How Big Would an 'Alien Megastructure' Have to Be?

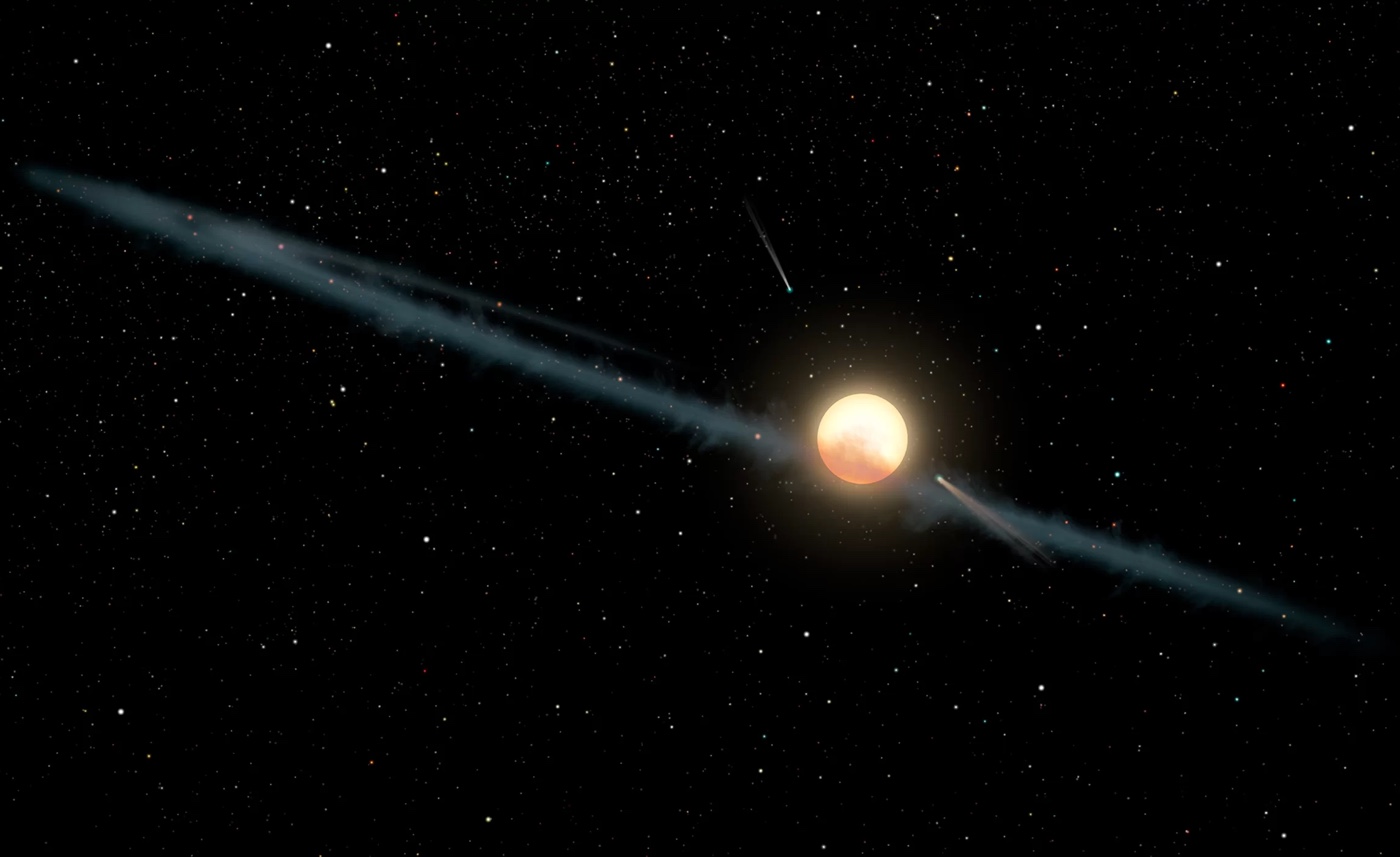

A bizarre flicker of light from space led to the discovery of a still-mysterious star called KIC 8462852, otherwise known as "Tabby's Star," "Boyajian's Star" or the star surrounded by an "alien megastructure."

The star and its weird flicker have been generating headlines since 2015, when the object was first observed. That year, the Kepler Space Telescope, which trails Earth as the planet orbits the sun, was looking for Earth-like planets around thousands of stars when it spotted KIC 8462852.

