Surprise! New Horizons Probe's Next Flyby Target Has at Least One Moon

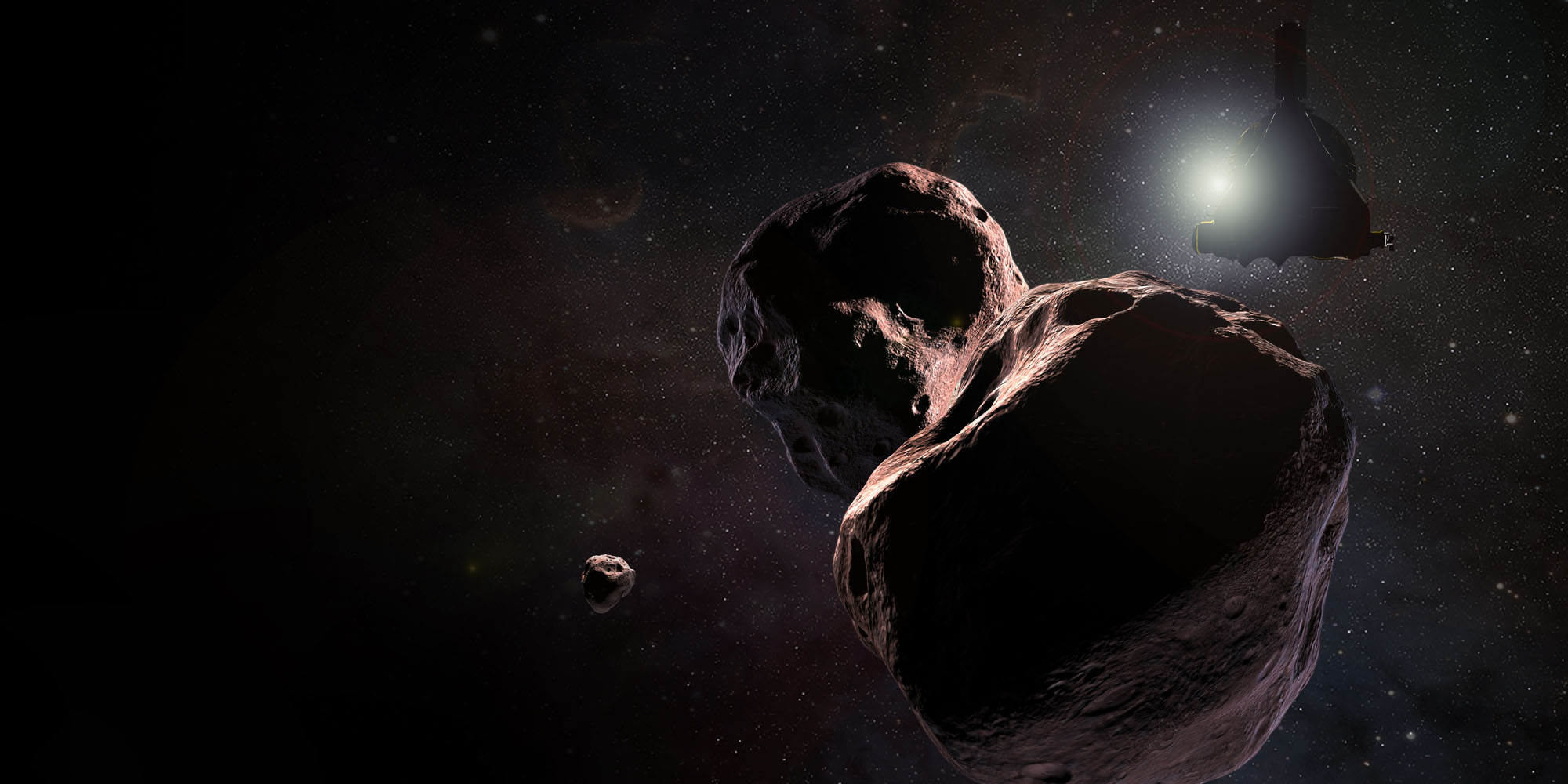

NEW ORLEANS — When NASA's New Horizons spacecraft arrives at its next destination in 2019, it may find more primordial objects than NASA had anticipated: Researchers have announced that the probe's next target, an icy object known as 2014 MU69, may have at least one moon and could even host a swarm of natural satellites.

"It is very exciting," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Colorado, told Space.com. Stern and his colleagues chased 2014 MU69 on land and through the air last summer as it occulted, or passed in front of, three background stars. The results suggest that the distant object has at least one moon, said the scientists who presented the results here yesterday (Dec. 12) at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting.

"This might be the harbinger," Stern said during a news conference at the AGU meeting. "It might hint that there is actually a swarm of satellites from MU69." [Wow! See New Horizons' Next Flyby Target Blot Out a Star's Light]

"MU" moon

After New Horizons slipped by Pluto in July 2015, it continued on through the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy objects beyond Neptune. The team quickly obtained permission to embark on an extended mission, with MU69 as its selected target.

