'Alien Megastructure' Ruled Out for Some of Star's Weird Dimming

There's a prosaic explanation for at least some of the weirdness of "Tabby's star," it would appear.

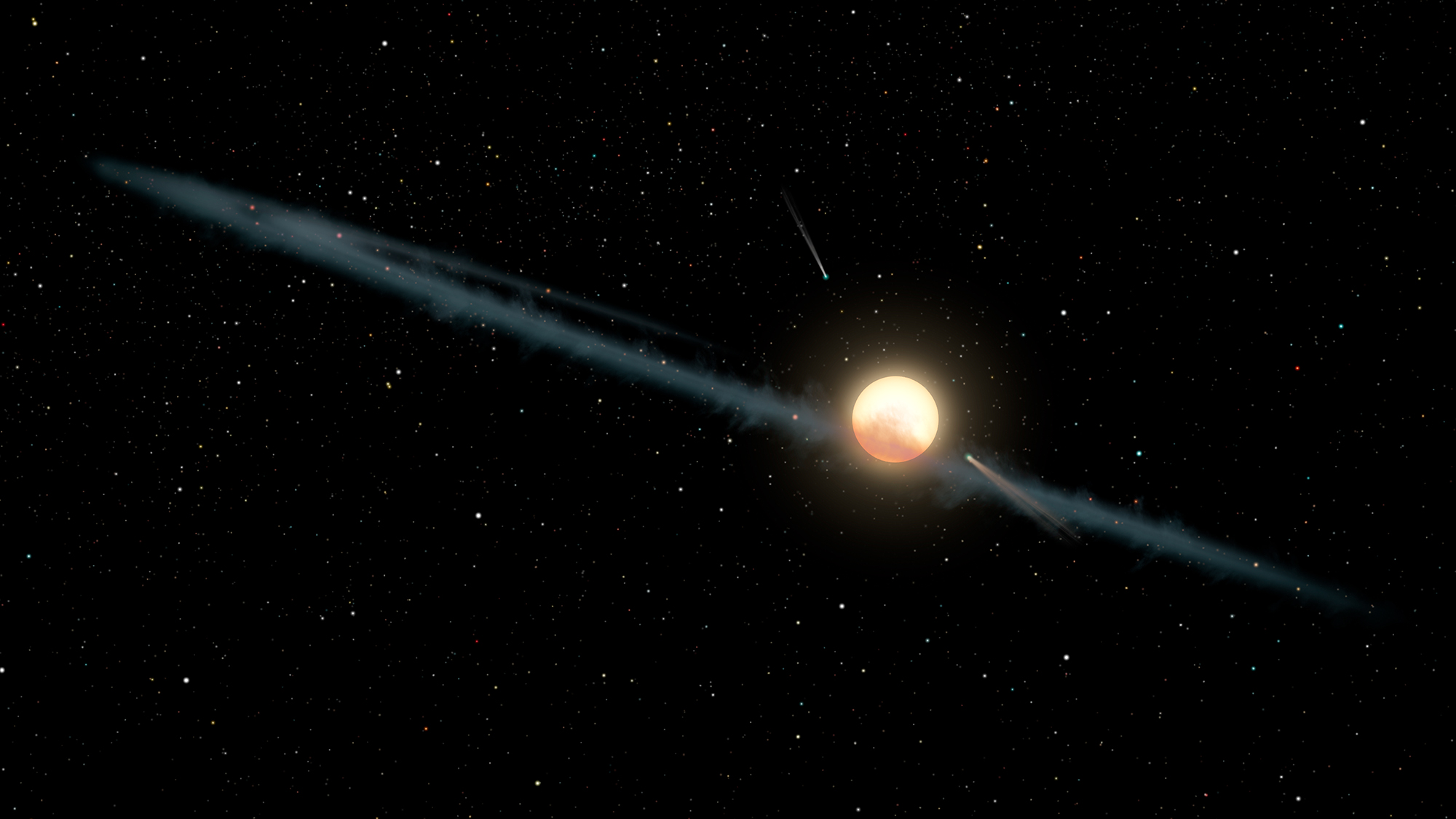

The bizarre long-term dimming of Tabby's star — also known as Boyajian's star, or, more formally, KIC 8462852 — is likely caused by dust, not a giant network of solar panels or any other "megastructure" built by advanced aliens, a new study suggests.

Astronomers came to this conclusion after noticing that this dimming was more pronounced in ultraviolet (UV) than infrared light. Any object bigger than a dust grain would cause uniform dimming across all wavelengths, study team members said. [13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens]

"This pretty much rules out the alien megastructure theory, as that could not explain the wavelength-dependent dimming," lead author Huan Meng of the University of Arizona said in a statement. "We suspect, instead, there is a cloud of dust orbiting the star with a roughly 700-day orbital period."

