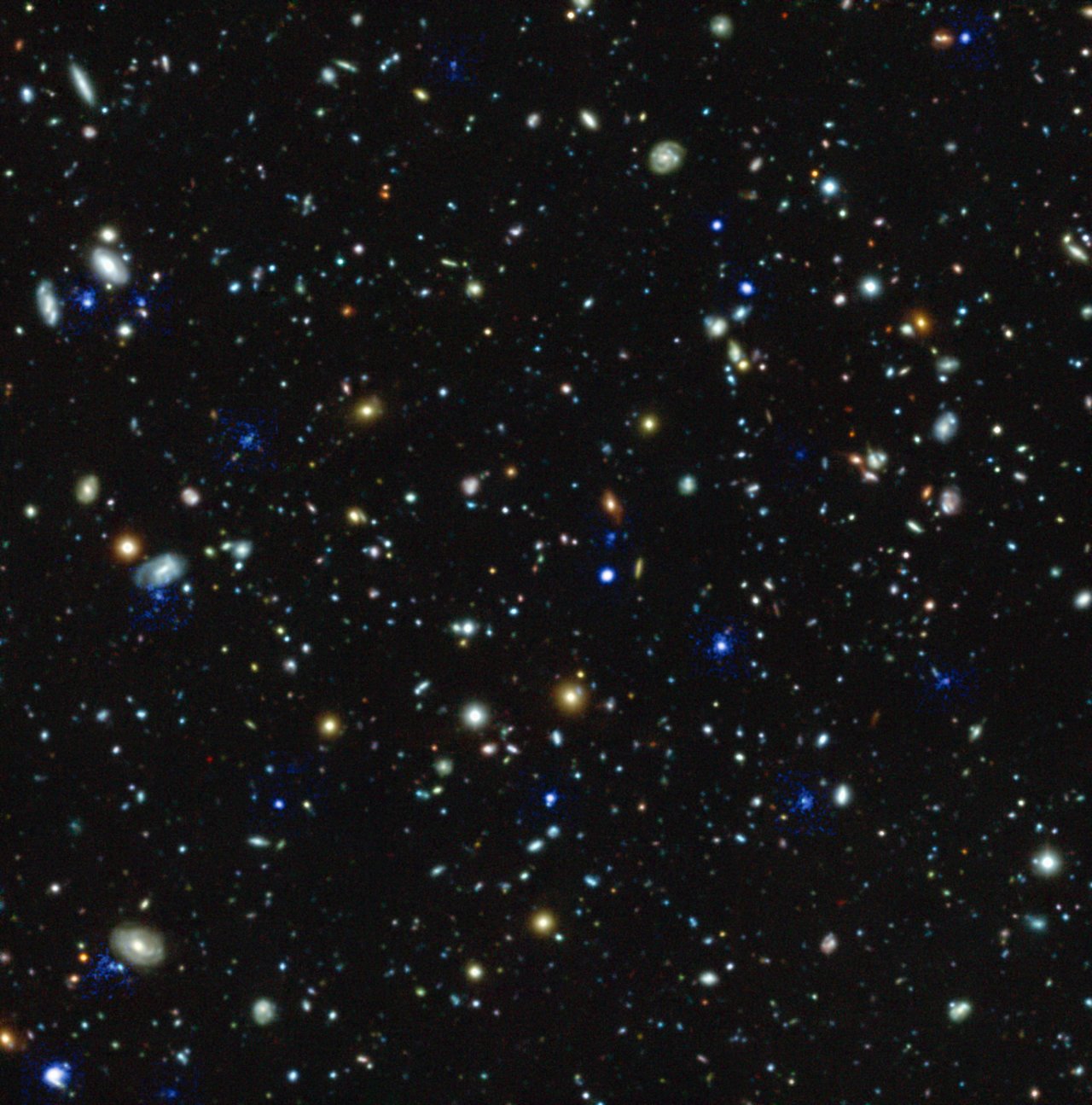

Found Them! 72 Unseen Galaxies Found Hiding in Plain Sight

Astronomers have found 72 potential galaxies hiding in plain sight inside a vast patch of the sky previously observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. The discovery not only gives astronomers new targets to study, but also will aid studies of star motion and formation and other properties of old galaxies, the researchers said.

The new study was performed by the MUSE instrument on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile. Astronomers discovered the newfound galaxies while measuring the distances and properties of 1,600 galaxies captured by the Hubble Space Telescope during its Ultra Deep Field survey.

The 72 newfound galaxies shine in Lyman-alpha light, which is a particular wavelength of ultraviolet light. Because the galaxies are receding from us, their wavelength was stretched from ultraviolet to visible, or near-infrared. [26 Stunning Photos from the Hubble Ultra Deep Field]

The discoveries were made in the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, which is a tiny region of the sky in the southern constellation Fornax (the Furnace). The Hubble data were originally obtained in 2004, two years after NASA space shuttle astronauts visited the space telescope to install the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and perform other needed maintenance.

Using ACS, Hubble peered at a small region of the sky and found galaxies that had formed less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang, which kick-started the universe. (The Big Bang took place about 13.8 billion years ago, making those galaxies more than 12.8 billion years old.)

"MUSE can do something that Hubble can't — it splits up the light from every point in the image into its component colors to create a spectrum. This allows us to measure the distance, colors and other properties of all the galaxies we can see — including some that are invisible to Hubble itself," stated Roland Bacon, who led the survey team and is also an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics Research of Lyon at the University of Lyon in France. [From the Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

MUSE is a spectroscopic instrument, meaning it measures light emitted, absorbed or scattered in space. Using spectroscopy, astronomers can learn about stars, galaxies and other objects, including properties such as how fast the objects are moving and what elements they are made of. MUSE recently underwent an adaptive-optics upgrade, which could help with future studies of old galaxies, Bacon added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new work resulted in 10 science papers that will be published in a special issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

"MUSE has the unique ability to extract information about some of the earliest galaxies in the universe — even in a part of the sky that is already very well-studied," stated Jarle Brinchmann, lead author of one of the papers.

"We learn things about these galaxies that [it] is only possible [to learn] with spectroscopy, such as chemical content and internal motions — not galaxy by galaxy, but all at once for all the galaxies," added Brinchmann, who is an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands and the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences at CAUP (Center for Astrophysics of the University of Porto) in Portugal.

Astronomers also found hydrogen halos in old galaxies, which could provide more information about how material leaves and enters galaxies formed early in the universe's history. Future research directions could include looking at star formation, galactic winds, galaxy mergers or even a phenomenon known as cosmic reionization.

That phenomenon explains how light returned to a dark universe billions of years ago. "First light" in the universe was roughly 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the cosmos cooled down and fundamental particles were able to combine into atoms. However, once these combinations ceased, the universe entered a dark age, because there was no other light available — the first stars weren't shining yet. Reionization occurred between 150 million years and 650 million years after the Big Bang, when the first stars and galaxies were formed from collapsing groups of gas, producing light in the universe again.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.