NASA Satellite Sees Overheated Tropical Forests Oozing with Carbon Dioxide

NASA's latest carbon dioxide-mapping satellite has detected a dramatic spike in the amount of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, measuring the largest annual increase Earth has seen in at least 2,000 years. The cause? Overheating of three major tropical forest regions across the globe.

NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2), is one of several satellites that collect greenhouse gas emissions data, and researcher Junjie Liu of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, used this probe's data to uncover how much — or in this case, how little — carbon dioxide (CO2) was absorbed out of the atmosphere by Earth's tropical forests.

NASA presented new research findings with a teleconference on Oct 12 that featured Liu alongside Michael Freilich, director of the Earth Science Division at NASA headquarters in Washington, D.C.; Annmarie Eldering, the OCO-2 deputy project scientist at JPL; and Scott Denning, professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University. [CO2 Satellite: NASA's Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 Mission in Photos]

OCO-2 has given scientists a "revolutionary" new way to understand the effects of droughts and heat on tropical rainforests, Freilich said in the briefing. The remoteness of these regions, their lack of field stations and the distorting effect of thunderstorms on land-based measurements of CO2 make the OCO-2 satellite an important and unique tool for monitoring the movement and increase of this greenhouse gas, he added. NASA launched OCO-2 in 2014 just in time for the record spike of global atmospheric CO2 that occurred between 2015 and 2016.

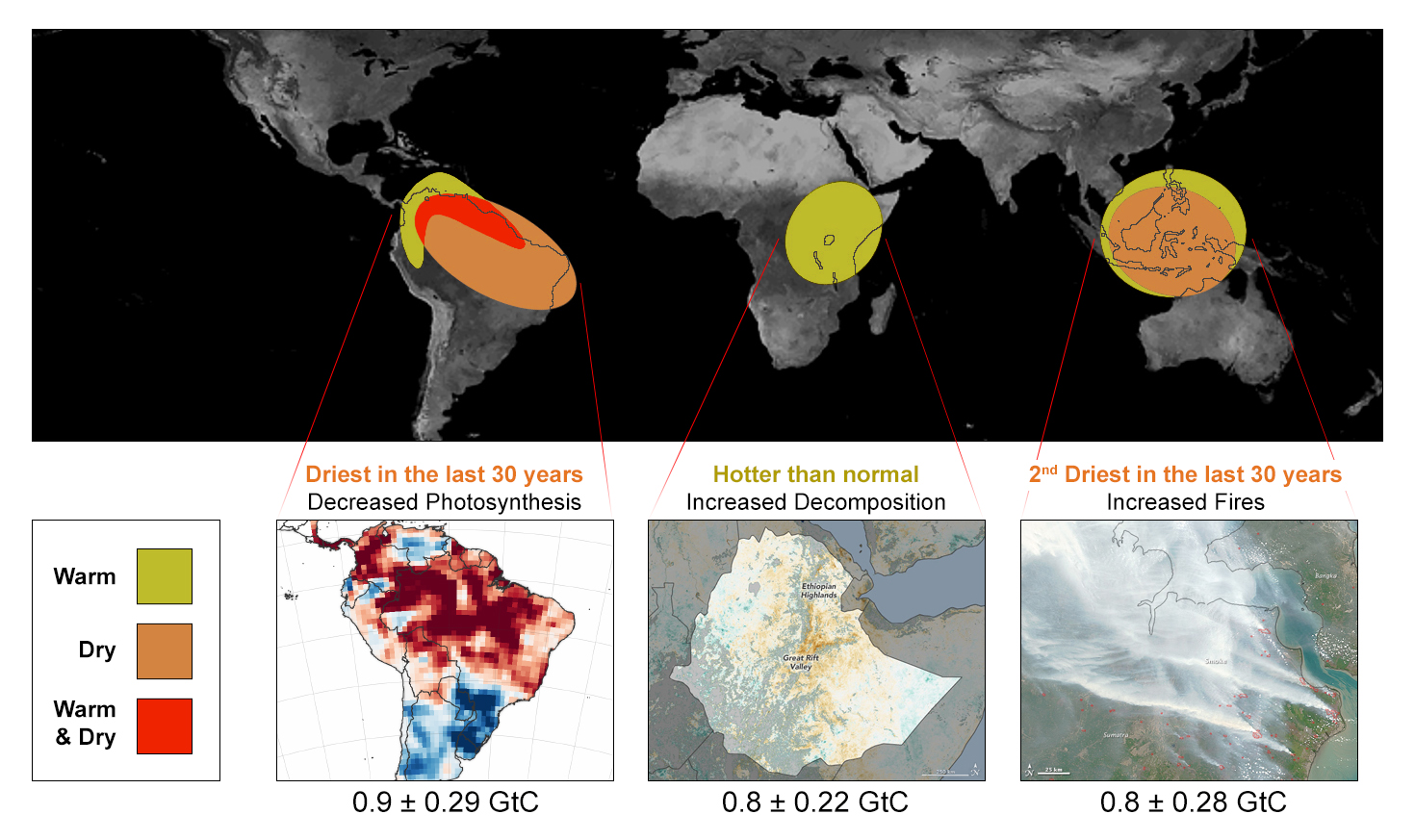

"In both 2015 and 2016, OCO-2 and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) measured the largest annual increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide in at least 2,000 years," Eldering said during the briefing. Using OCO-2 data, Liu quantified that "in total, the three tropical land regions released at least 2.5 gigatons more of carbon into the atmosphere than they did in 2011," or about a 50 percent increase, he said during the briefing.

Droughts in Earth's tropical forests result from the El Niño climate cycle, and El Niño-like weather conditions are expected to become more extreme in the coming years, NASA scientists said in the briefing. This change will make droughts more severe in tropical forests, which could cause even bigger spikes in CO2 levels in the near future.

As plants experience warmer and drier conditions, they're more likely to dry out and rot, producing more CO2 instead of removing it from the atmosphere like healthy plants do. Without enough plants to perform photosynthesis and filter CO2 out of the air, the tropical forests will not be able to soak up as much of the greenhouse gas emissions that are increasing global temperatures across the planet, NASA scientists said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Eldering explained that OCO-2 takes about 100,000 direct and daily measurements of CO2 over the tropical forest regions of South America (like the Amazon rainforest), the tropical forests of Africa and the tropical region of Asia surrounding Indonesia.

As the OCO-2 satellite orbits Earth from one pole to the other, measuring CO2 levels around the world, it also senses the rate of photosynthesis by detecting fluorescent chlorophyll in vegetation on the ground. These measurements help scientists produce models of plant decomposition rates across the globe.

"The OCO-2 satellite allowed our team to quantify how the net exchange of carbon between land and atmosphere in each tropical region was affected by the 2015-2016 El Niño," Liu said. "To put that in perspective," Eldering added, "that is equal to almost a third of all carbon dioxide emitted from human activities during that same time period."

The Amazon basin, according to Liu's findings, experienced the most severe drought in 30 years. Precipitation data from satellite measurements and terrestrial rain data revealed that plants were decomposing faster in the tropical forests in Africa, thereby releasing more CO2 and absorbing less of it. The heat from forest fires in Indonesia — some of which were human-made — also increased tropical Asia's carbon dioxide release.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.