Cygnus Spacecraft Departs the Space Station: Here's the Awesome Science It's Doing

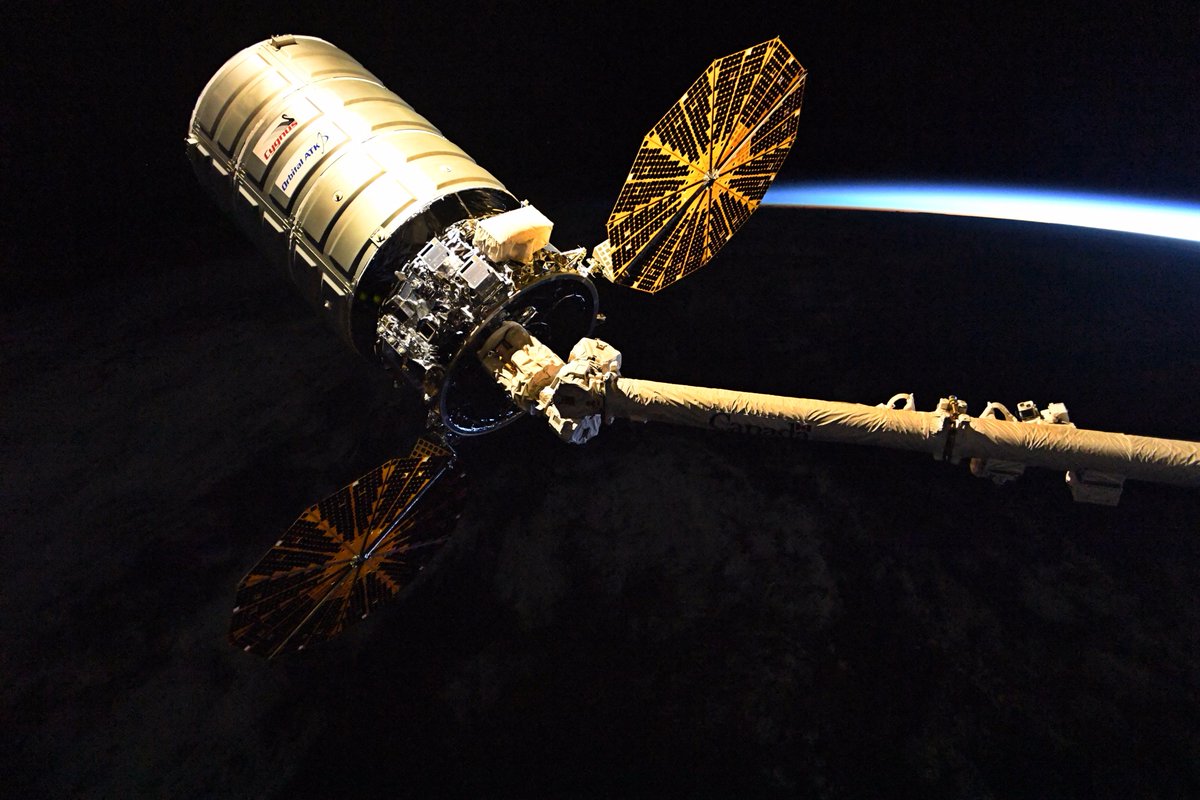

HOUSTON — Orbital ATK's Cygnus spacecraft departed the International Space Station (ISS) this morning (Dec. 6), on its way to do some bonus science before burning up in Earth's atmosphere after a successful cargo delivery mission.

Space.com learned about the spacecraft's possibilities as a science vessel (it will release 14 minisatellites after leaving the station) and potential future journey to deep space at a talk given by Frank DeMauro, vice president and general manager of Orbital ATK's Advanced Programs Division, here at SpaceCom 2017 yesterday (Dec. 5).

This Cygnus vehicle, called the S.S. Gene Cernan in honor of the late NASA astronaut who was the last person to walk on the moon, delivered more than 7,700 lbs. (3,500 kilograms) of cargo to the station in November, including about 1,900 lbs. (860 kg) of science experiments and tech demonstrations — plus some Thanksgiving dinner and other holiday goodies. Before Cygnus' departure today at 8:11 a.m. EST (1311 GMT), the space station crew filled it with trash that will burn up in Earth's atmosphere. [In Photos: Orbital ATK's OA-8 Cygnus Launch to Space Station]

The spacecraft detached from the station yesterday morning but stayed connected to the station's robotic arm until its release today. Next, the spacecraft will fly into a higher orbit than the space station and release small, experimental satellites called cubesats.

"This mission, we're actually flying 14 cubesats; that's by far more than we've done before," DeMauro said during the SpaceCom presentation. "We'll depart the ISS early in the morning, and then throughout the day, at three discrete times, we'll actually deploy three different bunches of the cubesats. That's important for the cubesat industry; we've done deployments below the ISS," but by releasing them higher up, "you can give those cubesats a lot more life."

Cygnus has run other experiments after leaving the space station in the past, DeMauro added; for instance, Orbital ATK has administered spacecraft fire safety experiments to test how things burn in space far from any vulnerable crew. On this mission, the space station crew also got to make use of the extra space Cygnus provided by setting up and running an experiment while it was berthed.

The spacecraft won't stay in orbit for long after releasing the cubesats, but DeMauro said the company is considering how to let Cygnus linger and do science long after its official mission is complete.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"One thing we're looking at is adding more capability to Cygnus, like a free-fire capability," DeMauro said. "We'll fly away from the ISS. We'll actually fly around for quite some time — up to a year or so on orbit, as opposed to just a couple of weeks after we leave the ISS.

"That affords customers the opportunity to get time and space on a mission where the primary mission has been completed, probably offering reduced cost to those customers so they can fly their sensors or other experiments on orbit and be able to get valuable data for a long period of time," he added. Companies could even use Cygnus to take an experiment away from the space station, run it and bring it back to the station for the crew to analyze, he said. And spots on the outside of the spacecraft could provide space to install additional sensors and experiments.

Up and away

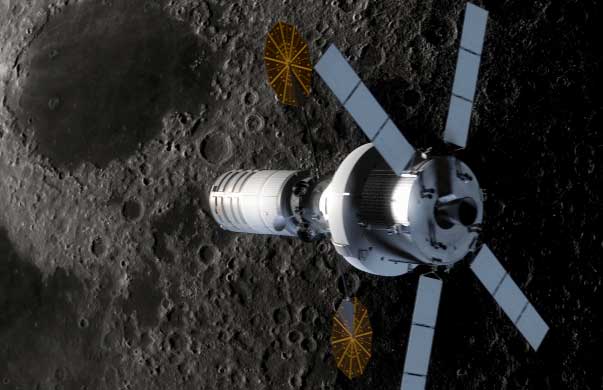

As part of NASA's NextSTEP-2 program, Orbital ATK is also developing a spacecraft based on Cygnus that would journey much farther — even up into orbit near the moon.

"Cygnus as designed is designed for low Earth orbit operations, including cargo," DeMauro told Space.com. "But a lot of the fundamental building blocks come from our geosynchronous satellite product line, which typically is high-radiation and can actually have a lot longer life.

"We're looking at how to take a derivative of the Cygnus vehicle and be able to use it out in cislunar space, either as a habitat for the Orion crew once they're out there, as a logistics module to bring supplies back and forth [or] a scientific test bed to house scientific experiments," he added.

To get Cygnus fit for more distant flight, engineers would have to add more radiation shielding, as well as shielding for the spacecraft's avionics systems to help them last longer, DeMauro said. Plus, that crucial machinery would probably have to move; right now, it's in a spot where it'd be impossible for the crew to reach to swap out a failed unit, he said.

"We think that Cygnus, as it's built right now, with some modifications that we're working on now through the NextSTEP program, can be an actual affordable cislunar habitat … and that we can get up there a little bit faster than waiting for the whole program with [NASA's] Deep Space Gateway," DeMauro said.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.