2017 Orionid Meteor Shower Peaks This Weekend: What to Expect

Over the next several days, you may get a chance to glimpse a "shooting star" in the predawn hours, as the Orionid meteor shower will be at its peak.

This meteor display is spawned by the debris shed by Halley's Comet, and if you spot one of these meteors,there's a good chance that what you saw was a fragment left behind in space by this famous comet.

This year will present an excellent opportunity tosee the Orionids,as the moon will be a mere sliver and will set soon after sunset, ensuring that its light will not hinder views for skywatchers looking for meteors during the prime viewing hours before dawn. [Orionid Meteor Shower 2017: How and When to See It]

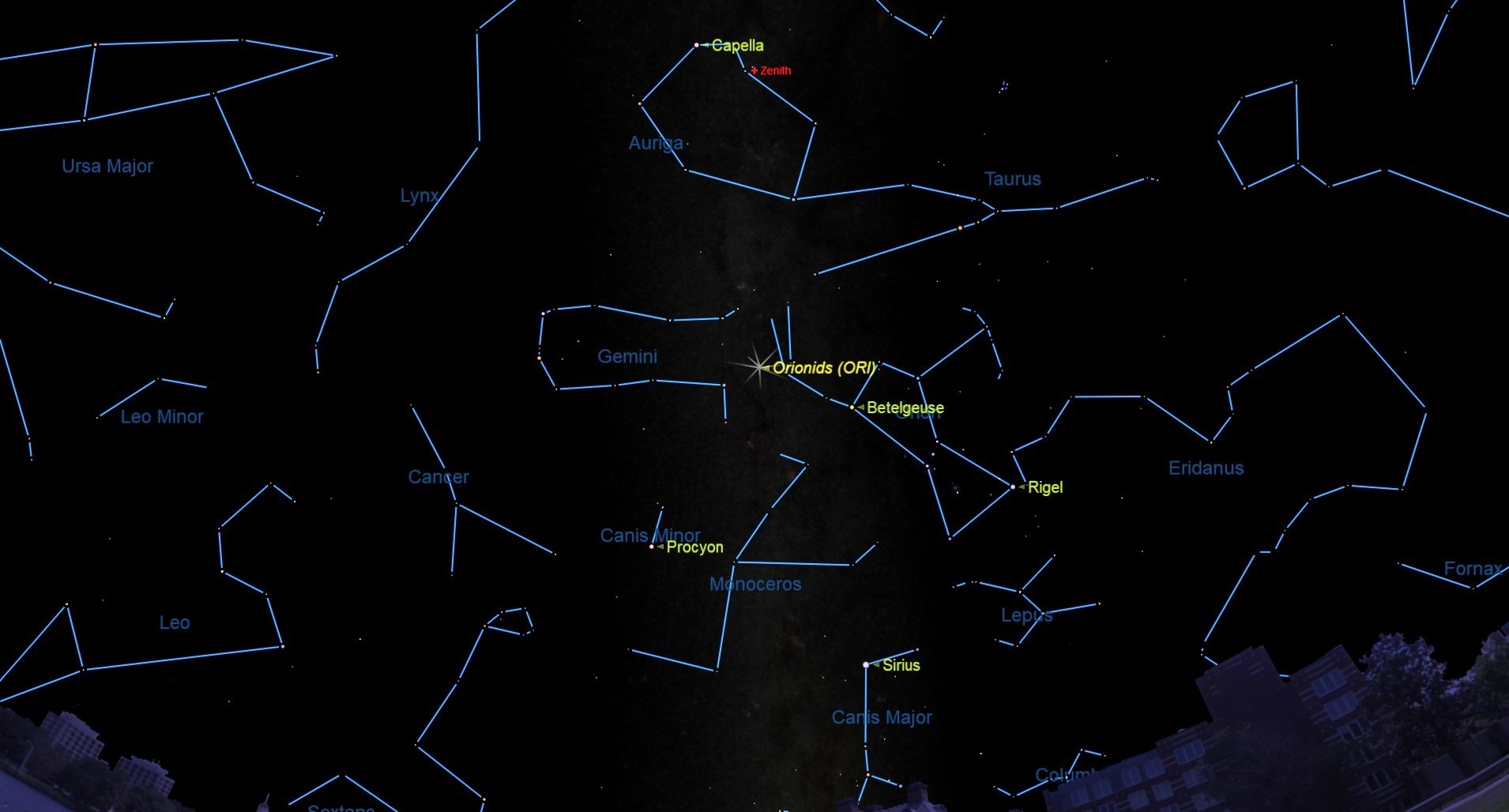

If August's Perseid meteor shower and December's Geminid meteor shower rank as the "first string" among the annual meteor showers in terms of brightness and reliability, then the Orionids are on the junior varsity team. In 2017, they reach their maximum before sunrise this Saturday (Oct. 21). The event gets the "Orionid" moniker because the radiant — the spot on the sky from which the meteors appear to fan out — is just above the ruddy Betelgeuse, the second-brightest star in the constellation Orion.

Know where to look

Orion is a winter constellation; in early autumn, it appears ahead of us in our path around the sun and, as such, does not completely rise above the eastern horizon until after 11 p.m. local time. Several hours later, between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m., Orion will be high in the sky toward the south-southeast.

But to see the greatest number of meteors, don't look in the direction of the radiant, but rather about 30 degrees from it, toward the point directly overhead (the zenith). Your clenched fist held at arm's length is roughly equivalent to 10 degrees, so concentrate your view three fists up from Betelgeuse.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Typically, Orionid meteors are dim and hard to see from urban locations, so you should find a dark (and safe) rural location to get the best views of Orionid activity.

Best times to watch

The Orionids are visible from Oct. 16 to Oct. 26, with peak activity of perhaps 15 to 30 meteors per hour coming on the morning of Oct. 21. Step outside before sunrise on any of these mornings, and if you spot a meteor, there's about a 75 percent chance that it's a byproduct of Halley's Comet. The last Orionid stragglers usually appear sometime in early to mid November.

