December Lights: 6 Super Facts for the Geminid Meteor Shower

Introduction

Get your winter coats ready for the Geminid meteor shower, the bright, mid-December light show that's one of the best of the year. In 2017, the peak runs from the night of Dec. 13 to the morning of Dec. 14 — but in the meantime, here are six super facts about the upcoming shooting stars. [Geminid Meteor Shower 2017: When, Where & How to See It]

Top meteor rates

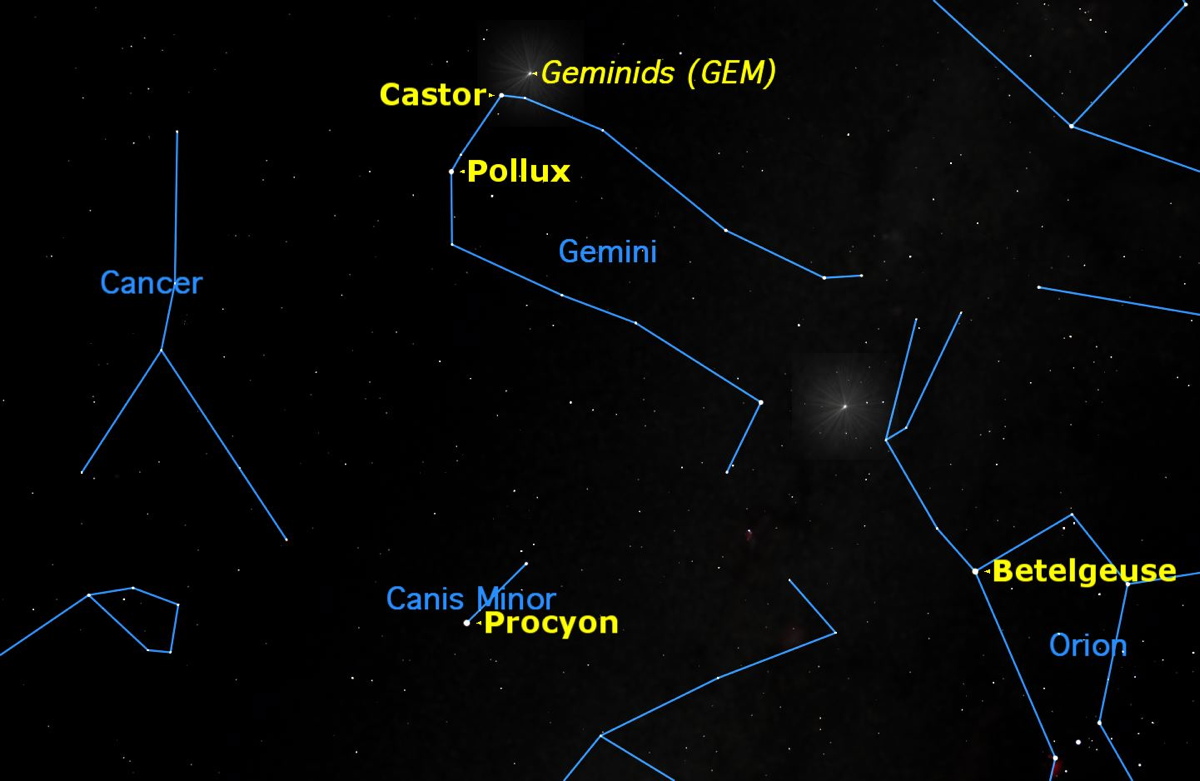

The Geminid meteors are bright, so skywatchers can spot as many as 120 of the objects streaking by per hour in dark skies. This happens as pieces of dust and debris burn up in Earth's atmosphere. The meteors appear to radiate from the bright constellation Gemini, but they can appear all over the sky! In fact, meteors farther from Gemini are likely to have longer tails and be easier to spot.

Sunny visitor

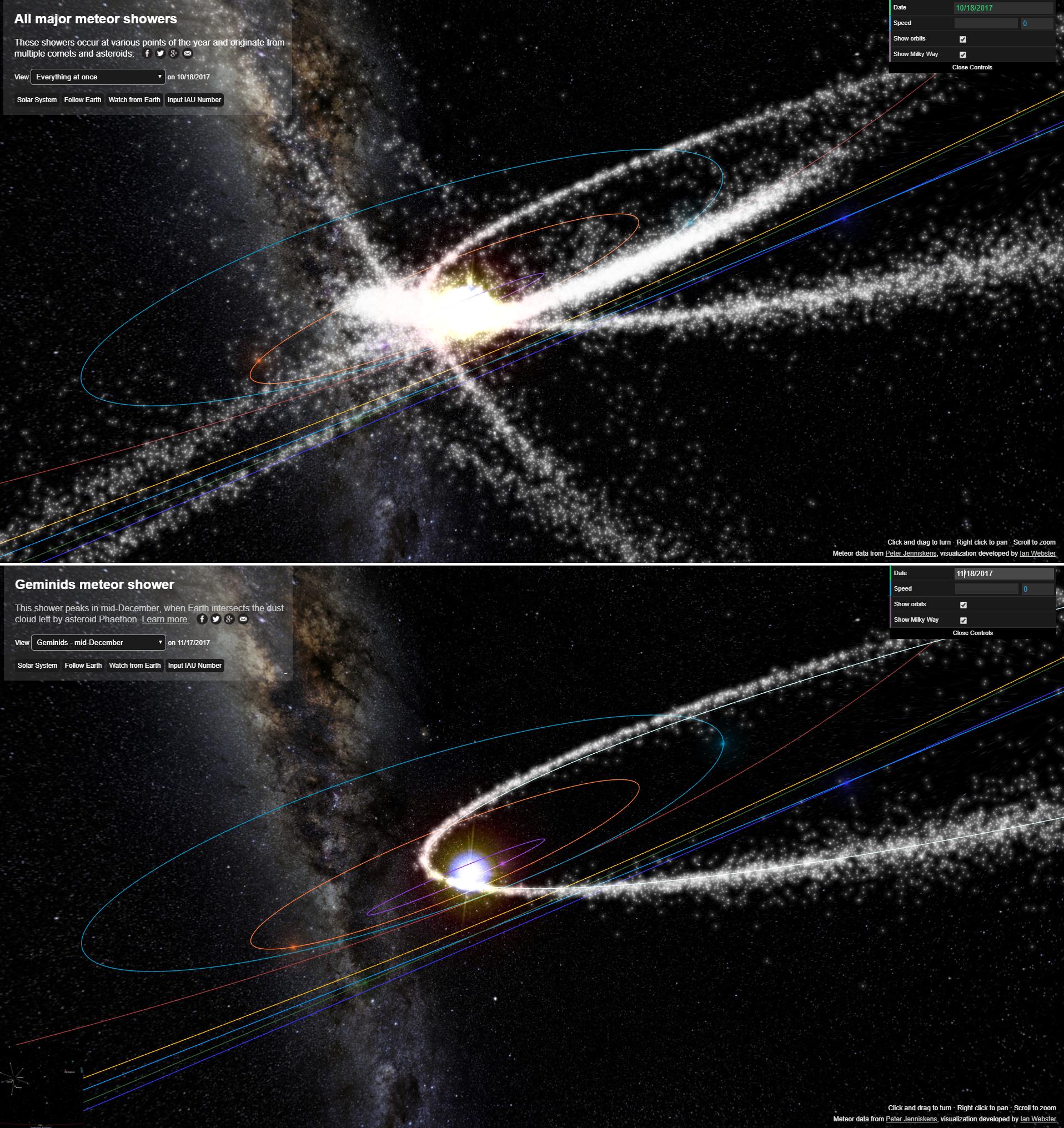

The meteor shower is caused by dust and debris strewn in the path of the asteroid 3200 Phaethon, which itself orbits Earth every 1.4 years. The asteroid passes within 13 million miles (21 million kilometers) of the sun on each orbit, 14 percent the distance between Earth and the sun. This earned the space rock the name Phaethon, after the Greek sun-god Helios' chariot driver.

200 years old

The Geminids were first spotted almost 200 years ago; the first recorded observation came in 1833 from a riverboat on the Mississippi River. But at the time, only 10-20 meteors per hour could be seen. [How to See the Best Meteor Showers of the Year]

Getting stronger

Since the meteor shower's discovery, it has steadily gained strength — from 10-20 meteors per hour to around 120 visible per hour today. Researchers say that Jupiter's gravity has pulled the asteroid's stream of dust and debris closer to Earth, which means our planet hits more debris, creating a more spectacular show. Enjoy it now — it's possible that Jupiter's gravity will disturb the path enough that it travels out of Earth's orbit altogether someday.

Asteroid mashup?

Why the sudden start to the meteor shower 200 years ago? One theory holds that 3200 Phaethon crashed into another space rock, causing the outpouring of debris that produces the meteor shower today. That collision would have produced a trail of dust that wasn't noticeable from Earth until Jupiter tugged the asteroid into Earth's path.

Researchers also hypothesize that the asteroid broke off from the huge asteroid Pallas, causing the spray of dust and debris. But NASA meteor expert Bill Cooke said the shower's dust particles don't match that hypothesis well.

Because of Phaethon's daring dives past the sun, researchers have suggested that the heat blasts the particles we see off of the asteroid. Phaethon reaches more than 1,300 degrees Fahrenheit (700 degrees Celsius) and seems to get a dusty tail during that passage near the sun.

Early birds' friend

While most meteor showers are best seen after midnight, the Geminids have a special appeal to early birds. These meteors appear in the sky as early as 10 p.m. local time, Cooke said, although they peak at 2 a.m. To see the Geminids, go to a dark area outside and prepare to settle in for the long haul — allow at least 30 minutes for your eyes to adjust, lean back and look at the whole sky, because the meteors can appear anywhere. And if it's cold where you are, don't forget to bundle up!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.