Does It Snow In Space?

This week's winter storm leaves no doubt that snow feels right at home on planet Earth. But what are winter conditions like elsewhere in the universe? Will humans ever build a snowman on Saturn's moon Titan? Will someone have to shovel the Curiosity rover out of its parking spot on Mars?

The idea of interplanetary snow sounds reasonable: All you need is ice and something in the atmosphere for that ice to cling to, right? Alien meteorology is a tad more complicated than that, but emerging space science confirms that, yes, space snow is indeed a thing. [Mars Rover Curiosity's 7 Biggest Discoveries (So Far)]

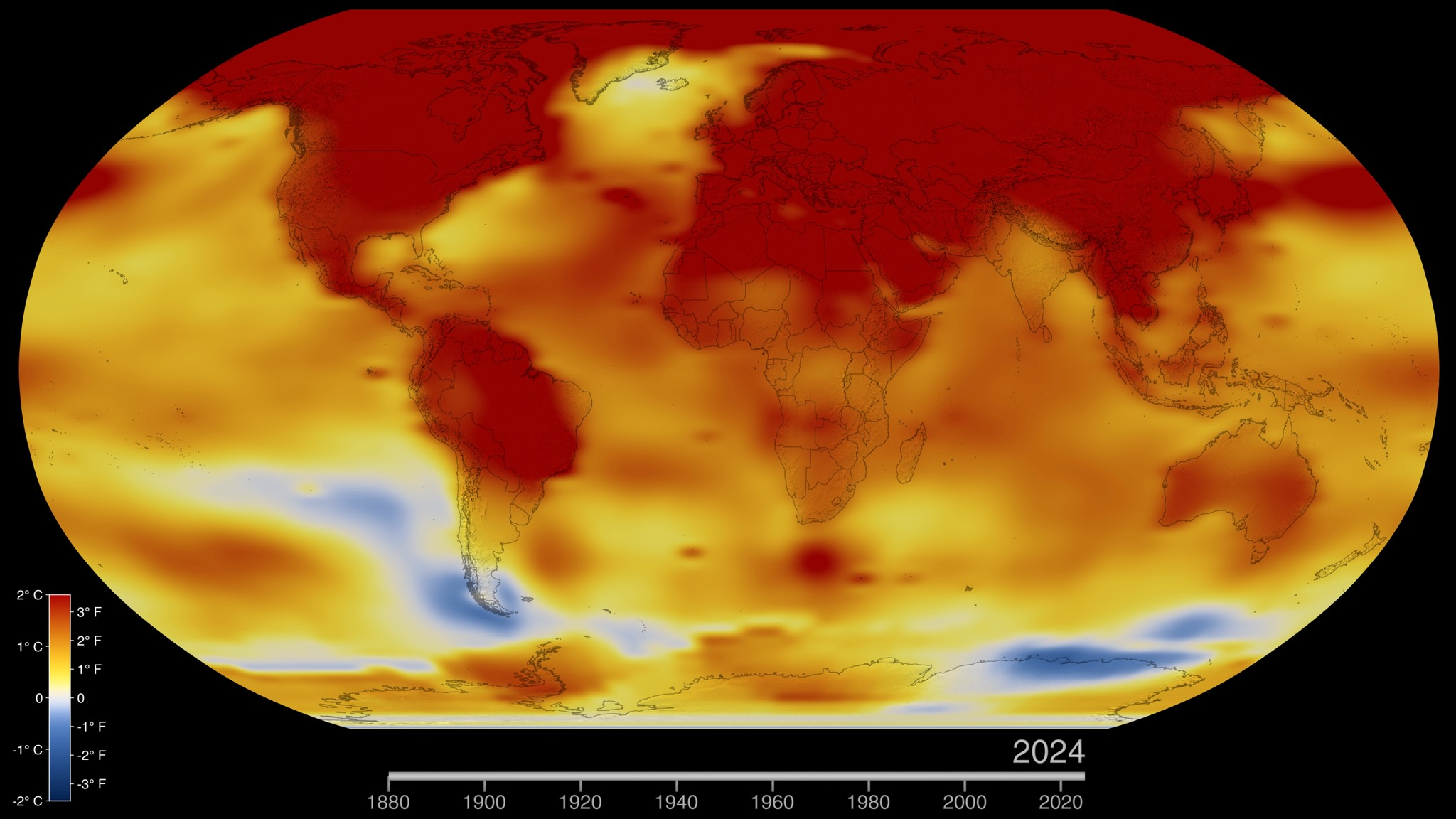

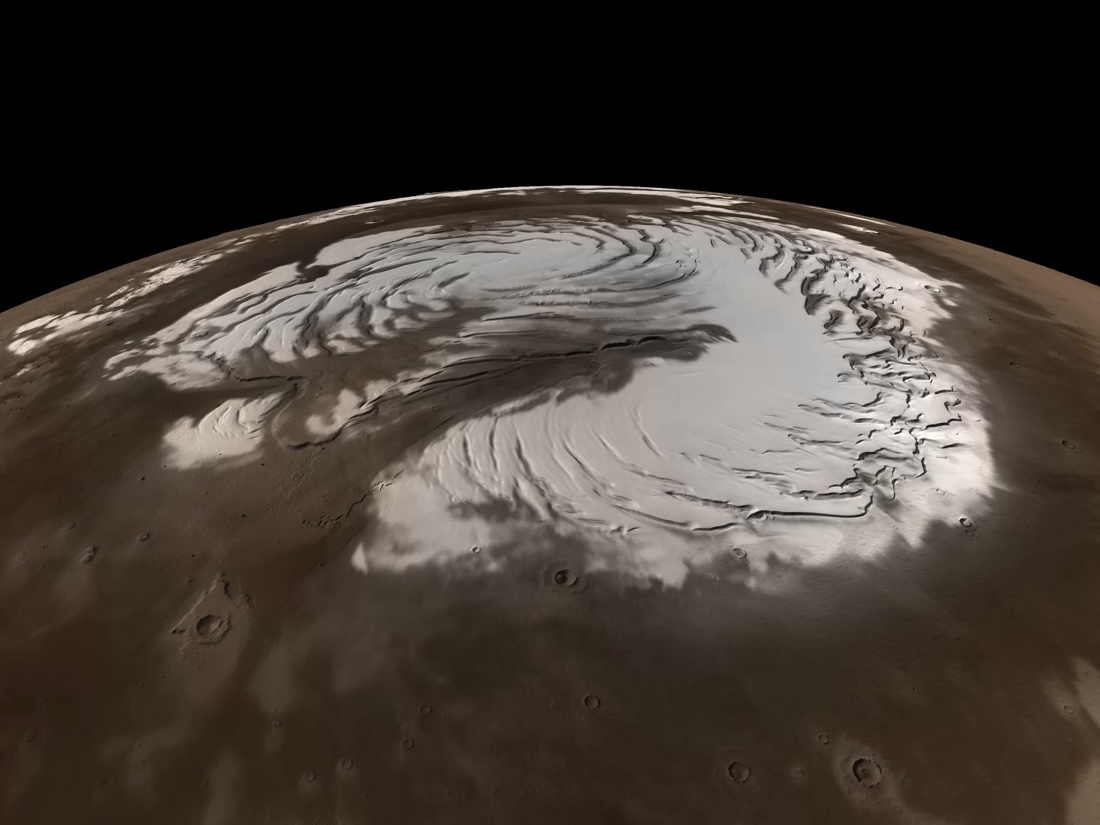

The best-studied examples occur right next door on the Red Planet. Scientists have already observed snowfall several times on Mars. With an average temperature of about minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 60 degrees Celsius), the nearby planet is certainly cold enough for snow. In 2008, NASA's Phoenix lander caught water-ice snow — the fluffy stuff we're used to on Earth — falling near the planet's north pole.

Meanwhile, the Martian south pole wears a cap of frozen carbon dioxide (aka, "dry ice") year round. In 2012, researchers spotted a dry-ice snow falling from Mars' atmosphere around the south pole for the first time.

Despite a steady supply of clouds, snow rarely accumulates on the Red Planet's surface. Because Mars' atmosphere is so thin — about 100 times thinner than Earth's — liquid water falls very slowly and tends to vaporize almost immediately. Scientists have observed clouds dropping snow high in the Martian atmosphere, only to see the precipitation vanish before getting anywhere near the surface (this happens on Earth too, in a phenomenon called virga).

Surface snow may be possible on Mars under the right conditions, though, according to a study from late 2017 in the journal Nature Geoscience. Because Martian temperatures can plummet nearly 200 degrees F (111 degrees C) between day and night, turbulence within clouds is common.

"This can lead to strong winds, vertical plumes going upward and downward within and below the clouds at about 10 meters [33 feet] per second," Aymeric Spiga, a planetary scientist at the University of Pierre and Marie Curie in Paris, previously told Space.com. Under storm conditions like these, snow could drop to Mars' surface quickly enough to stick overnight — but it would still vaporize come morning.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

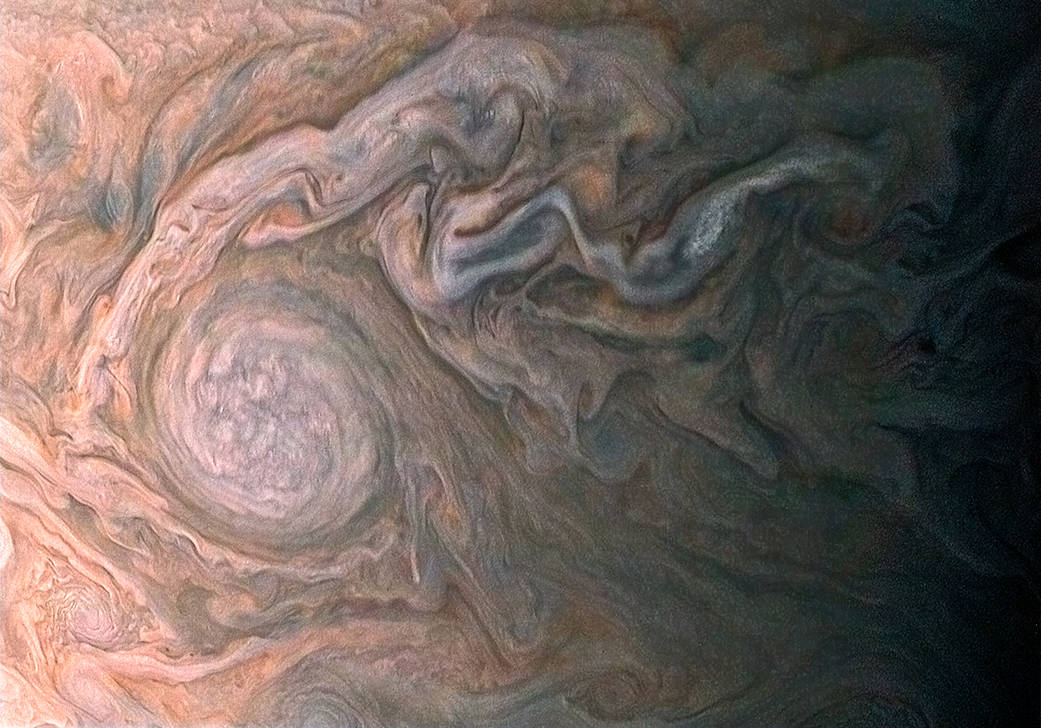

What about elsewhere in our solar system? Clouds seen swirling high above Jupiter's surface in May 2017 would almost certainly be frozen, scientists said, and likely to drop an icy mix of water and ammonia that could be considered something between snow and hail.

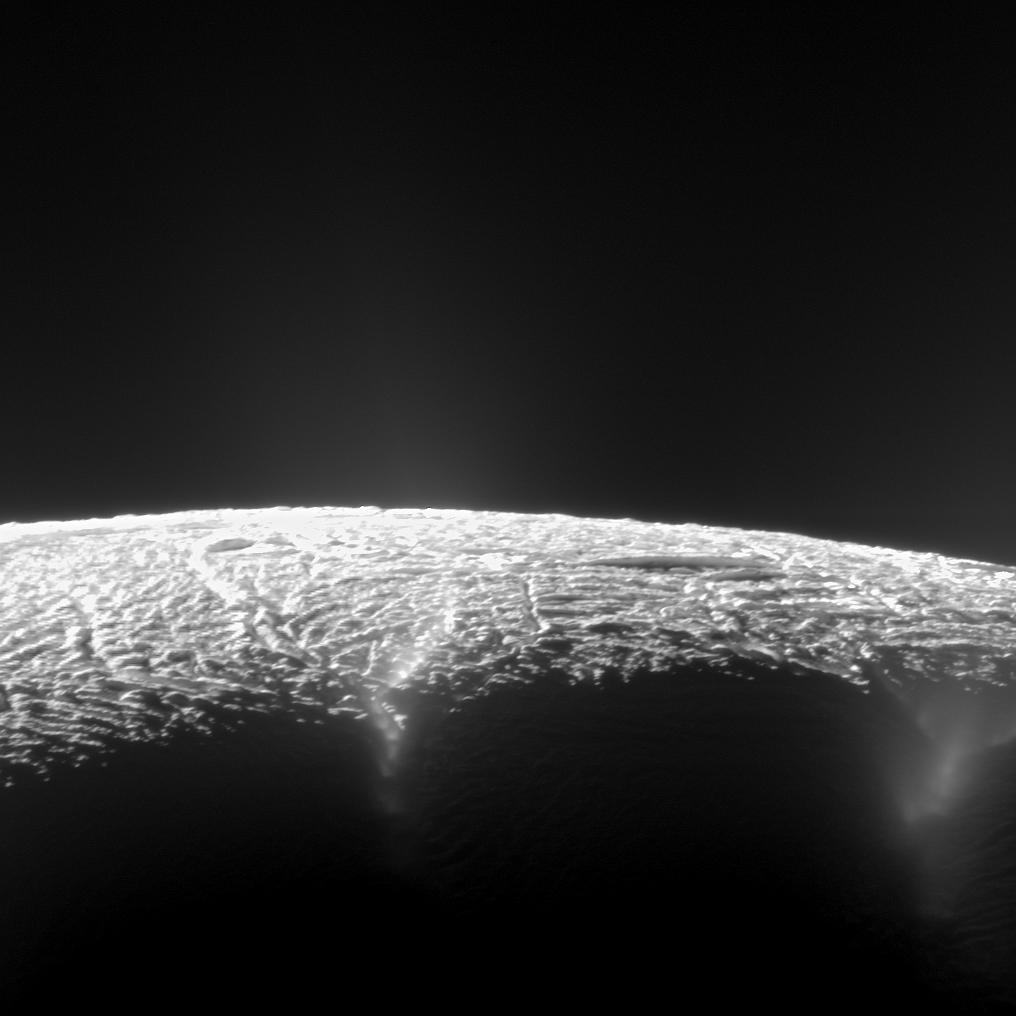

Meanwhile, Saturn's sixth-largest moon, Enceladus, might be the best spot for interplanetary skiing, according to data taken from NASA's late-great Cassini probe in 2011. The spacecraft found that ice particles ejected by geysers on the icy moon fall back onto Enceladus' surface in a predictable pattern, creating slopes of superfine crystals that would likely be perfect for slaloming. Don't count on a season pass, though: The crystal "snow" falls at an extremely slow pace by Earth standards: less than a thousandth of a millimeter per year, the scientists said.To accumulate roughly 320 feet (100 m) would require a few tens of millions of years.

Elsewhere, it gets weirder. On Kepler-13Ab, a massive exoplanet planet that's six times larger than Jupiter and that lies 1,730 light-years from Earth, it snows titanium dioxide, one of the active ingredients in sunscreen. Oh, also, it might rain diamonds on Uranus and Neptune.

The fluffy, frozen water we get here on Earth might seem boring in comparison, but at least you can sit back, relax and capture stunning photos of it from the cozy comfort of your home. Remember: In space, nobody can hear you Instagram.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.