The best time to watch is from about 2 a.m. local time to the first light of dawn, when the Orion, the Mighty Hunter, appears highest above the horizon. The higher in the sky Orion is, the more meteors will appear all over the sky. The Orionids are one of just a handful of known meteor showers that can be observed equally well from the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

Orionid meteors are the very fastest of the principal meteor displays that occur during the year, piercing Earth's upper atmosphere at speeds averaging 41 miles per second (66 kilometers per second). As such, they appear as swift, incandescent streaks, darting across your line of sight in a second or less. These meteors sometimes leave fine glowing trains in their wake, enhancing the spectacle for meteor watchers.

Halley's legacy

Right now, Halley's Comet is nearing the far end of its long elliptical path around the sun, out beyond the orbit of Neptune. It will arrive at aphelion — its farthest point from the sun — in December 2023.

The comet's last visit through the inner solar system was in late winter 1986, and it is due back in summer 2061. But each time it has swept past the sun — and it has done so hundreds, if not thousands, of times — it has released tiny particles, mostly ranging in size from dust to sand grains, which travel near and along the comet's orbit, creating a dirty trail of debris that has been distributed more or less uniformly all along its orbit.

And it turns out that, in its annual trek around the sun, Earth passes quite close to the orbit of Halley in two places. One point is in early May, when it produces a meteor display known as the Eta Aquaridmeteor shower. The other point comes in mid to late October, when it produces the Orionids.

Comets are composed of frozen gases—such as methane, ammonia, carbon dioxide and water vapor — that went unused when the sun and planets came into their present form. These gases become heated as they approach the sun and are made to glow by the sun's light. As the gases warm and expand, the solar wind — the stream of charged particles that flows outward from the sun — blows this expanding material out into the comet's beautiful tail.Dusty material that is released into space was once part of the comet's nucleus.

The fiery streaks that will be visible over the next several nights will likely be the material shed from the nucleus of Halley's Comet.

So the shooting stars that we have come to call Orionids are really an encounter with the traces of a famous visitor from the depths of space and from the dawn of creation.

Editor's note: If you snap a great photo of an Orionid meteor or any other night sky sight you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments in to: spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, New York.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.