Strange brightness dips

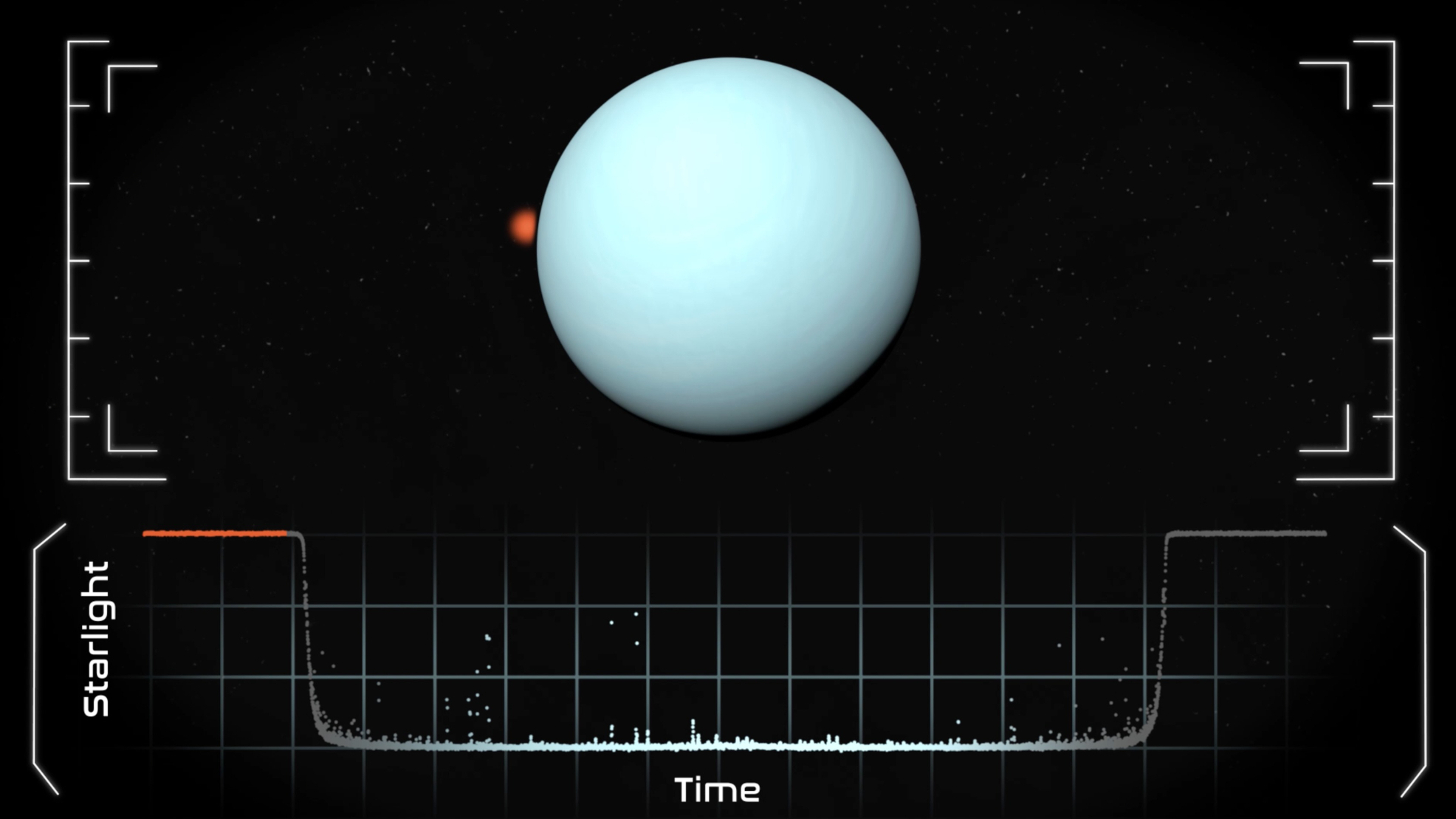

KIC 8462852, which lies about 1,500 light-years from Earth, has generated a great deal of intrigue and speculation since 2015. That year, a team led by astronomer Tabetha Boyajian (hence the star's nicknames) reported that KIC 8462852 had dimmed dramatically several times over the past half-decade or so, once by 22 percent.

No orbiting planet could cause such big dips, so researchers began coming up with possible alternative explanations. These included swarms of comets or comet fragments, interstellar dust and the famous (but unlikely) alien-megastructure hypothesis.

The mystery deepened after the initial Boyajian et al. study. For example, other research groups found that, in addition to the occasional short-term brightness dips, Tabby's star dimmed overall by about 20 percent between 1890 and 1989. In addition, a 2016 paper determined that its brightness decreased by 3 percent from 2009 to 2013.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new study, which was published online Tuesday (Oct. 3) in The Astrophysical Journal, addresses such longer-term events.

