Manuel Laureano Rodríguez Sánchez (1917-1947), better known as Manolete, is considered by some to be the greatest bullfighter of all time. Of course, Manolete faced down his bovine opponents in a bullfighting ring with a large crowd looking on. It is a bit of a different scenario in our current night sky, where we can see another form of bullfight, this one between a charging bull and a mighty hunter.

Our "Manolete of the sky" is none other than Orion, the most prominent constellation. And he is certainly doing battle with a "bullish" competitor: Taurus, the Bull.

In a modern bullfight, the matador uses a special lance (a pica) and banderillas (little flags), as well as his emblematic cape. But Orion is equipped with a club, a sword and a lion's skin for a shield. [Constellations of the Night Sky: Famous Star Patterns Explained (Images)]

The most powerful

Taurus appears to be descended from a mythical heavenly Sumerian bull, an animal that used its great horns to open up the year and usher in spring, to plough the long furrow of the sky that was the zodiac.

This association with springtime came about because the stars of Taurus became prominent in the sky around the vernal (spring) equinox from about 4500 B.C. to 2000 B.C. During this time, the equinox was the most important date in the year. For the Sumerians, it was a time of rejoicing, their equivalent of New Year's Day, when the dark and cold winter season was ending and there was a feeling of new life in the air. Thus, for a long time, Taurus was the first and most powerful of the zodiacal constellations.

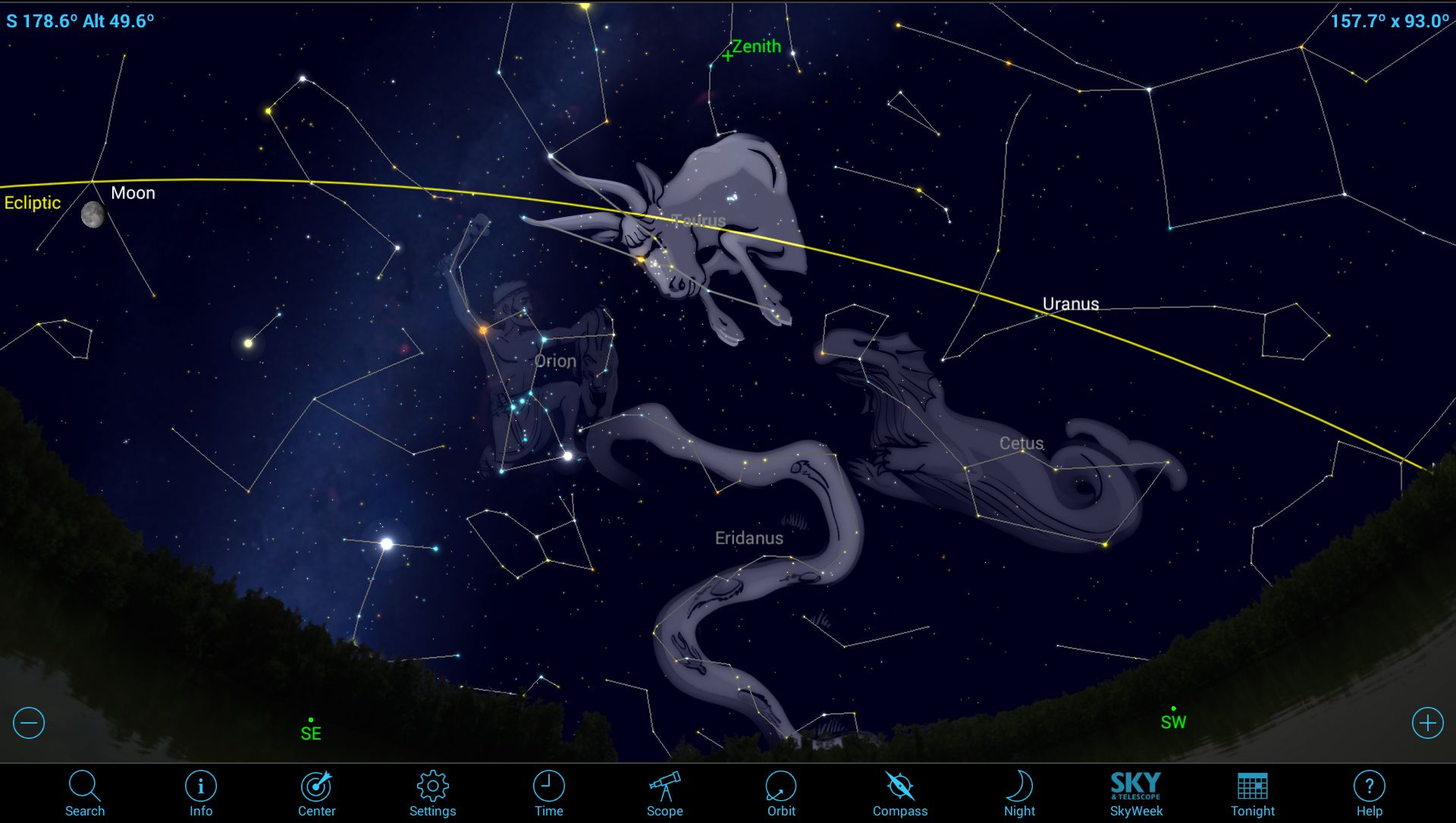

This week, the constellation Taurus is positioned at its highest point in the south and nearly overhead at around 9 p.m. local time. When I give shows under the sky of the "pretend universe" of a planetarium or conduct star-identification sessions under the real sky, I always identify Taurus as an angry bull.

But why is he so angry?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Hardly second-rate

Last month, I wrote a column about how, at this time of year, stargazers seem to concentrate solely on Orion, while all the other constellations surrounding him are seemingly nothing more than celestial second-stringers or part of a supporting cast.

I used the analogy of a house spangled with Christmas lights while nearby homes are more modestly decorated.

Perhaps Taurus is angry because he feels he shouldn't be considered a mere second banana to Orion (and consequently wants to take his frustration out on the hunter). Indeed, that anger at second billing is justified; our Heavenly Bull contains a wealth of interesting objects to see, and among all the star patterns, should certainly be categorized as first-rate.

The Seven Sisters

Probably the most noteworthy feature of Taurus is a small, concentrated group of stars called the Pleiades, or Seven Sisters. Few star figures are as familiar as the Pleiades. If you have difficulty in recognizing various stars and constellations, you should start with the Pleiades, because there is really nothing else like them in the sky, and nobody can look at the sky on a frosty winter night very long without noticing these sisters and wondering what they are.

To the average eye, this group looks at first like a little, luminous cloud. But further examination, aided by good eyesight, will reveal a tight cluster of six or seven stars, though some observers have recorded a dozen or more stars under excellent conditions. I know one gentleman blessed with such acute vision that he has claimed to see as many as 19 Pleiades stars from under exceptionally dark skies in Arizona.

The Pleiades grouping might be one of the first astronomical subjects recorded. It was known to the Greek poet Hesiod nearly 3,000 years ago, and a reference to it has been found in Chinese annals dated to around 2357 B.C. It is also mentioned three times in the Bible.

So apparent is the group that almost all cultures concerned with the sky have told tales of these stars' significance. For cultures of Central and South America, an important time of year began when the Pleiades appeared at their highest point at midnight. The ancient Greek astronomer Hipparchus dated the starts of seasons according to certain risings and settings of this group.

Several stars in the cluster seem to be enveloped in clouds of dust, perhaps left over from the stuff from which they formed. At 410 light-years away from us, and some 20 light-years across, the group may be no older than 20 million years. It contains a total of perhaps 250 stars.

And just subjectively, I believe the Pleiades are worth the cost of any good pair of binoculars. In fact, they just might be the most beautiful binocular object you can view in the sky. [The Best Binoculars for Earth and Sky]

The Hyades and Aldebaran

The Bull's face is plainly marked by yet another cluster of stars in the shape of a V, known as the Hyades. Notice the bright orange star at the end of the lower arm of the V, which represents the Bull's fiery eye. That's Aldebaran, "the follower"; it rises soon after the Pleiades and pursues them across the sky.

The Hyades are among the nearest of the star clusters, which explains why so many of the separate stars in that grouping are visible. At a distance of 130 light-years, the Hyades are moving in the general direction of the star Betelgeuse in Orion while receding from us at the rate of 100,000 mph (160,000 km/h).

Aldebaran, on the other hand, is just an innocent bystander — not part of the Hyades at all. Instead, it is moving toward the south, almost at a right angle to the cluster's motion, and twice as fast. Taurus's V-shaped head is, therefore, going to pieces. For another 25,000 years or more it will pass for a V, but after 50,000 years, it will be nothing more than a random jumble of stars. \