In preparation for the upcoming visit, the scientists arranged to observe three occultations. The first and third sets of observations were made from the ground, and the second set was taken aboard the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), the world's largest airborne observatory.

Despite their best planning, the scientists saw no sign of MU69 during the first occultation, on June 3. "We thought we were in the right place, but it turns out we weren't," said New Horizons co-investigator Marc Buie, also at SwRI. On June 10, while flying over the Pacific Ocean, "we saw a little blip," Buie said. The signal was tiny and didn't look like the scientists expected it to, so they weren't certain it was real until they spent time analyzing it. (It was, indeed, real.)

"Then, on July 17, we hit the jackpot," Buie said. Five observatories spread across Argentina provided a wealth of data that revealed the object's unusual bilobed shape — but once again, the object wasn't sitting where previous observations suggested it should.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Together, the measurements suggest that MU69 isn't spinning through space alone, the researchers said. Rather, MU69's shifted location suggests that it is offset from its center of mass, hinting at the possibility of at least one natural satellite. In other words, the small blip Buie and his team spotted aboard SOFIA may be a tiny moon.

Stressing that the results were preliminary, Buie said the signal seemed to suggest a moon that's about 3 miles (5 kilometers) across, orbits about 124 to 186 miles (200 to 300 kilometers) from MU69 and circles the object every two to three weeks. Prior to the Jan. 1, 2019, flyby, New Horizons should be able to collect about three weeks' worth of data, watching the satellite go around at least once, Buie told Space.com.

Stern said that if this moon makes MU69 wobble, it might be possible to measure the mass of both, which would allow scientists to determine the density of MU69 and make some general conjectures about its composition. From there, they could estimate the ratio of ice to rock in this primordial object.

"That's very, very exciting," Buie said.

And this moon might not be the only satellite orbiting MU69, the scientists said.

The odds that SOFIA happened to capture a glimpse of a solitary moon are slim, Stern said. It may be that MU69 has a system of multiple moons and that the flying observatory spotted one of many.

Moons are common in the Kuiper Belt, Buie said. In fact, some scientists suggest that every object might host at least one. Before and after its flyby of MU69, New Horizons will survey about 30 other objects and may spot moons around some of those, as well. According to Stern, the mission has enough power and fuel to operate until the mid-2030s, and perhaps even longer, should NASA decide to continue funding its exploration. And although most of New Horizons' targets will appear as points of light, it's possible that another new moon could be discovered.

"We'll be looking," said New Horizons deputy project scientist John Spencer, also of SwRI.

When MU69 is firmly in the rearview mirror, New Horizons will continue on through the Kuiper Belt and out of the solar system. Like NASA's Voyager 1 mission, New Horizons has enough speed to escape the solar system entirely.

"There's nothing that can slow us down," Stern said. [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

Christmas in the Kuiper Belt

While people on Earth are ringing in the new year in 2019, New Horizons will be making contact with MU69. The spacecraft will go into hibernation next week and won't wake up until August 2018, according to New Horizons mission operations manager Alice Bowman, of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. As it closes in on MU69, the probe will hunt for other moonlets and previously unseen rings. If its course requires adjustment to avoid danger, the craft will have nine opportunities between October and the end of December 2018 to make a move.

"We are entering the unknown here," Spencer said. "We don't know what the system is like. We're prepared for the unexpected."

On Dec. 25, 2018, the last commands will be sent, and the spacecraft will switch into encounter mode, "spend[ing] Christmas in the Kuiper Belt," Stern joked. On Jan. 1, 2019, at 12:33 a.m. EST (0533 GMT), New Horizons will make its closest approach to 2014 MU69, passing within 2,175 miles (3,500 km) of the object's surface and capturing images that should be even more detailed than those it took of Pluto.

"We certainly expect to see craters," Bowman said. MU69 also could have strange grooves like those that scar the surface of the Martian moon Phobos, she said. The mission team will hunt for a variety of ices and try to solve the mystery of what makes the object take on its reddish hue, Bowman said.

By 10 a.m. EST (1500 GMT) on Jan. 1, 2019, the team should know if New Horizons made it through the MU69 system safely, Bowman said, and images will begin streaming down over the following week before the spacecraft travels behind the sun. While out of contact for several days, New Horizons will take a long series of unbroken images and then begin transmitting the data home, she said.

And that data transfer will take a long time. From MU69 — which lies nearly a billion miles beyond Pluto— a one-way signal from New Horizons will take more than 12 hours to get to Earth. Plus, the probe can send only a little at a time — it took 16 months to get back all the data from its Pluto flyby. According to Stern, getting all of the data back on the ground from New Horizons' visit to MU69 will take all of 2019 and most of 2020.

"The news will just keep raining down from the Kuiper Belt," Stern said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd