NASA Will Launch E. Coli into Space to Study Antibiotic Resistance

Update for Nov. 12: The Cygnus cargo mission carrying this experiment launched on Sunday, Nov. 12. Its planned launch attempt on Nov. 11 was aborted when a wayward aircraft entered the restricted airspace near the launch site.

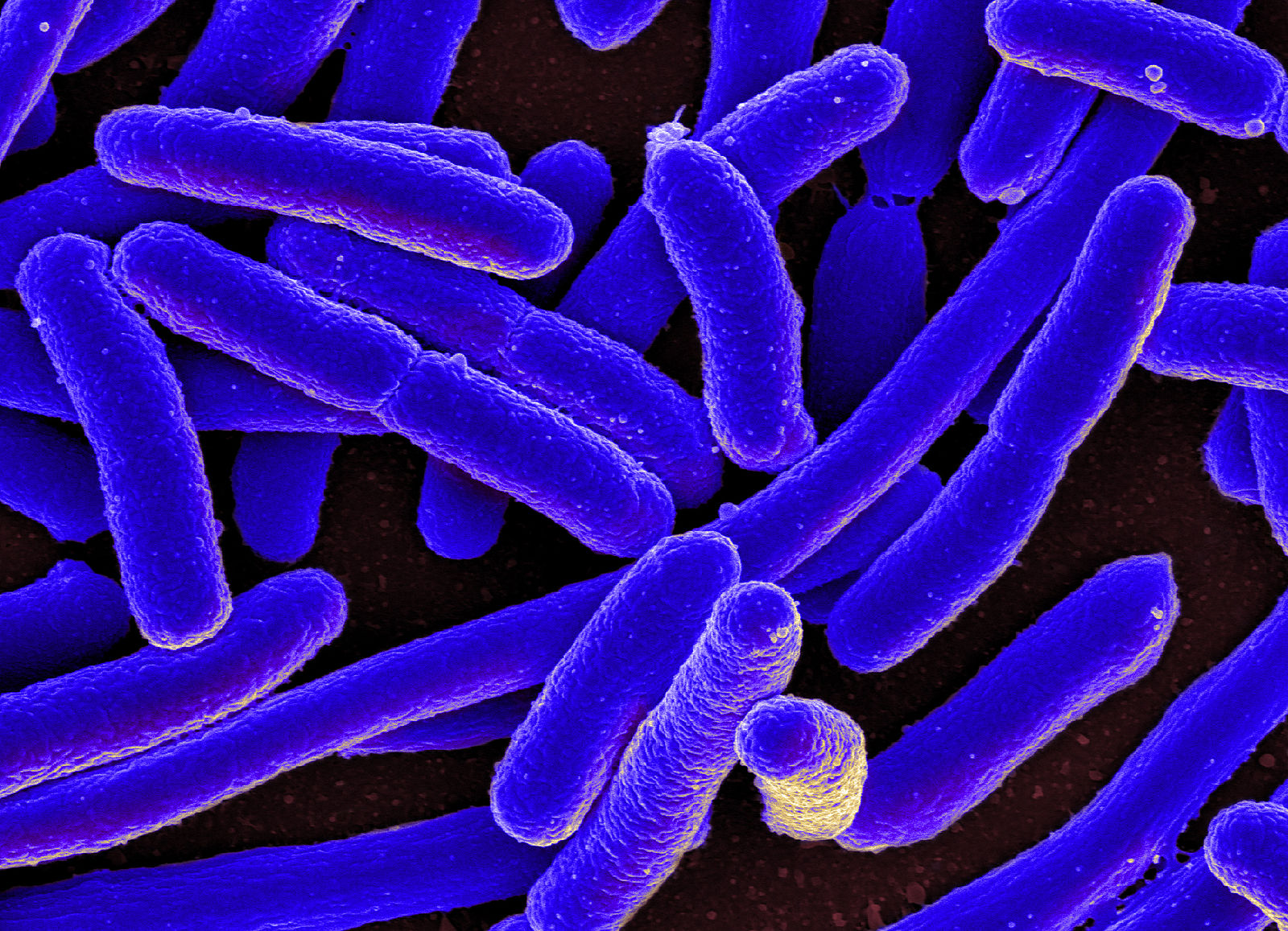

E. coli, a common bacterial pathogen responsible for millions of urinary tract infections and foodborne illnesses every year, will blast off to the International Space Station (ISS) on Saturday (Nov. 11) to take part in a study of antibiotic resistance.

The E. coli AntiMicrobial Satellite (EcAMSat) mission is scheduled to launch to the ISS on Orbital ATK's Cygnus cargo spacecraft at 7:37 a.m. EST (1237 GMT) along with a slew of other science experiments and supplies for the Expedition 53 crew. You can watch the launch live on Space.com, beginning at 7 a.m. EST (1100 GMT), courtesy of NASA TV. [Preview: Weird Science Experiments Launching to Space Station Early Saturday]

After the E. coli samples arrive at the ISS, the experiment will examine how microgravity affects the bacteria's ability to thrive while exposed to antibiotics. Since humans started using antibiotics in the mid-20th century, pathogens like E. coli have evolved new genes that make them increasingly resistant to antibiotics.

"EcAMSat will investigate spaceflight effects on bacterial antibiotic resistance and its genetic basis," NASA officials said in a statement. "Bacterial antibiotic resistance may pose a danger to astronauts in microgravity, where the immune response is weakened. Scientists believe that the results of this experiment could help design effective countermeasures to protect astronauts' health during long-duration human space missions."

Here on Earth, this study could help medical researchers better understand how bacteria respond to stress, which may lead to the development of more effective antibiotics, according to the statement.

The investigation aims to determine "the lowest dose of antibiotic needed to inhibit growth of Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacterial pathogen that causes infections in humans and animals," NASA officials wrote in a description of the experiment.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

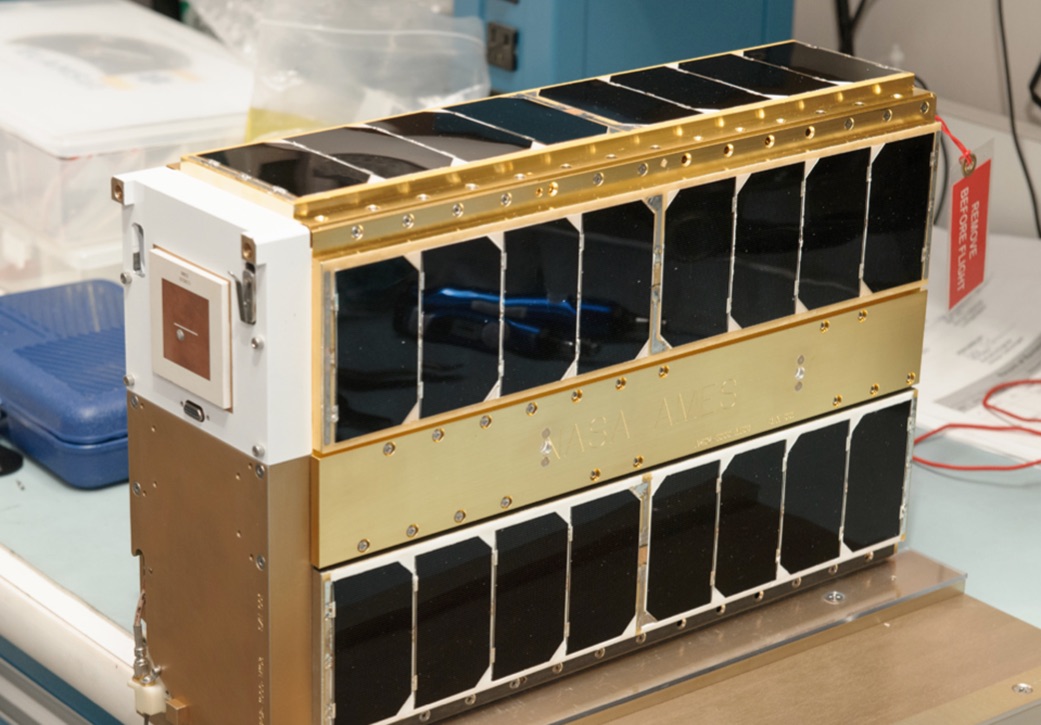

Rather than being housed inside the space station, this experiment will take place in a 6U cubesat, a small satellite that has six times the volume of a single cubesat. EcAMSat's satellite weighs about 23 lbs. (10.4 kilograms) and measures 14.4 inches (36.6 centimeters) long, 8.9 inches (22.6 cm) wide and 3.9 inches (9.9 cm) tall.

The NanoRacks CubeSat Deployer at the International Space Station will send the bacteria on their way, and the experiment will be conducted autonomously inside the cubesat.

Both naturally occurring and mutant strains of E. coli will be exposed to different concentrations of antibiotics. "The overall purpose of this is to challenge these bacteria to different stress levels that will be controlled autonomously through software," Stevan Spremo, the EcAMSat project manager at NASA's Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley, California, said during a teleconference with reporters.

Then the bacteria will be stained with a special type of color-changing dye, "which changes from blue to pink when enzymes generated by cellular metabolic processes act upon it," NASA's description reads.

In other words, the bacteria that appear pink after being doused in the "viability dye" were resistant enough to survive the antibiotic treatment – specifically, an antibiotic called gentamicin, Spremo said. "Thereafter, we'll look at the trends and be able to decipher what stress response has occurred due to the targeted gene that we're looking at — rpoS — and the absence of it," he added.

"If we see the stress response with this gene as an indicator of what's going on with antibiotic resistance, we may be able to increase the effectiveness of antibiotics as well her future use both in spaceflight and on the ground," Spremo said, adding that E. coli is known to be more virulent in space than on Earth.

The EcAMSat experiment is a joint effort between NASA's Ames Research Center and the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.