Making a Moon Base With 'Artemis' Author Andy Weir

In Andy Weir's "Artemis" (Crown, 2017), the lead character is drawn into a crime caper on a lunar city. Weir is known for "The Martian" (Crown, 2014) which described in realistic detail how someone would survive being stranded on Mars. In "Artemis," Weir brings a similar realism to the moon as the ultimate tourist destination.

"Artemis" was released today (Nov. 14) as a novel and audiobook featuring Rosario Dawson.

Space.com talked with Weir about the world of "Artemis"; creating its lead character, Jazz; and how "the moon is basically made of moon bases, with some assembly required." [How Moon Bases and Lunar Colonies Work (Infographic)]

Space.com: Can you talk about how the idea for "Artemis" first developed?

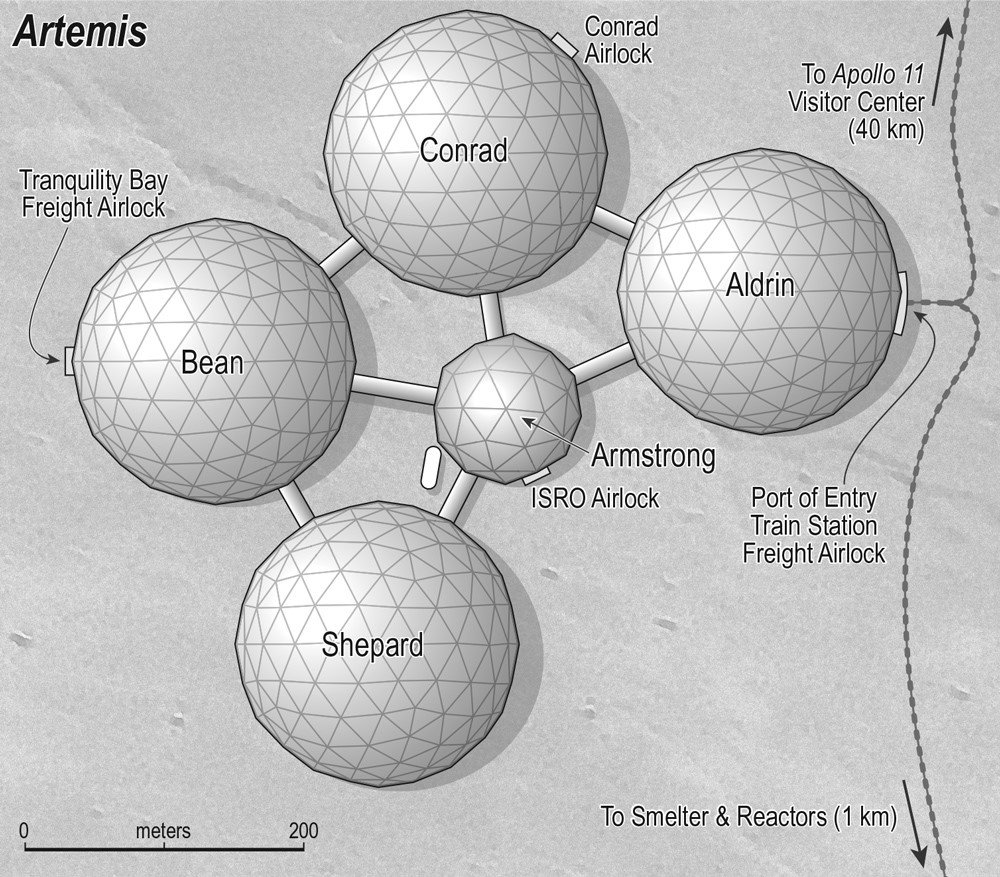

Andy Weir: I wanted to design a city on the moon. I wanted to come up with a city on the moon and a reason for there to be a city on the moon. I came up with the city and how it was built and what its economic foundation was and everything long before I came up with the story or characters to take place in it. I guess that's kind of — world-building and making settings is fun. The actual writing part is no fun. That's kind of where the original idea came from.

Space.com: What kinds of stories did you try to set in that city before you finally settled on one?

