How Complex Chemistry Created a Toxic Cloud on Saturn's Moon Titan

There's a toxic ice cloud lurking over Saturn's moon Titan.

The cloud, discovered by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, consists of hydrogen cyanide and benzene, according to a statement from the agency. The presence of those chemicals in Titan's atmosphere isn't a surprise, but this is the first time scientists have seen them condense together at the same time, to form one cloud rather than separate layers.

"This cloud represents a new chemical formula of ice in Titan's atmosphere," Carrie Anderson, a Cassini scientist, said in the statement. [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

Titan is the only body in the solar system besides Earth with liquid on its surface; however, its lake, oceans and rivers are full of liquid methane instead of water. Researchers have found organic molecules on Titan (meaning those that are necessary to create life as we know it, but not necessarily a sign of life on their own), and a wealth of other complex chemicals. Researchers continue to probe Titan for clues about how life might emerge in alien environments.

Chemical clouds

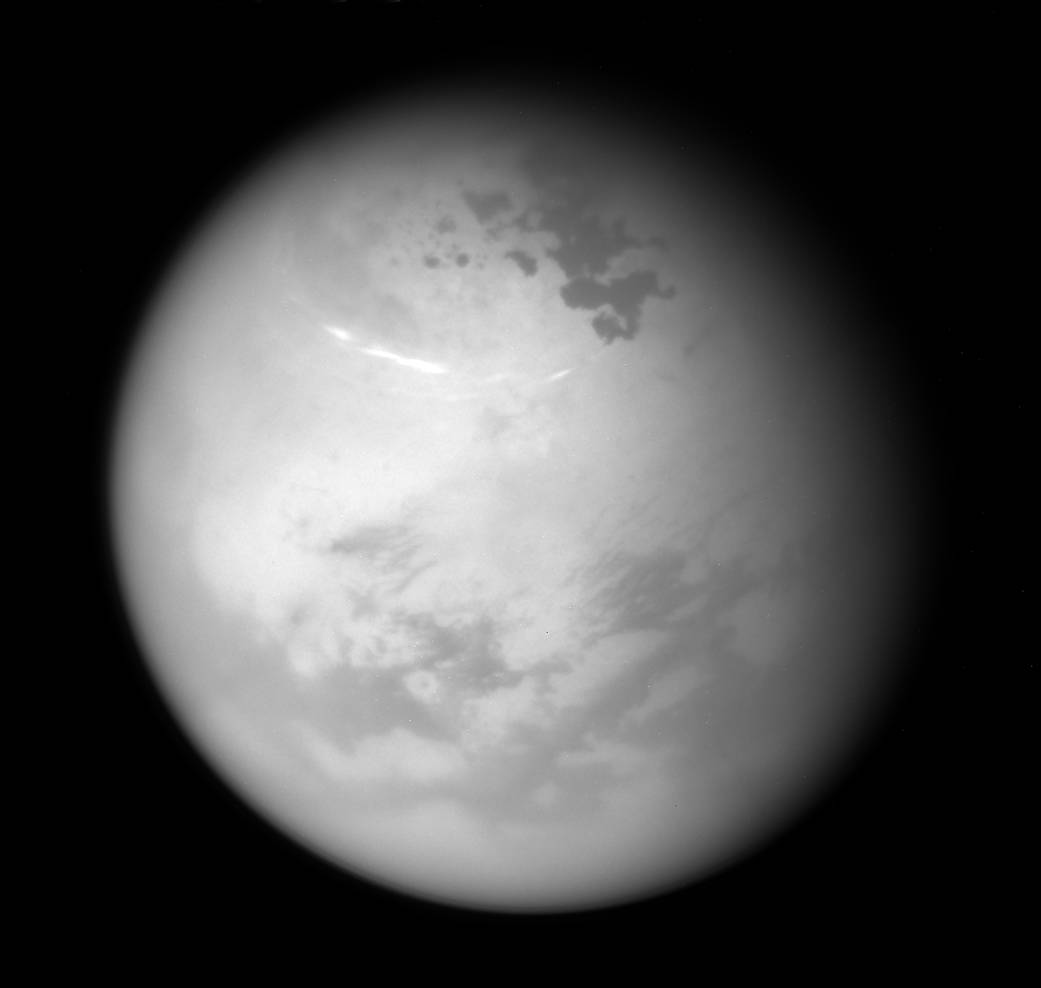

The toxic cloud was spotted in three separate observations by Cassini between July and November 2015. It was located near Titan's south pole, in the moon's stratosphere, high above the thick methane clouds that make Titan look like an opaque yellow marble to the naked eye. (Cassini can see through these clouds to the moon's surface using different wavelengths of light.)

The cloud was identified by the Composite Infrared Spectrometer, or CIRS instrument, on Cassini, which uses a technique called spectroscopy to find out what chemicals are present in things like clouds on Titan. Spectroscopy takes the light from an object and spreads it so that the individual wavelengths of light are revealed. Every chemical has a unique spectral "fingerprint" that reveals its identity, but sometimes combinations of chemicals can produce new spectra. When the researchers looked at the cloud's spectra, they saw that it must be a combination of chemicals.

So, the researchers went to the lab and used a sealed chamber to make ice clouds from various gases known to be present on Titan. The best fit to the cloud's spectrum was a combination of hydrogen cyanide plus benzene, in which the gases had condensed into ice at the same time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Titan's atmosphere is rich with different chemicals that can condense into icy clouds. In a simple atmospheric model, each type of chemical vapor could form a distinct layer of clouds, according to NASA. But because of complicating factors like the amount of vapor present, its temperature, and because an individual cloud will actually form across a range of altitudes, vapors of various chemicals can freeze together into clouds at the same height, creating a variety of chemical combinations, officials said in the statement.

Although the Cassini mission ended in September, when mission planners intentionally sent it hurtling through Saturn's atmosphere, researchers are still learning about the Saturn system using data from the probe.

The mixing is also encouraged by the seasonal cycles on Titan. During one hemisphere's summer season, a cycle of warm winds is pushed away from that hemisphere toward the opposite pole, where it is winter, according to the statement. As a result, there's a buildup of clouds in the winter hemisphere. The toxic cloud was spotted two years before the southern hemisphere's winter solstice. (Seasons on Titan last about seven Earth years).

"One of the advantages of Cassini was that we were able to flyby Titan again and again over the course of the 13-year mission to see changes over time," Anderson said. "This is a big part of the value of a long-term mission."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter