Thanksgiving Night Sky 2017: Saturn, Mercury (& the Moon) On the Menu

Thanksgiving is often thought of as a time for family and friends to get together — but after the feast has been consumed, what's next on the agenda? A time to reflect on one's many blessings?

Certainly.

A visual feast of football enjoyed from an overstuffed recliner, long after the turkey and all its trimmings have been savored and devoured?

Perhaps.

But if the big gathering is at your home this year, here is a concept that's a bit outside the box: Why not break out your telescope and treat your loved ones to an eyeful of celestial sights? Have a star party, and introduce your guests to the night sky. That certainly can make this year's Thanksgiving stand out, as well as provide some great fun. [The Brightest Planets of November's Night Sky]

Most folks usually settle into their holiday meals by midafternoon, and this time of year, your guests won't have to wait long thereafter before the sun sets and they're under the cover of darkness. Assuming that your skies are cloud-free, what are a few "gee-whiz" objects that you can point your scope at?

Two planets to start

About 45 minutes after sunset, look low toward the southwest horizon. Make sure there are no tall obstructions, like nearby trees or buildings. Look for a bright, orange-yellow "star" just above the horizon. That will be Mercury, the closest planet to the sun. And straight above Mercury will be another star-like object, shining about half as bright as Mercury and glowing with a somewhat sedate, yellow-white glow. That's Saturn, the planet adorned with a magnificent set of rings.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Of course, everyone will want to see both planets through your telescope, especially Saturn! You'll need an eyepiece that magnifies at least 30 power to clearly bring out the rings. If you own a 4-inch (10 centimeters) telescope, it's best to use 100 power; with a 6-inch (15 cm) instrument, try a magnification of 150 power. But before the first person steps up to get a look, make sure you make the following disclaimer: Both planets are currently very low, and because the atmosphere disturbs observations of lower objects more, they may very well appear rather distorted through your telescope. Especially near the horizon, the air is always in commotion; warm and cold currents are mixing together, causing the scenery beyond to blur and quiver. If that's the case on turkey night, then tell your guests that if they want to get a better view of the "Lord of the Rings," you can make a date to assemble again next spring or summer, when Saturn will appear higher and offer a much steadier, clearer and more satisfying view. [Best Telescopes for the Money - 2017 Reviews and Guide]

But in any case, be sure to throw out a few interesting facts about these two worlds. Tell them, for instance, that the temperature on the side of Mercury that is facing the sun is twice as hot as the inside of the oven that cooked your turkey: about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (427 degrees Celsius). Or perhaps a few of your holiday guests traveled a long distance to get to your house. So tell them that right now, that dot of light that we see as Saturn is over a billion miles from Earth. And if they traveled at 65 mph (105 km/h), it would take them about 641,000 days — or about 1,755 years — to get there!

Suddenly, that long trip to get to and from your house in holiday traffic doesn't seem all that long.

A little "luna-see"

Of course, there will be one object that everyone will want to see through your telescope. That object will be roughly a quarter of the way up from the south-southwest horizon at dusk and will remain in view until nearly 9 p.m. on Thursday night.

It's our nearest neighbor in space: the moon.

On Thursday night, it will appear as a wide crescent, about 24 percent of its surface illuminated by the sun, nearly five days after having passed the new moon phase, or the beginning of a new lunar cycle, which astronomers call a lunation. Be sure to ask if anyone can see its whole round disk dimly illuminated with a grayish-blue light. Tell your guests that if they were astronauts spending Thanksgiving on the lunar surface and looking up at the sky, they would see our Earth shining among the stars in their sky. And like the moon, our Earth would appear to go through phases, but opposite to those of the moon. Astronomers call that phenomenon "complementary phases."

So from the moon, we would see our home planet as a bluish gibbous disk, 76 percent illuminated, four times larger than the moon and about 50 times as bright. It is that nearly full Earth that shines on the dark part of the moon at its crescent phase, flooding the darkened lunar landscape with enough light to make the whole disk visible to us. This phenomenon is known as Earthshine, though many have called such a sight "The old moon in the new moon's arms." And when you look for Earthshine, note that the illuminated part of the moon, because it is brighter, seems larger than the rest of the disk.

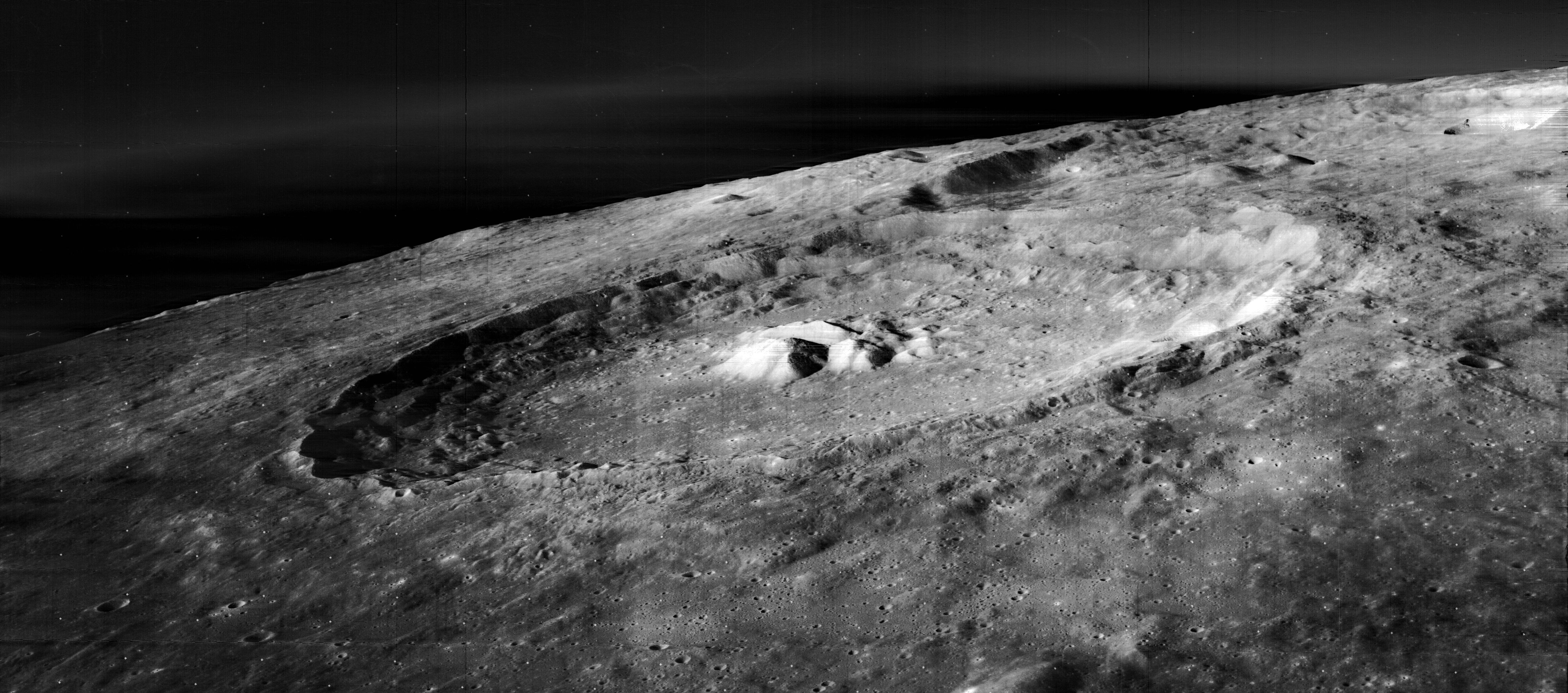

And using your telescope, you'll also be able to watch a lunar sunrise happening over a large crater. [Gorgeous Glow! The Crescent Moon and Earthshine (Photo)]

Sunrise at Theophilus

Check out the line that separates light from dark on the lunar surface. That line is called the terminator. On the right of this line, the sun is shining; on the left, it is night. Through the telescope, that sunrise line appears far from straight, for it is passing over a pretty rough landscape. The craters and mountains on the moon are easy enough to see, especially those along the terminator. There, the light comes from the side, the mountains and crater rims cast long shadows and the brightly lighted peaks stand out in bold relief against the shadows. When the terminator moves on — when the sun climbs higher in the sky over the region we are watching, and as the shadows grow shorter — the lofty mountains seem to melt into the landscape and practically disappear.

On Thanksgiving night, appearing roughly midway along the terminator, the magnificent crater Theophilus will immediately catch your eye. Observers in the eastern U.S. will see it emerging into view at around 5 p.m., but it will be much more noticeable a couple of hours later. On the West Coast, Theophilus will already be in full view at dusk and will be even more evident a couple of hours later, as the terminator slowly advances across the moon at 10 mph (16 km/h). With a diameter of about 60 miles (100 km) and a depth of about 10,500 feet (3,200 m), the crater's interior appears entirely black on Thursday night, except for a pinpoint of light that marks the summit of a large cluster of central mountains.

Final views, then a snooze

You can finish your tour of the sky by pointing out some of the landmarks of late autumn: the Great Square of Pegasus, almost overhead; the "M" of Cassiopeia, high in the north; and the stars of the Big Dipper, (also known as Ursa Major, the Big Bear), down low, just scraping the northern horizon. This time of year, bears are hibernating, which is why our celestial bear is so low in our sky.

And that could also be the signal to head back inside and, like the bears, finish the day with a post-Thanksgiving nap.

Remember, Thanksgiving is a time to be merry, a time to say thank you — and a time to have some great fun.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon Fios1 News, based in Rye Brook, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.