How NASA Satellites Are Helping to Halt Malaria Outbreaks

NASA's Earth-observing satellites can track the forces that create malaria outbreaks, and their data will soon help local communities make big strides toward warding off the deadly disease.

The Land Data Assimilation System (LDAS) project allows satellites from far above the Amazon rainforest in South America to track environmental factors (such as rainfall) and human activities (such as logging) that may attract the Anopheles darlingi mosquito, the host of malaria in the region.

NASA's Applied Sciences Program is funding the investigation into using the LDAS to predict malaria outbreaks. William Pan of the Duke Global Health Institute, who is leading the project, said it could be ready to be implemented within a few years, and its analytical models can also be extended to help prevent the spread of Zika, dengue or other diseases. [Why Use Satellites To Measure Rain? (Video)]

By pinpointing areas with warm air temperatures that are likely to have calm ponds or puddles of water, the satellites provide data that Pan and his research team can use, in cooperation with the Peruvian government, to forecast malaria outbreaks down to the household level, NASA officials said in a statement.

Malaria is a deadly global disease that is transmitted by about 40 species of mosquitoes, according to NASA. And in nations like Peru, it is difficult to assess where contaminated female mosquitoes are laying their eggs. The insects look for warm and calm waters, which, according to NASA, can emerge in changing parts of the rainforest, depending on where rainfall accumulates and where logging ditches are dug.

The Amazon basin is witnessing a recent rise in malaria infections, which have particularly severe effects on young children and the elderly. According to the World Health Organization's 2016 Malaria Report, Peru and Venezuela were each experiencing more than 20 percent spikes in estimated malaria cases as well as in estimated mortality rates. People do not always experience their first symptoms of malaria where they contract the disease, so containing an outbreak is challenging. Malaria is passed from female mosquitoes when they feed on blood, and frequently lay eggs as they have short life cycles of just two weeks.

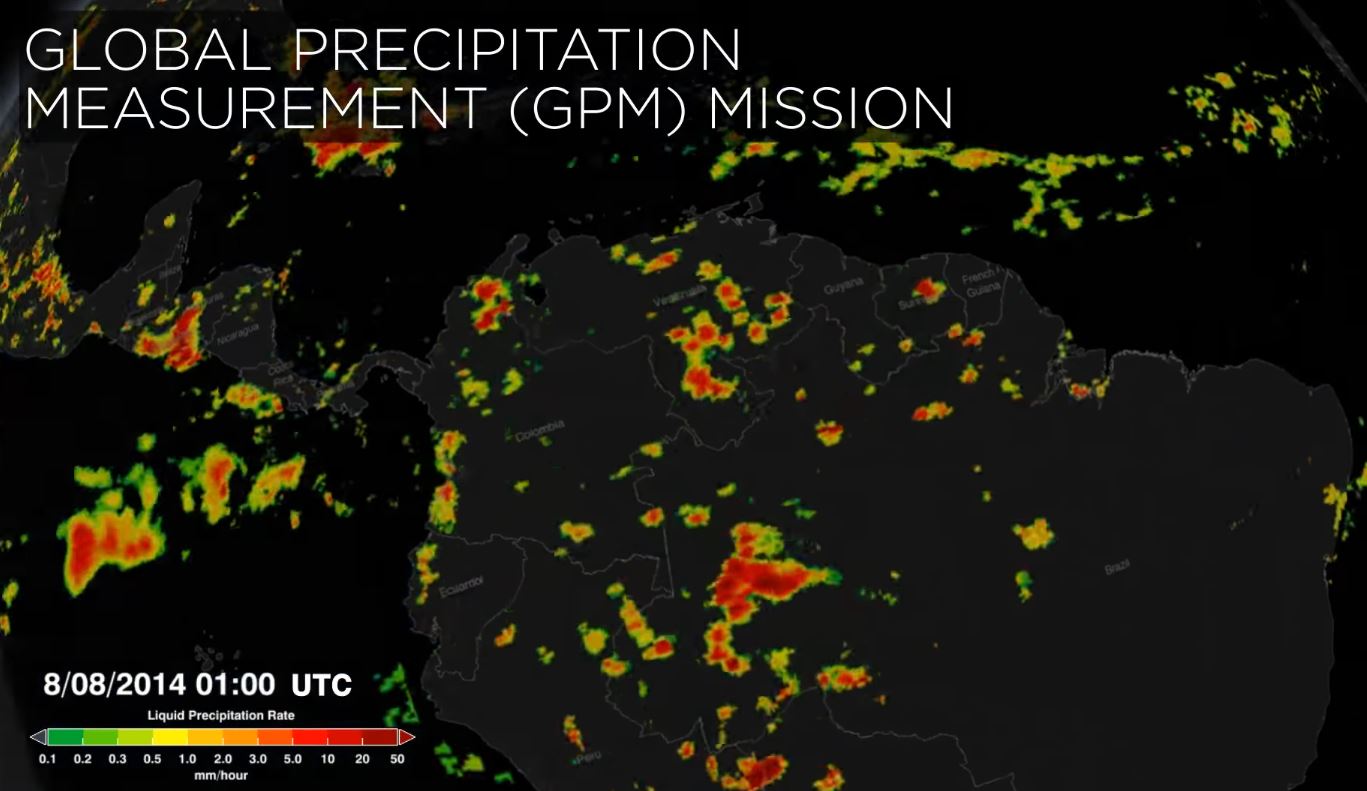

Pan and his team can get data about precipitation, soil moisture, air temperature and vegetation from the LDAS, which folds in data from satellites such as Landsat, Global Precipitation Measurement, Terra and Aqua.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By showing where calm puddles and ponds are likely to form, the team can anticipate where malaria outbreaks are likeliest to occur.

"These models let us predict where the soil moisture is going to be in a condition that will allow for breeding sites to form," Ben Zaitchik, the project's co-investigator, said in the statement.

As NASA satellites detect rainfall, scientists can make predictions about where loggers are likeliest to enter the jungles — and, therefore, where they might catch malaria — since logs are easier to transport via timber floating, where there is a body of water they can travel upon. Malaria is often a byproduct of deforestation, and several nations in the Amazon basin, like Peru, are home to extensive, and sometimes illegal, logging. As the prediction models analyze the data from NASA's satellites, public health officials can make better-informed preparations by sending aid to people living near malaria breeding grounds in the country.

The project is now in the third and final year of its NASA grant, and Pan's team continues to refine the models. The Peruvian government is already familiarizing itself with LDAS, according to NASA, and the malaria prediction tools should be ready for use within the next few years. Colombia and Ecuador, which also have lands inside the Amazon basin, have expressed interest in the initiative.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.