Weir: I went through a few revisions. "Artemis," as it is right now, was kind of my third attempt at a story, and that's the one that stuck. The first two revisions just weren't very good. I may steal elements of them someday, so I'm not really telling people what they are. But in the first revision, Jazz — who is the main character in "Artemis" — Jazz was a very minor, tertiary character. I just needed a comedy smuggler type, and so I invented her for that. And I didn't like the plot that had developed, and in the next revision of story, Jazz was much more prominent, but still not the main character, and then I realized, well, the fun part here is Jazz anyway, so why not write a story about her? So that's how I landed on the current plot.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: What drew you to writing about Jazz in particular?

Weir: In every version and as it went forward, she was the one who got all the funny lines. She's the smart-ass. She's kind of the lovable rogue archetype. I really like that type of character, and so I had fun writing her.

Space.com: How did you come up with the technology that made a moon base possible?

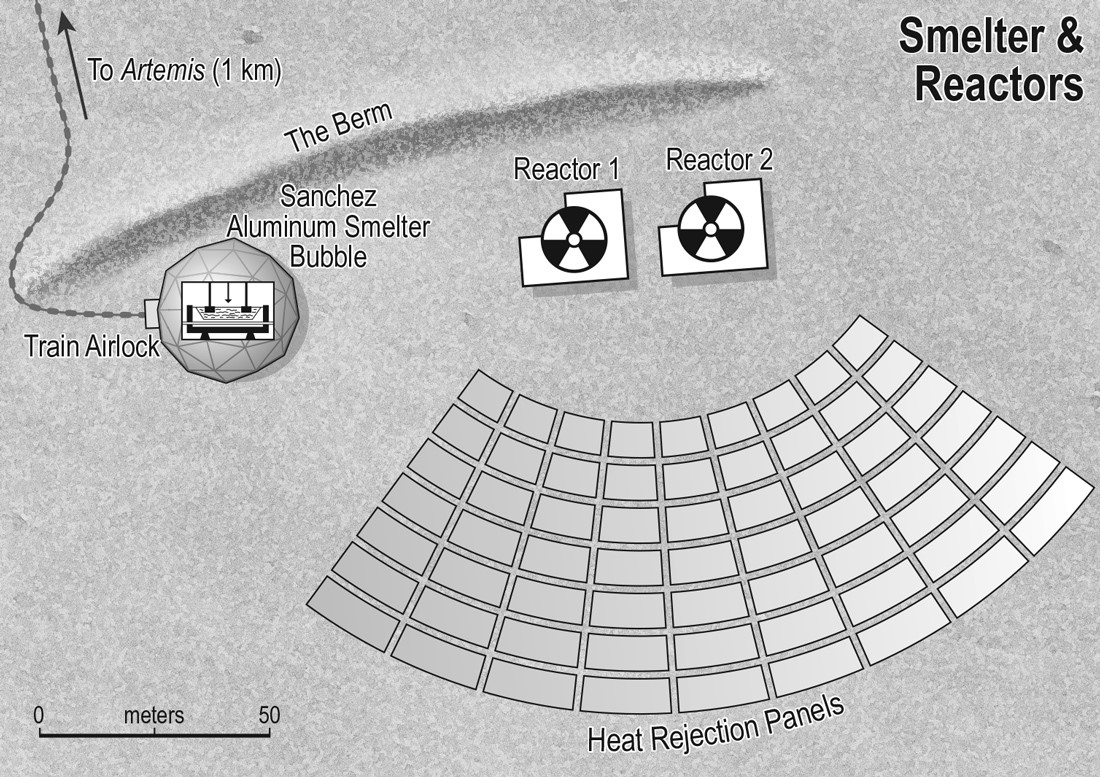

Weir: The cool thing is, everything in "Artemis" is actually technology that already exists. Really, it was more research than developing technology, although trying to figure out the most efficient way to build a city on the moon was kind of cool. Like, how do you build a city on the moon when you want to absolutely minimize the amount of mass you send to the moon. Well, cities are big, and they weigh a lot, so you're going to want to make the city with materials that are present, not ship it over in its entirety. That's why they would smelt the anorthite [the material the lunar highlands are made of] into aluminum, and that also gives you oxygen.

