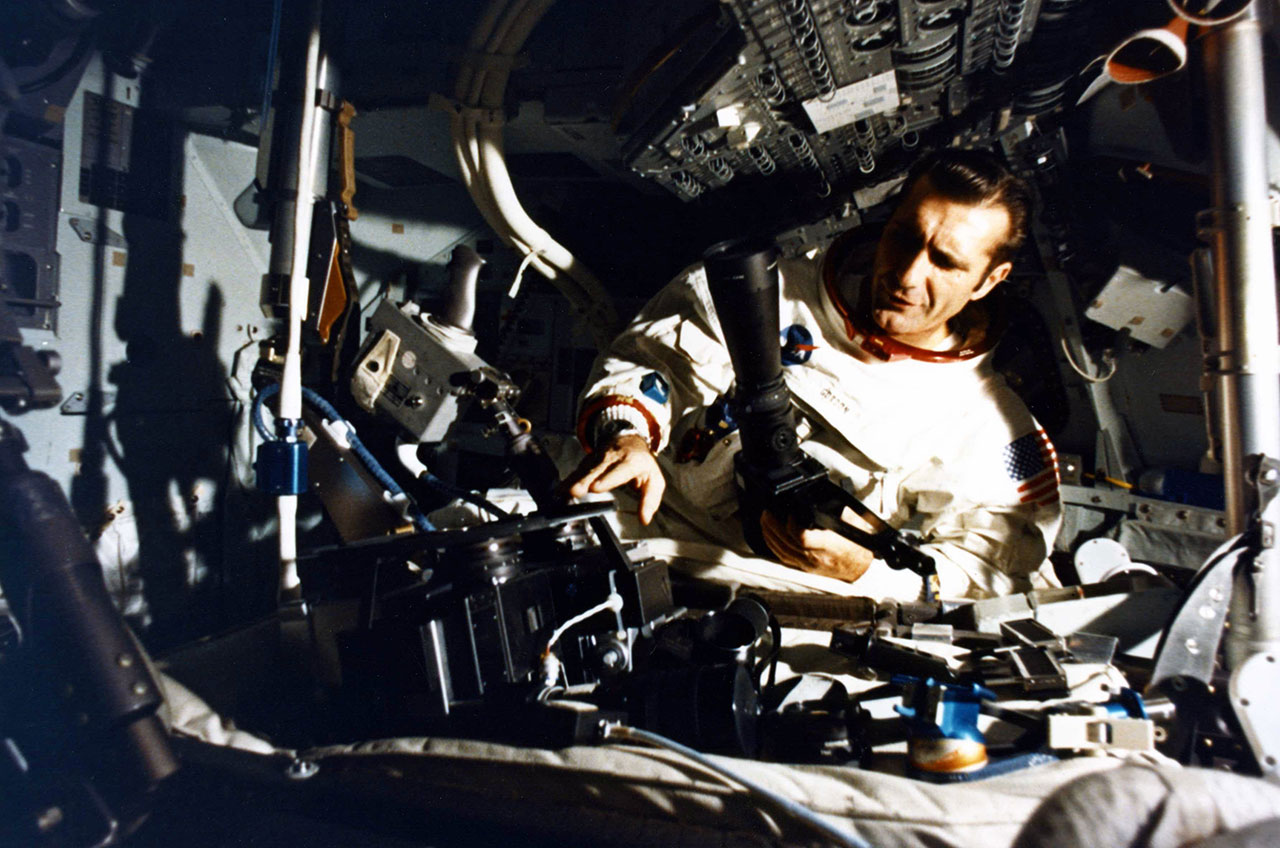

Dick Gordon, Astronaut Who Walked in Space and Flew to Moon, Dies at 88

Richard "Dick" Gordon, an Apollo-era NASA astronaut who became the fourth American to walk in space and one of 24 humans to fly to the moon, died on Monday (Nov. 6) at the age of 88.

Gordon's death was confirmed by NASA and the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. A cause of death was not stated.

"We lost a good friend and former director," Tammy Sudler, president and CEO of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation, wrote in an email to supporters on Tuesday afternoon. "Dick always did everything in style and his way. He was loved by many and will be missed by all." [Project Gemini: NASA's 2-Person Space Missions in Pictures]

Gordon was chosen with NASA's third group of astronauts in 1963. He flew two times to space: first as pilot of Gemini 11 in 1966 and then as Apollo 12 command module pilot in 1969.

