Dawn Spacecraft Will Remain at Dwarf Planet Ceres Until It Runs Out of Fuel

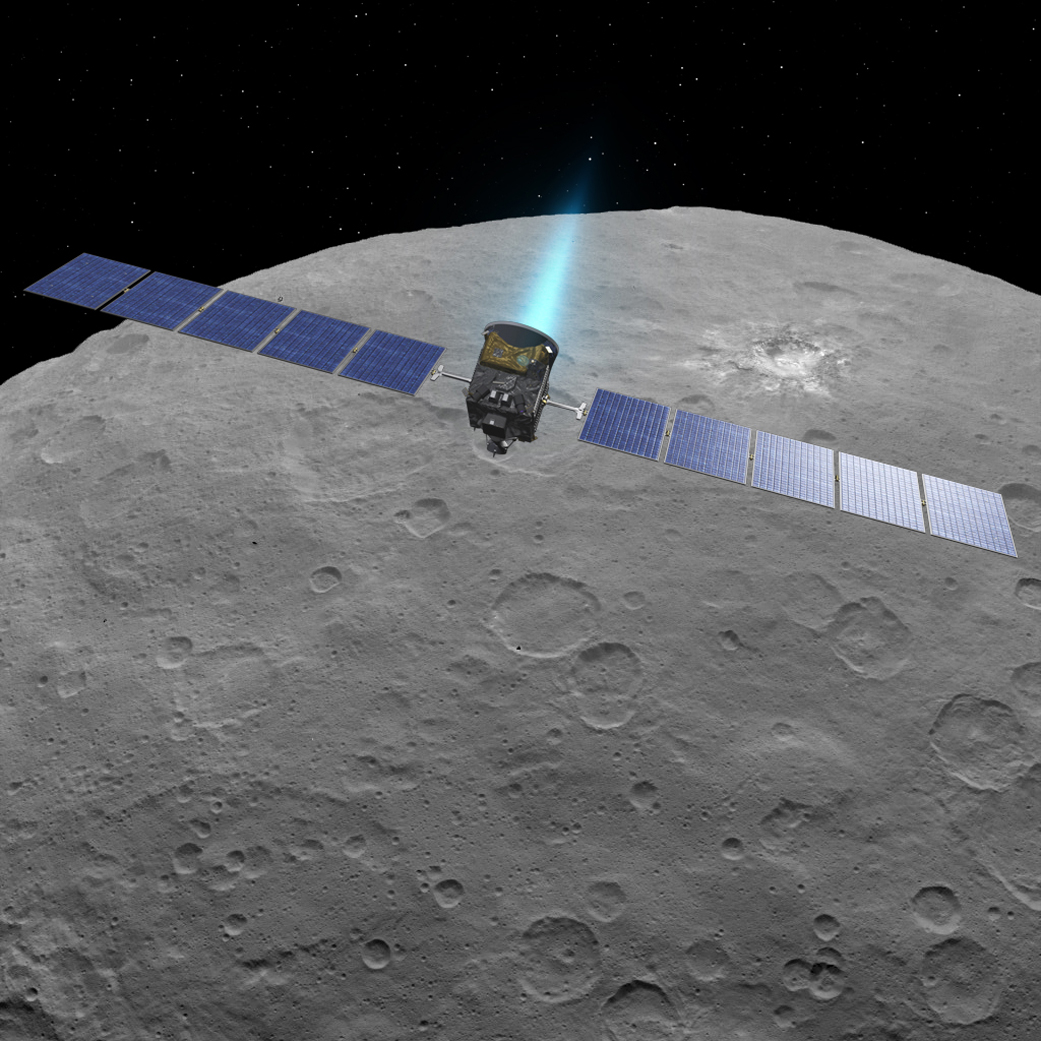

NASA officials have decided that the Dawn spacecraft will spend its last days studying the dwarf planet Ceres. Rather than move on to another target for its final hurrah, Dawn will remain at Ceres until it runs out of fuel, which should happen around the middle of 2018.

The decision grants Dawn a second extended mission, during which the spacecraft will dip down to an altitude of just 120 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface of Ceres, according to a statement from NASA. This will be the closest that the probe has ever come to Ceres, having previously reached a low altitude of 240 miles (385 km).

The mission will continue until Dawn uses up the last of its hydrazine fuel, which is used to change the spacecraft's orientation. Dawn is expected to continue operating "until the second half of 2018," according to the statement, but the exact date will depend on what activities the mission team decides to execute. [Dwarf Planet Ceres, the Solar System's Largest Asteroid]

"How quickly we will use the hydrazine will depend on details of the observations that we have not yet designed, so we do not have a precise time frame," Marc Rayman, the Dawn chief engineer and mission director, told Space.com in an email. "When the last of the hydrazine is exhausted, the spacecraft will no longer be able to control its orientation, so it won't be able to point its solar arrays at the sun, its sensors at Ceres, nor its antenna at Earth. That will be the end of Dawn's operational life."

Dawn began orbiting Ceres in March 2015. It is the only spacecraft to have orbited two celestial bodies, having looped around the large asteroid Vesta from 2011 to 2012. In 2016, NASA was considering a proposal to send Dawn to a third target in the asteroid belt.

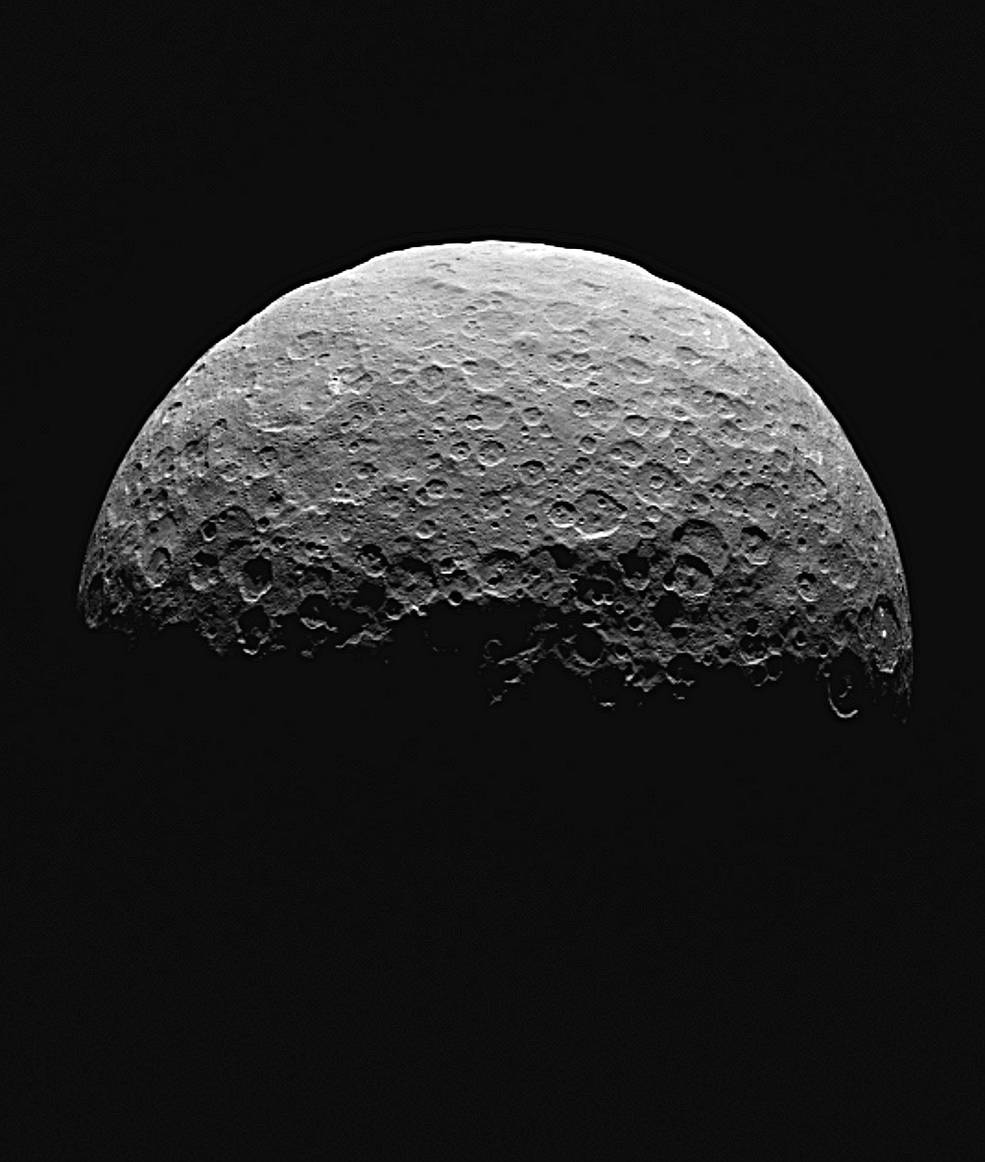

These giant asteroids have remained largely unchanged since the birth of the early solar system (though they are not entirely inactive), and studying them can help scientists better understand the evolution of the solar system and the conditions in which the planets formed, according to NASA.

One of Dawn's primary avenues of investigation is to understand how much water is present on Ceres. The close flyby will allow one of the probe's instruments, called the Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRaND), to produce a more detailed map of chemical elements on the surface of Ceres, including water, according to the statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ceres is approaching its closest position to the sun (called perihelion), and its close proximity to the star could help scientists test two hypotheses, according to the statement. The first is that water ice in Ceres' surface is warmed up and turned into vapor, which helps to create the thin atmosphere that was detected around the dwarf planet prior to Dawn's arrival, but which occasionally disappears.

The second hypothesis is that water vapor contributing to the atmosphere could also be created by energetic particles (other than photons) "interacting with ice in Ceres' shallow surface," officials said in the statement. Ground-based telescopes will also keep an eye on Ceres as it approaches its April 2018 perihelion, to assist in these investigations.

"I am really excited about the extension, and so is the entire team," Rayman said. "Dawn has already revealed Ceres to be an exotic world of ice, rock and salt, with organic materials and other chemical constituents, and I am looking forward to more discoveries about its composition and its geology. After all, the benefit of having the capability to orbit a distant destination, rather than being limited to a brief glimpse during a flyby, is that we can linger to scrutinize it and uncover even more of the secrets it holds. I don't know what we'll find, and that is part of the process of science and the thrill of exploration."

When Dawn finally runs out of fuel, it will remain in orbit around Ceres for at least 50 years. NASA's Planetary Protection Office required the mission planners to guarantee that the probe would not crash into Ceres' surface less than 20 years after arriving at the dwarf planet, according to the agency. This decision helps to ensure that any microscopic life-forms that piggybacked on Dawn from Earth will be killed by the space environment, and will not invade any potentially habitable environments on Ceres.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter