Quirky Comet Has Unexpected Composition, NASA Study Shows

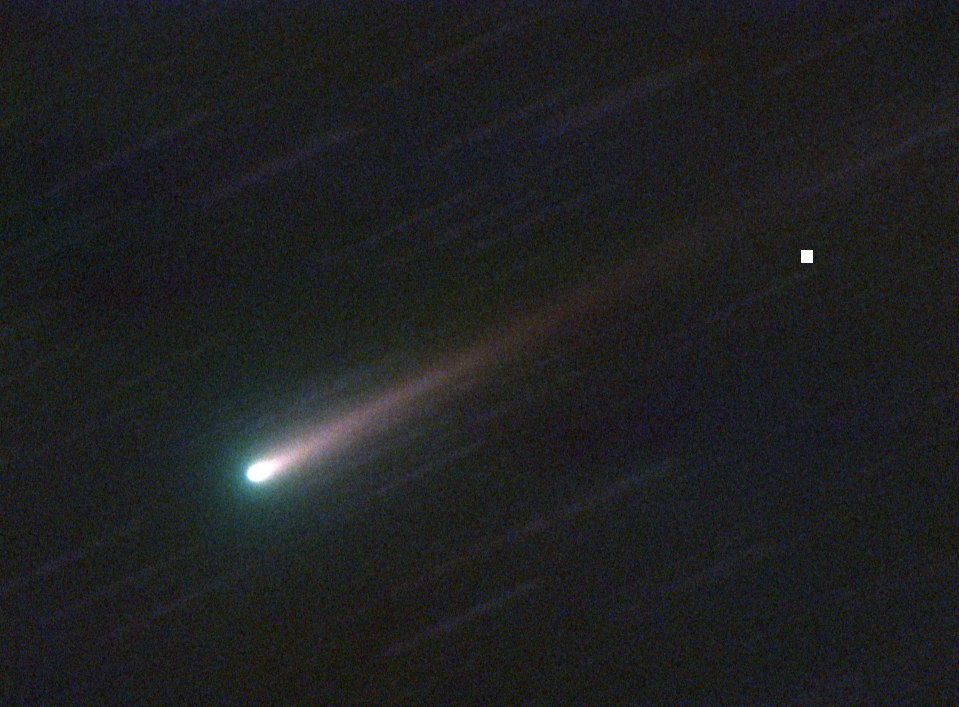

A strange green comet that zoomed past Earth earlier this year is unlike any other comet observed to date, according to new NASA research.

The comet, officially known as 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdusakova, belongs to the Jupiter family of comets, which travel to the inner solar system every five to seven years. During its most recent flyby in February, comet 45P passed just 7.4 million miles from Earth.

Using NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) in Hawai'I, researchers studied the icy body up close. The observation unveilied key details about the native ices in Jupiter-family comets, which lie relatively close to the sun but are less well-understood than the long-period comets that hail from the distant Oort Cloud at the outskirts of the solar system, according to a statement from NASA.

"This research is groundbreaking," Faith Vilas, the solar and planetary research program director at the National Science Foundation, which helped support the study, said in the statement. "This broadens our knowledge of the mix of molecular species coexisting in the nuclei of Jovian-family comets, and the differences that exist after many trips around the sun."

As Comet 45P flew by, the researchers measured the levels of nine gases, including water, carbon monoxide and methane, which were released from the icy nucleus into the comet's thin atmosphere, known as the coma, according to the statement.

"Several of these gases supply building blocks for amino acids, sugars and other biologically relevant molecules," NASA officials said in the statement. "Of particular interest were carbon monoxide and methane, which are so hard to detect in Jupiter-family comets that they have only been studied a few times before."

The gases released from the comet originate from ices, rock and dust. Understanding the composition of these materials helps researchers learn more about how the comet formed and evolved, according to the statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Comets retain a record of conditions from the early solar system, but astronomers think some comets might preserve that history more completely than others," Michael DiSanti, an astronomer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the study, said in the statement.

The IRTF is able to distinguish the chemical fingerprints of native ices in the coma using its iSHELL high-resolution spectrograph, which also allows researchers to observe many comets that may otherwise be too faint, the researchers said.

The IRTF observations were collected in early January 2017, soon after 45P made its closest approach to the sun. The researchers compared levels of the native ices on the sun-drenched side of the comet to the shaded side, showing small amounts of frozen carbon monoxide, but an unusual amount of methane.

"By itself, this wouldn't be too surprising, because carbon monoxide escapes into space easily when the sun warms a comet," officials said in the statement. "But methane is almost as likely to escape, so an object lacking carbon monoxide should have little methane. 45P, however, is rich in methane and is one of the rare comets that contains more methane than carbon monoxide ice."

A possible explanation could be that the methane is trapped inside other ice and, as a result, is not readily released from the comet. However, the researchers also found "larger-than-average" amounts of frozen methanol, suggesting that the carbon monoxide may have reacted with hydrogen to form methanol at some point in the comet's past.

"Comet scientists are like archaeologists, studying old samples to understand the past," said study co-author Boncho Bonev, an astronomer at American University. "We want to distinguish comets as they formed from the processing they might have experienced, like separating historical relics from later contamination."

Their findings were published Nov. 21 in the Astronomical Journal.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.