A cosmic smoking gun

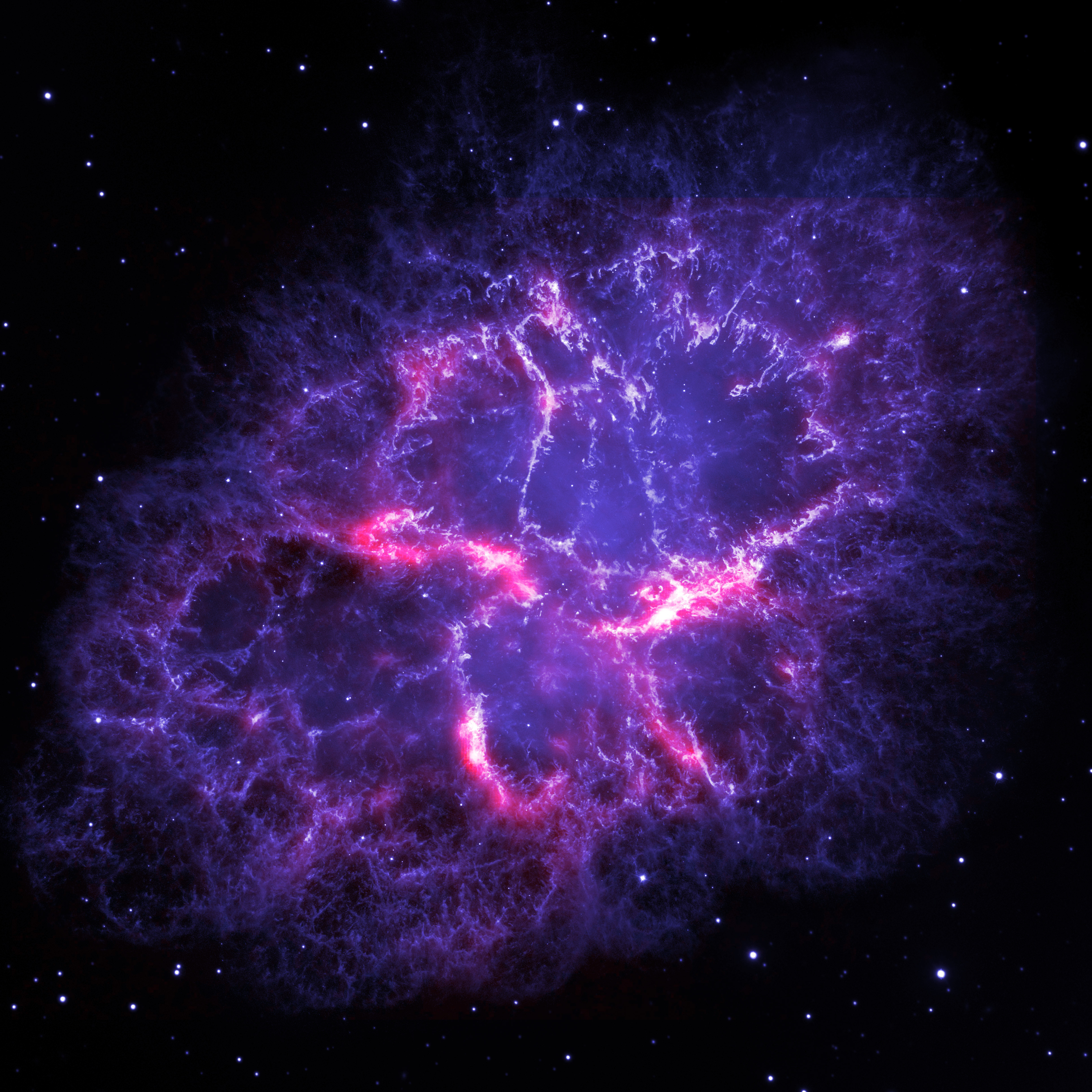

Back in the year A.D. 1054, an explosion of mammoth proportions took place: a supernova. A star at least 10 times more massive than our own sun suddenly blew apart; the bursting star likely blazed as brilliantly as our entire galaxy, the equivalent of 400 billion normal stars!

In the aftermath, nothing remained, except the intensely hot, newly revealed core of the star and an expanding cloud of gaseous debris. Fortunately, inhabitants of China, Japan and what is now the American Southwest were careful to note the position in the sky of this cosmic outburst: about two breadths of a full moon northwest of the star we know as Zeta Tauri, which marks the southern horn of Taurus.

The "guest star" that suddenly appeared there could easily be seen in daylight for more than three weeks. It finally faded completely from view after 653 days. The gas cloud that remained from the explosion is popularly known as the Crab Nebula and is still expanding outward in all directions at nearly 4 million mph (6.4 million km/h). [Photos: Amazing Views of the Famous Crab Nebula]

In November 1968, the core of the exploded star was discovered to be a pulsar, a rapidly rotating neutron star, which was spinning at an incredible rate of some 30 times per second! Apparently, there is a "hotspot" on the star's surface, which emits energy in virtually every part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Hence, as the star whirls on its axis, it appears to "pulse" from our earthly perspective.

This pulsar is extremely dense, packing about the mass of our sun into a volume measuring just 30 miles (50 kilometers) or so in diameter. Were it somehow possible to transport just a teaspoon of this material to Earth, it would weigh many hundreds of tons!

It was the Crab Nebula's resemblance to a telescopic comet that prompted astronomer Charles Messier to compile his celebrated catalogue of such fuzzy objects so that they might not deceive other comet hunters. The Crab Nebula is first on his list and is therefore known as M1.

Card-carrying member of the zodiac

Taurus is one of the 12 zodiacal constellations. This means that, periodically, the moon and one or more of the bright planets pass through this part of the sky, adding to the interest and luster of this beautiful, starry backdrop.

For instance, during the final days of April, the brilliant planet Venus will pass near the Pleiades, making an already-beautiful scene even more spectacular.

An "admirabull" sight, to say the least!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon Fios1 News, based in Rye Brook, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.