It's really cool, actually — the moon is basically made of moon bases, with some assembly required. In the lunar highlands, which is the part of the moon that is not smooth — if you look at the moon, you see the smooth parts and the bumpy bits. The lunar highlands are the bumpy bits — 85 percent of the rocks just lying around on the ground are anorthite, which is a mineral, and you can smelt that into aluminum, oxygen, silicon and calcium. That gives you aluminum to make your moon city out of and oxygen to fill it. And by the way, if you want glass or windows, it also gives you silicon, and there's a bunch of oxygen still. Silicon and oxygen makes glass, and — yeah. It's really cool. It's like it's just there, just waiting for us. If we could just get there.

And so, the conceit of the story is that the commercial space industry has driven the price of low-Earth orbit down to the point that middle class people can afford to go to space. And Artemis' economy is based on tourism. For me, one thing is when I'm reading a book I get hung up on the economy of fictional environments. I'm like, wait a minute, why does this city exist? Why would people live there? Why wouldn't they go somewhere else? Stuff like that. For a lunar city, the thing I came up with was tourism. If middle class people can afford to go to the moon, even if they had to get a second mortgage to afford it, I think a lot of people would.

Space.com: And you calculated exactly how much it would cost, given those conditions, to transport objects and people to the moon, and therefore developed what the society there would be like.

Weir: I came up with this whole economic thing — I actually wrote a paper on it, and we're going to try to get that out there via an outlet later.

I don't describe any of that in the book; that's what I came up with in advance. What we learned from "The Phantom Menace" — don't start a science fiction story with a description of supply-side economics. But it's important to me that that work out.

Space.com: Would you rather live on the moon or Mars, assuming both of them had equivalent infrastructure?

Weir: I'd rather live on Earth, all things considered. I write about brave people. I'm not one of them. If I had to choose between the moon or Mars, I would choose the moon, even if they had the same infrastructure, if they both had cities and stuff. Just on the grounds that the moon is still safer, because if things go really, really bad, you can leave and go to Earth. On Mars, if things go bad, you're on your own.

To put it in perspective of how much further away Mars is than the moon, imagine you're on a football field, and you're at one goal line and Mars is at the other goal line. The moon would be about 4 inches [10 centimeters] in front of you. [Dazzling 'Museum of the Moon' Exhibit Celebrates 'Artemis' in NYC]

Space.com: How was the experience of writing a different lead character and voice than "The Martian"?

Weir: Well, I still got to use the first person, smart-ass narrative style, so it wasn't that big a change. I guess the real change was — first off, I did my best at writing a female lead, but in the end, I'm not a woman, so I'm sure there's lots of places where she ends up sounding like a guy. I ran it by as many women as I could, in my inner circle, people I can trust with a manuscript before it releases, and got feedback from all the women, and gave it my best shot.

And also, Jazz is a much more nuanced and flawed character than Mark Watney. Mark Watney — you can't help but like him, he's just this guy that's in a terrible situation that's not really his fault, whereas Jazz's problems are mostly self-inflicted. She's made a lot of bad decisions, and makes additional bad decisions during the book. The way I like to say it is, Mark Watney is based on the idealized version of me. He's everything I wish I were. He has the qualities of myself that I like and none of my many flaws, and he doesn't have any of my neuroses. Jazz is a little bit more like the real me. Flawed, has bad decisions in her past, makes mistakes. Smart, but doesn't always apply that correctly. Jazz is actually a lot more like the real me, so it's always kind of sad when I read a review that says, "Oh, I didn't like Jazz much." I'm like, "Awww."

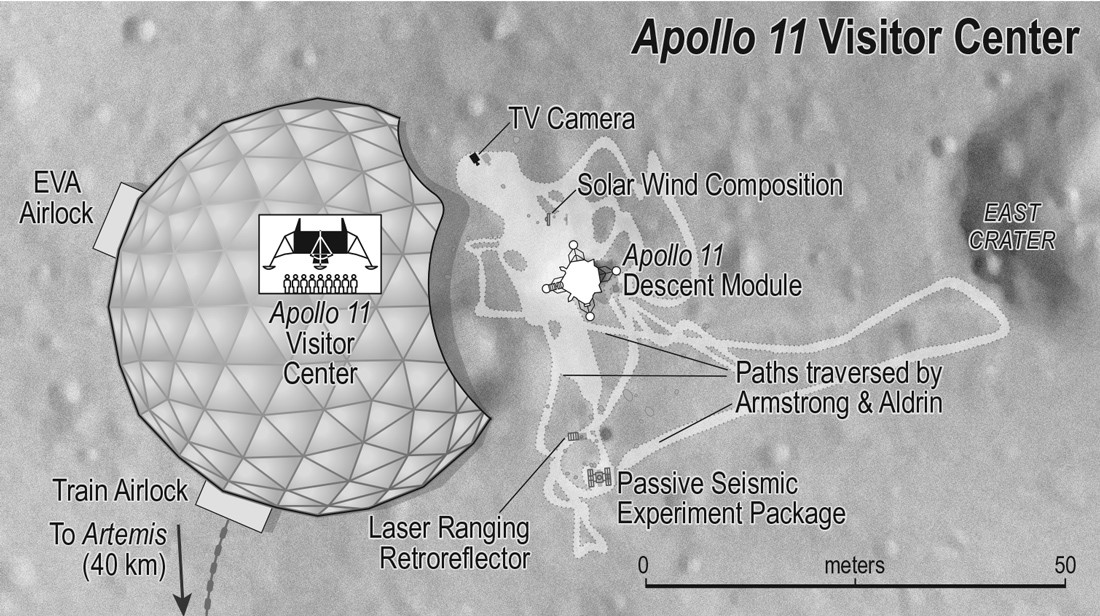

Space.com: I also wanted to talk about those crazy "hamster balls" visitors can use to tour the Apollo 11 landing site.

Weir: It'd be fun, wouldn't it?

Space.com: How did you think of those?

Weir: I was trying to think about, how could you have a completely untrained person do an EVA [extravehicular activity, or spacewalk]. And then I came up with the hamster ball idea and said on your backpack is a thing that manages the air inside the ball. And there's a little bit of fictionalization in there in that I'm not sure what that ball is made of, but it can hold in a fifth of an atmosphere, and it's clear, and it's flexible.

But you've got to get into it and seal it somehow. It just seems like that would be an awesome thing, because you have the freedom of movement. Basically, I don't think that an untrained person, like a tourist or something, could handle being in an EVA suit. First off, it's really clunky, and it takes astronauts months and months of training to learn how to move at all in them, and it's like, you can't scratch your face. It's really inconvenient. But here, they'd have the freedom of motion of their own human body, and then they can do whatever they like in the ball. [Evolution of the Spacesuit in Pictures (Space Tech Gallery)]

Space.com: Assuming you were already on the moon, would you go out in one of those?

Weir: Yeah … I guess if I was already there. I'd be like, eh, you know…

Space.com: How does world-building and plot fit together when you're writing something like "Artemis"?

Weir: I started with the world-building and said, "OK, this is the world it takes place in, and I'm not really willing to change the world to save the plot, except for if I can come up with something incredibly awesome. For the most part, I'm just like, well, here's the problem, and here's what they're doing, and here's the setting. Now what?

Ultimately, [the city] Artemis … lends itself to all this interesting stuff, [and that's] actually not because it's on the moon, but because it's so far away from everything else. You could have similar plots just take place on an isolated island in the Pacific or something like that, where basically help is too far away, and there's really no infrastructure in place for strong authorities.

I think that's one of the main reasons Artemis ends up with these avenues of excitement. Human civilization is all about getting rid of those. OK, in order to prevent our entire city from being destroyed, we're going to make fire departments, police departments — so we do. But frontier towns don't have that luxury, so that's where the interesting stuff happens.

This interview was edited for length. You can buy "Artemis" and its audiobook on Amazon.com.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.