In total, Gordon logged 13 days, 3 hours and 53 minutes in space, including 2 hours, 41 minutes on two extravehicular activities (EVAs, or spacewalks) and 88 hours, 58 minutes in orbit around the moon.

"NASA and the nation have lost one of our early space pioneers," said acting NASA Administrator Robert Lightfoot in a statement. "Dick will be fondly remembered as one of our nation's boldest flyers, a man who added to our own nation's capabilities by challenging his own."

Gordon's first launch into space came on Sept. 12, 1966, on board NASA's ninth and second to last Gemini crewed mission. Lifting off on a Titan II rocket from Complex 19 at Cape Canaveral, Gordon flew with Gemini 11 commander Charles "Pete" Conrad, his former roommate from his days as a naval aviator on the aircraft carrier USS Ranger.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Pete and I could communicate without talking. We trusted each other. We thought alike," said Gordon in a NASA oral history. "We reacted to the same stimuli the same."

Gordon and Conrad lifted off at 9:42 a.m. EST (1442 GMT) and attached to an Agena docking target just one hour and 34 minutes later, demonstrating the capability to do a first-orbit, direct ascent rendezvous.

"It was pretty dynamic and pretty exciting," Gordon told the NASA interviewer, "when you're launched after the Agena and your rendezvous was by the time to get to Hawaii and dock was by the time you get to the United States."

Conrad and Gordon used the engine on the Agena to raise their orbit to 850 miles (1,370 kilometers), which is still the highest Earth orbit achieved by a crewed spacecraft to this day.

During the three-day-long mission, Gordon performed two EVAs. On his first spacewalk, he fastened a 100-foot-long (30-meter) tether from the Agena to a bar on the outside of the Gemini capsule, but not without significant trouble.

"In training, I had been able to wedge my legs between the Agena and Gemini ... and then be able to use both hands to attach the tether," Gordon stated. "Well, I couldn't keep myself in that position. I kept floating away, so I ended up having to hold the docking bar with one hand and put the tether and the locking mechanism on there with the other."

"I have always equated that to the task of trying to tie your shoelace with one hand," he said.

Perspiring to the point that salt from his sweat was stinging his eyes, Gordon returned inside the spacecraft a half hour earlier than was planned. But with the tether successfully connected between the two vehicles, Conrad and Gordon were able to use the thrusters on the Gemini to begin the two craft rotating and produced a small amount of artificial gravity as an experiment.

"We knew we could feel the gravity. It was very, very low. But you could feel it," Gordon described, adding that after releasing a pencil, he and Conrad were able to watch as it was pulled away. "So, you knew right then and there that you were creating artificial gravity."

Gordon's second spacewalk went more smoothly, standing up in his seat to photograph Earth and the stars.

"The second EVA was easy," he recalled. "Standing up in the hatch, outside the spacecraft, but pointing this camera or the spacecraft at a particular area in the solar system."

"I fell asleep during EVA. That's how difficult EVA is when you can fall asleep. It was a totally different experience."

Conrad and Gordon splashed down aboard Gemini 11 on Sept. 15, 1966, and were recovered in just 24 minutes by the USS Guam aircraft carrier.

It was not the last time the two would fly together.

Three years later, on Nov. 14, 1969, Gordon, Conrad and Alan Bean launched on Apollo 12, the second mission to land humans on the moon. [The Apollo Moon Landings: How They Worked (Infographic)]

Lifting off atop a Saturn V rocket from Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center, Gordon and his crewmates soared towards space through a storm. Twice in 52 seconds, the Saturn V was struck by lightning, setting off numerous warning lights inside the Apollo 12 spacecraft.

The strikes took the command module's fuel cells offline.

"Fortunately, during launch, procedures say that you have the batteries turned on as a back up system. If we hadn't had those on, we'd have had an automatic abort," Gordon stated. "The batteries picked up the required electrical load and we proceeded from there."

Bean, following quick advice from NASA's Mission Control and remembering an earlier training simulation, was able to bring the fuel cells back online. Once on orbit, the crew completed a check out of their spacecraft's systems and, finding no damage, they were given the go to continue on to the moon.

"If they would have made us come back, we would have been highly upset. The word is 'pissed-off," he said. "Once we saw that the spacecraft... looked to be pretty good, we didn't even contemplate that we were going to come back."

As Conrad and Bean landed the lunar module Intrepid at the Ocean of Storms on the moon, Gordon tended to the command module Yankee Clipper in lunar orbit. He circled the moon alone for 37 hours, 42 minutes and 18 seconds, photographing potential future landing sites.

"If you knew those two other clowns that I lived with, you'd been happy to have a little time alone yourself," he joked. "That's what I always tell everybody. 'Were you sad being alone?' 'Hell no, if you knew those guys, you'd be happy to be alone.'

When Conrad and Bean did return lunar from the surface, Gordon made sure they did not mess up his spacecraft for the journey back to Earth.

"They came back so damn filthy that I wouldn't let them in the command module. I made them strip, take every bit of clothes off they had," he said. "[I] said, 'Holy smoke, you're not getting in here and dirtying up my nice clean command module."

"So they passed the [moon] rocks over, they took off their suits, passed those over, took off their underwear — and I said, 'Okay, you can come in now.'"

The three splashed down in the Pacific Ocean aboard the Yankee Clipper on Nov. 24, 1969, and were recovered by the USS Hornet.

Richard Francis "Dick" Gordon, Jr. was born Oct. 5, 1929, in Seattle, Washington. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from the University of Washington in 1951.

Gordon received his wings as a naval aviator in 1953. He attended all-weather flight school and jet training and was assigned to a fighter squadron in Jacksonville, Florida.

In 1957, Gordon attended the Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Maryland, and served as a flight test pilot until 1960, working on the F8U Crusader, F11F Tigercat, FJ Fury and A4D Skyhawk and he was the first project test pilot for the F4H Phantom II.

Gordon served with Fighter Squadron 121 at the Miramar, California, Naval Air Station as a flight instructor in the F-4H and participated in the introduction of that aircraft to the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. He was also flight safety officer, assistant operations officer, and ground training officer for Fighter Squadron 96 at Miramar.

Winning the Bendix Trophy Race from Los Angeles to New York in 1961, Gordon set a speed record of 869.74 miles per hour (1,399 kp/h) and a transcontinental speed record of 2 hours and 47 minutes.

In total, Gordon logged more than 4,500 hours flying time, 3,500 hours in jet aircraft.

After his selection by NASA but prior to his first spaceflight, Gordon served as backup to David Scott on the Gemini 8 mission in 1966. He similarly served as Scott's backup for Apollo 9 between his own Gemini 11 and Apollo 12 flights, and then again for Scott on Apollo 15 in 1971.

Based on the normal crew rotation schedule, Gordon was expected to command Apollo 18, getting a chance to walk on the moon, but the mission was canceled due to budget cutbacks in September 1970.

In 1971, Gordon became chief of advanced programs for the Astronaut Office and worked on the design and testing of the space shuttle. He left the space agency and retired from the Navy the following year.

Gordon subsequently became the executive vice president for the New Orleans Saints professional football team and later held executive positions at several companies in the oil and gas, engineering and technology industries.

Gordon also volunteered his time as chairman and director of several charitable groups, including the Louisiana Heart Fund, the March of Dimes (Mother's March), the Muscular Dystrophy Association, Boy Scouts of America and Boys' Club of Greater New Orleans, as well as a member of the board for the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation.

He was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in 1982 and in the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in Florida in 1993.

Gordon served as a technical advisor for the 1985 made-for-TV miniseries "Space," based on the novel by James Michener, and appeared as a capcom in Mission Control in two of the episodes. He was later portrayed by actor Tom Verica in the 1998 HBO miniseries, "From the Earth to the Moon."

Gordon is survived by his six children: Carleen, Richard, Lawrence, Thomas, James and Diane from his first wife, Barbara, who died in 2012; his two stepchildren: Traci and Christopher, from his wife, Linda, who died in September 2017; and five grandchildren: Madison, Sean, Ryan, Lea and David.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2017 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.