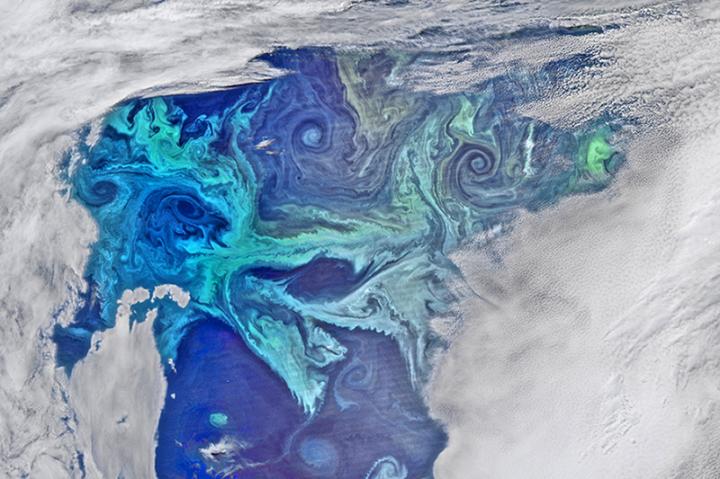

Discovery: Why Strange, Chalky Swirls Cover the Southern Ocean

Behold the Great Calcite Belt, ring around the Southern Ocean, coverer of 16 percent of all the global seas, and shiny bloom of microscopic phytoplankton so large it's best seen from space.

Organisms called coccolithophores — tiny, single-celled photosynthesizers that are neither plants nor bacteria — dominate those microscopic swarms, researchers recently discovered.

A team of scientists took two cruises, each one month long, through the great belt in the Southern Hemisphere summers of 2011 and 2012. The researchers went there to study the ocean chemistry that gives rise to an annual algal bloom, as well as the swarms of algae that make it up, reporting their results Nov. 7 in the journal Biogeosciences. [Gallery: Scientists at the Ends of the Earth]

Coccolithophores cover their bodies in plates of chalk (calcium carbonate) as they grow. When they concentrate together in the ocean, that chalk reflects light back into the sky, giving the water a milky-blue color. The result, when seen from above, looks as if Dr. Seuss ran into Vincent Van Gogh, leaving behind a quirky cast of blue-green iridescent swirls on the sea.

High levels of dissolved iron in the the belt, as well as favorable temperatures and carbon dioxide levels, create ideal conditions for the coccolithophores to grow their plated bodies.

Also favorable, the authors reported, were the low levels of silica in the area. Coccolithophores compete for resources with another form of phytoplankton, known as diatoms, which need silica to build their glassy exoskeletons. Low silica levels in the belt held down the diatom population, allowing coccolithophores to flourish.

The researchers also questioned the previously held, straightforward model of the belt's role in the global carbon cycle. Coccolithophores do pull carbon into the ocean when they build their shells, but they also release carbon dioxide in the process. This research into the presence of coccolithophores in the belt, the scientists explained, will help further refine models of the global carbon cycle.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.