of Esposito's kittens with another spacecraft in the future, researchers may not be able to identify them anymore after all the collisions those kittens would go through in the years between each observation, he explained.

Although it would be nearly impossible to see the same kitten twice, Esposito and his team are still studying and naming Saturn's kittens. "I think this says something about the social nature and humor of the science team," Esposito said. In fact, he said the Cassini team is filled with cat lovers — and a few dog lovers who "resisted" these silly cat names.

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to give more credit to Larry Esposito's graduate students, Bonnie Meinke and Morgan Rehnberg, who helped to conduct this research.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.