Ordinarily, a planet that passes in front of a star dims the light reaching Earth from that star, a small dip that recurs at regular intervals. KIC 8462852 didn't have that sort of dimming. For starters, the star dimmed more than it would if a planet were passing in front of it; planets might cut a star's brightness by 1 percent if they are huge, like Jupiter. KIC 8462852's light dipped by up to 22 percent. On top of that, the pattern of changes wasn't regular, as it would be if a planet were passing in front of the star. [5 Times 'Aliens' Fooled Us]

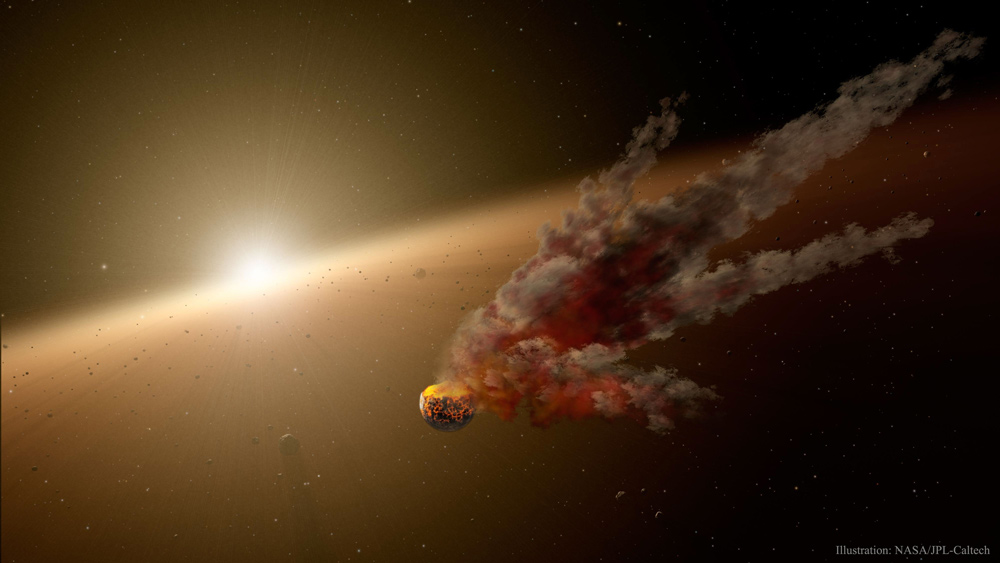

There are several ideas about what the source of the brightness changes could be. Explanations include fragments of comets, a Saturn-like ringed planet or an asteroid field produced as a planet disintegrates. Generally, astronomers don't think it's aliens. And lately, some researchers have proposed that it is an irregularly shaped dust cloud.

Initially, though, some speculated that the star could be harboring a megastructure: a gigantic construction built by an alien civilization that is orbiting around the star. Such a structure could explain the patterns in the star's light. [Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us]

But science-fiction fans want to know — if it was an alien structure, how big would it have to be to create the light-dimming scientists observed? KIC 8462852 is an F-type star, hotter than the sun and about 1,300 light-years away from Earth, where 1 light-year is about 5.9 trillion miles (9.5 trillion kilometers). However, that distance is an estimate, and the star could be as far away as 1,680 light-years and as close as 1,030. The star is about 1.43 times the sun's mass and 1.58 times its diameter — so it's about 1.37 million miles (2.2 million km) across. (To get an idea of how big that is, about the 455 United States, lengthwise, could fit inside this alien megastructure.)

Any structure built around this star would have to be quite large to block the star's light in any noticeable way. Columbia University astronomer David Kipping, who has been searching for exoplanetary moons, estimated that if whatever is passing in front of the star is some discrete object or set of objects, it would have to be on the order of five times the sun's radius, and larger than KIC 8462852 itself.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To put that in perspective, imagine something so big that if it passed between the sun and Earth, the eclipse would last for several days, perhaps weeks, as the structure moved by. The sun's radius is about 432,288 miles (695,700 km). For a structure five times as large — 2.16 million miles (3.4 million kilomters) across It would take 11.6 seconds for a radio signal to travel from one end to the other (it takes 1.3 seconds for such a signal to travel from Earth to the moon).

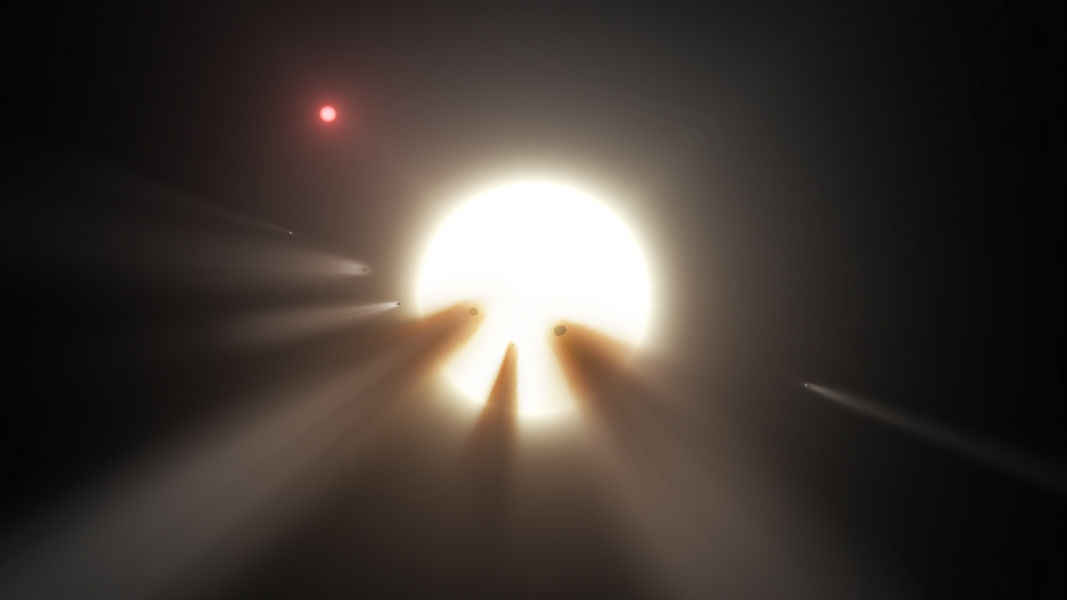

In 1960, physicist Freeman Dyson proposed that a sufficiently advanced civilization could build a sphere around a star and would be able to capture all the star's radiant energy (Earthbound observers would see it re-radiated it as infrared light, so the star would look like a giant heat source). But Tabby's star is clearly not surrounded by a solid sphere, since we can see the star's light. The kind of alien megastructure that one might imagine around this star would be a swarm of small bodies arranged in a spherical formation, or perhaps some large object or set of objects that regularly passes in front of the star. [Dyson Spheres: How Advanced Alien Civilizations Would Conquer the Galaxy (Infographic)]

![By surrounding their star with swarms of energy-collecting satellites, advanced civilizations could create Dyson spheres. [Read the Full Dyson Sphere Infographic Here.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/NJJME58ekYVj7sGjZ4NUz4.jpg)

The latter is called a Dyson swarm, and would be easier to build than a sphere. If the star was surrounded by a Dyson swarm, each satellite would have to be at least asteroid-size, and you'd need many thousands of them. If they are orbiting at distances comparable to our own solar system's inner planets, their periods, or the time it takes them to make one revolution around their host star, would be anywhere from a few months to a few years, following Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

Could Tabby's star be surrounded by a ring-shaped structure a la Larry Niven's "Ringworld" novels? Such a ring, if built around the sun, would have to be about 93 million miles (149 million km) in radius, or about 584 million miles (940 million km) in circumference. That's so large that no known material could survive the stresses; Niven had to come up with a fictional material called scrith. Astrophysicist Katie Mack, told the BBC that you'd need something that was bound more strongly than ordinary molecular bonds. Niven's books posit a Ringworld that is about 1 million miles (1.6 million km) wide, large enough that it would block the light from its parent star if it was in the line of sight of an observer. But the pattern of eclipsing light from Tabby's star doesn't seem to fit what you'd see with a ring; the dimming wouldn't show the irregularities that it does with such a structure, according to Mack.

One could imagine a vast Dyson ring, though, with miles-wide satellites placed at intervals around Tabby's star. But in this case, too, to be at all visible, the satellites would need to be orders of magnitude larger than any space habitat humans have ever attempted to build or colonize, according to Mack — even the ISS is only 368 feet (108 meters) across, and that's far too small to be visible even from as "close" as Mars, let alone light years distant.

The smallest exoplanet that Kepler has found so far is larger than Earth's moon. Called Kepler 37b, it's also a lot closer to Earth than Tabby's star is, only 215 light-years distant. If Tabby's star is surrounded by satellites, they would have to be even bigger than the Death Star from "Star Wars," which is stated in various franchise-related sources as being 60 miles (100 kilomters) across. ['Star Wars' Tech: 8 Sci-Fi Inventions and Their Real-Life Counterparts]

So why don't scientists think aliens are the explanation for the dimming of Tabby's star? One reason is that an alien megastructure would give off radiation in the infrared in a specific way. Any object that gets lit by a nearby star reflects some light and absorbs the rest, and that absorbed light gets re-emitted in a longer wavelength. Basically, objects warm up. In a talk at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute in Mountain View, California, in August 2016, astronomer Jason Wright of Penn State University said studies of the star's light have shown no sign of such "waste heat" with Tabby's star.

The other issue is that such megastructures would be difficult to keep stable. A swarm of satellites orbiting would eventually settle into a disk-like arrangement absent active controls, because any object orbiting another or rotating experiences some centripetal force – this is why the Earth is slightly flattened. The same is true for Dyson rings and swarms. Futurist Anders Sandberg notes on his site outlining Dyson sphere principles that one structure that might stay stable is a Dyson bubble, made of gigantic, miles-square satellites that stay in place because of radiation pressure, in huge solar sails. But to stay in place, those satellites would have to be stationary with respect to the parent star, so they wouldn't cause anomalous dimming over time as was seen with Tabby's star.

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.