Bruce McCandless, Astronaut Who Made First Tetherless Spacewalk, Dies at 80

The first astronaut to become his own spacecraft, strapping on a jet-powered backpack and flying tether free during a historic spacewalk, has died.

Bruce McCandless II, who also served as Neil Armstrong's contact in Mission Control when the Apollo 11 moonwalker took "one small step" onto the lunar surface in 1969, died on Thursday (Dec. 21), NASA confirmed. He was 80.

"Our thoughts and prayers go out to Bruce's family," said NASA Acting Administrator Robert Lightfoot in a statement on Friday (Dec. 22).

The youngest member (at 28) of the fifth group of NASA astronauts selected in 1966, McCandless waited 18 years to make his first of two flights aboard the space shuttle. He logged 13 days and 31 minutes off the planet, including 12 hours and 12 minutes conducting two spacewalks.

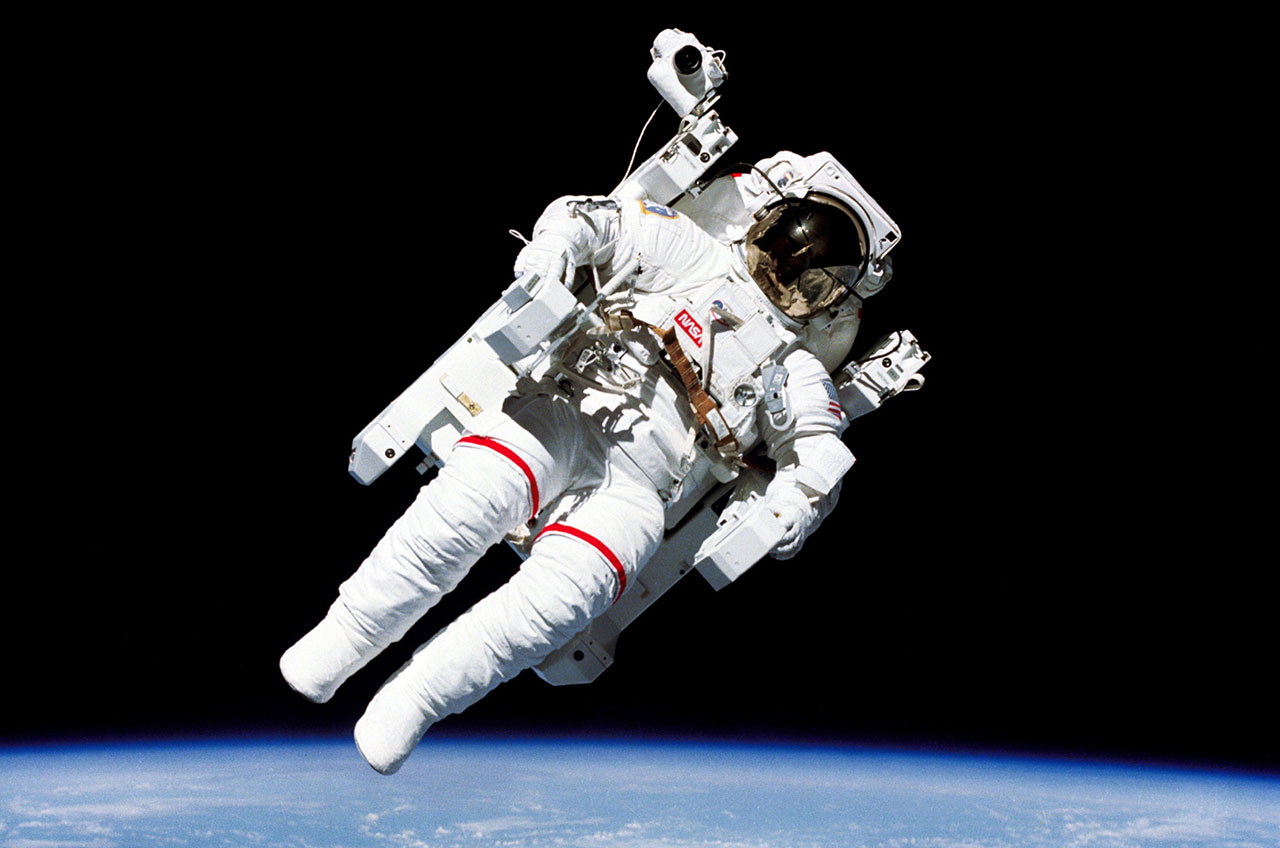

It was on his first extravehicular activity that McCandless donned a Manned Maneuvering Unit, or MMU, and made history by jetting away from the space shuttle Challenger.

"That may have been one small step for Neil but it's a heck of a big leap for me!" exclaimed McCandless, floating free for the first time on Feb. 7, 1984, and invoking Armstrong's first words on the moon 15 years earlier.

McCandless, who helped develop the MMU prior to testing it in orbit, used its gas thrusters to back away to a distance of 320 feet (98 meters) from Challenger.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Once you are accustomed to seeing the Earth rushing by at 4 miles per second [6 km/s], and you concentrate on the orbiter ... as your reference at hand, you feel comfortable flying around at the relatively slow velocities," McCandless said after the mission was over. "It is sort of like two rather fast airplanes flying formation around one another."

McCandless and his fellow STS-41B crew member Robert Stewart put the MMU through its paces, inside and outside of Challenger's payload bay. During a second spacewalk, President Ronald Reagan called the shuttle to speak to the two astronauts.

"Let me ask you," began Reagan, addressing McCandless and Stewart, "what's it like to work out there, unattached to the shuttle, maneuvering freely in space?"

"It feels quite comfortable. The view is simply spectacular and panoramic," replied McCandless while strapped in the MMU in the cargo bay. "We believe that maneuvering units first time working unattached, we're literally opening a new frontier for what man can do in space."

NASA ultimately retired the MMUafter six astronauts used it on three shuttle missions, but crew members using U.S. spacesuits at the International Space Station don a smaller jetpack for emergency use if they become separated from the orbiting laboratory.

McCandless launched on board his second spaceflight on April 24, 1990, on a mission to deploy the Hubble Space Telescope. The STS-31 crew released the observatory into Earth orbit, but not before McCandless was almost called upon to do a third spacewalk.

One of the two solar arrays that powered the Hubble hit a snag while being unfurled. McCandless and Kathy Sullivan were preparing to go out on a contingency spacewalk, pre-breathing pure oxygen inside Discovery's airlock, when the array freed itself, negating the need for the outing.

Years later, after the Hubble Telescope's flawed optics had been corrected and a fifth and final servicing mission was briefly canceled by NASA, McCandless became a leading advocate for a robotic servicing mission to extend the life of the astronomical instrument on orbit.

"I'm a proponent for extending the Hubble Telescope's use to until the James Webb Space Telescope is launched and confirmed as operating," McCandless told collectSPACE.com in 2005. "I support either a manned or robotic approach."

The Hubble Space Telescope was upgraded once again in 2009 and remains in operation. The JWST is scheduled for launch in 2019.

Over the course of his two flights, McCandless traveled 5.4 million miles (8.7 km), completing 208 orbits around Earth. He retired from the NASA astronaut corps in August 1990, four months after returning from space aboard Discovery, and later went to work for Lockheed Martin in Colorado.

Bruce McCandless II was born on June 8, 1937, in Boston, Massachusetts. He earned his bachelor of science degree from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1958 (graduating second in his class) and his masters of science degree in electrical engineering from Stanford University in 1965.

Later, after becoming an astronaut, he earned a master's in business administration at the University of Houston, Clear Lake, in 1987.

McCandless became a naval aviator in 1960. He saw duty on the aircraft carriers Forrestal and Enterprise, including the latter's role in the 1962 Cuban blockade. He served as an instrument flight instructor in Attack Squadron 43 at the Naval Air Station in Oceana, Virginia, and then reported to the Naval Reserve Officers' training corps unit at Stanford University for graduate studies in electrical engineering.

A captain in the U.S. Navy, McCandless logged more than 5,200 hours flying time, 5,000 in jet aircraft.

Before launching into space and in addition to his role as a Capcom during the Apollo 11 mission (his call, "Neil, this is Houston. We're copying," were the first ever words spoken to a human standing on the moon), McCandless served as a support crew member for the Apollo 14 lunar landing in 1971 and as the backup pilot for the first crewed mission to the Skylab orbital workshop in 1973.

Though he once filed suit against the pop singer Dido for the unauthorized use of his MMU spacewalk photo on her album cover, McCandless said he appreciated the fact that his identity was hidden from view in the iconic image.

"I have the sun visor down [on my spacesuit's helmet], so you can't see my face, and that means it could be anybody in there," he said in an interview with Smithsonian magazine in August 2005. "It's sort of a representation, not of Bruce McCandless, but mankind."

He is a recipient of numerous honors, including the NASA Exceptional Service Medal, the NASA Space Flight Medal, the National Aeronautic Association Collier Trophy and the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum Trophy. He was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in New Mexico in 1995 and the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in Florida in 2005.

McCandless held a patent for a tool tethering system that was used during space shuttle spacewalks.

McCandless is survived by his wife, Ellen Shields, and two children, Bruce and Tracy, who he had with his first wife of 53 years, Bernice Doyle, who died in 2014. McCandless is also survived by two granddaughters, by a brother and two sisters.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2017 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, an online publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018. He previously developed online content for the National Space Society and Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, helped establish the space tourism company Space Adventures and currently serves on the History Committee of the American Astronautical Society, the advisory committee for The Mars Generation and leadership board of For All Moonkind. In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History.