Going into Space Crushes the Delicate Nerves in Your Eyeballs

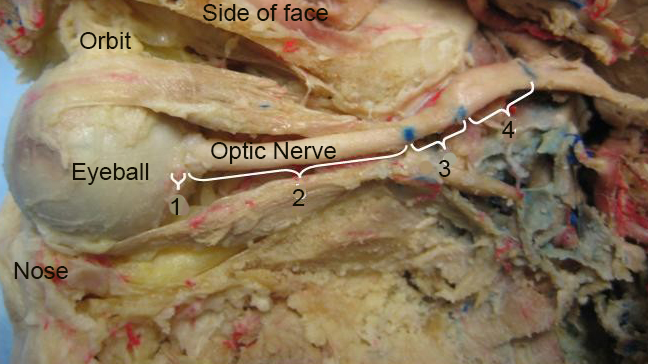

Two delicate, bundled stalks of nerve tissue erupt forward from the brain, slip between gaps in the backs of each eyeball, and attach themselves gently to the rear of each retina. These are the optic nerves, the transmitters linking human beings to their powers of sight. And now researchers have shown that space travel puts a powerful, dangerous squeeze on their fragile tips.

A study of 15 astronauts who had been on missions in orbital freefall for about six months found that the tissues at the backs of their eyes — tissues that surround the heads of their optic nerves — tended to look warped and swollen in the weeks after their return to Earth. This change could help explain why nearly half of long-term space travelers develop significant vision problems, according to the study, published today (Jan. 11) in the journal JAMA Ophthalmology.

This isn't the first study to demonstrate that space travel changes the shape of the eye; a 2011 paper published in the journal Ophthalmology showed that there were changes to the internal anatomies of astronauts' eyes. But the new study is the first to show direct, damaging changes to the optic nerve. [Photos: The First Space Tourists]

That's a big deal, because as NASA slowly (ever so slowly) works toward long-term crewed missions into deep space, it needs to understand how those missions are likely to impact astronauts' health.

Many of the 15 astronauts in the study had pre-existing eye damage (likely from previous missions) before the trips to space documented in this study. But images of their Bruch membrane openings — the gaps in the back of the eye through which the optic nerve travels — showed those tissues moving deeper into the eye after long-term missions and swelling significantly after the astronauts returned to Earth.

It's not clear exactly why this happens, but the researchers offered a guess: Perhaps the internal pressure in the eye increases while the astronauts are up in space, and over time, the surrounding tissues get used to that new pressure. Then, upon return to Earth's gravity, that pressure might quickly drain away. The rapid change could irritate and deform the eye's internal tissues.

The researchers don't offer a solution to this problem, and it's not clear that it's a problem within NASA's capacity to solve. But it's an issue the human spaceflight program will have to think about carefully as it asks its workforce to endure longer and longer stints in outer space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.