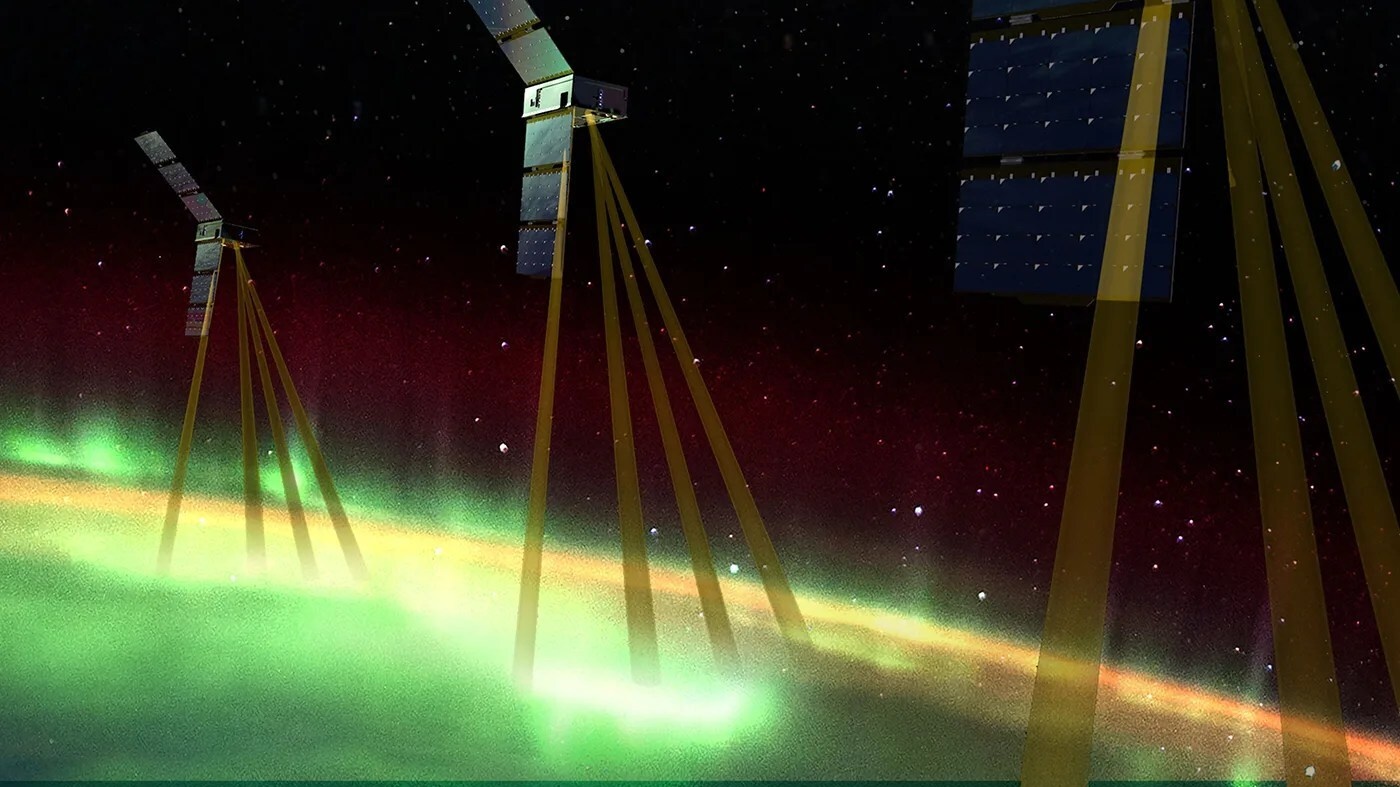

From January 2016 to December 2016, Meng and his colleagues (who include Boyajian) studied Tabby's star in infrared and UV light using NASA's Spitzer and Swift space telescopes, respectively. They also observed it in visible light during this period using the 27-inch-wide (68 centimeters) telescope at AstroLAB IRIS, a public observatory near the Belgian village of Zillebeke.

The observed UV dip implicates circumstellar dust — grains large enough to stay in orbit around Tabby's star despite the radiation pressure but small enough that they don't block light uniformly in all wavelengths, the researchers said.

Mysteries remain

The new study does not solve all of KIC 8462852's mysteries, however. For example, it does not address the short-term 20 percent brightness dips, which were detected by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope. (Kepler is now observing a different part of the sky during its K2 extended mission and will not follow up on Tabby's star for the forseeable future.)

And a different study — led by Joshua Simon of the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Pasadena, California — just found that Tabby's star experienced two brightening spells over the past 11 years. (Simon and his colleagues also determined that the star has dimmed by about 1.5 percent from February 2015 to now.)

"Up until this work, we had thought that the star's changes in brightness were only occurring in one direction — dimming," Simon said in a statement. "The realization that the star sometimes gets brighter in addition to periods of dimming is incompatible with most hypotheses to explain its weird behavior."

You can read the Simon et al. study for free at the online preprint site arXiv.org.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.