The Super Blue Blood Moon of 2018 May Unlock Secrets of the Lunar Surface

The upcoming Super Blue Blood Moon eclipse will not only be a treat for skywatchers; the rare celestial event will also give scientists a chance to discover some unknown characteristics about moon dust, like how porous and "fluffy" it is across the lunar surface.

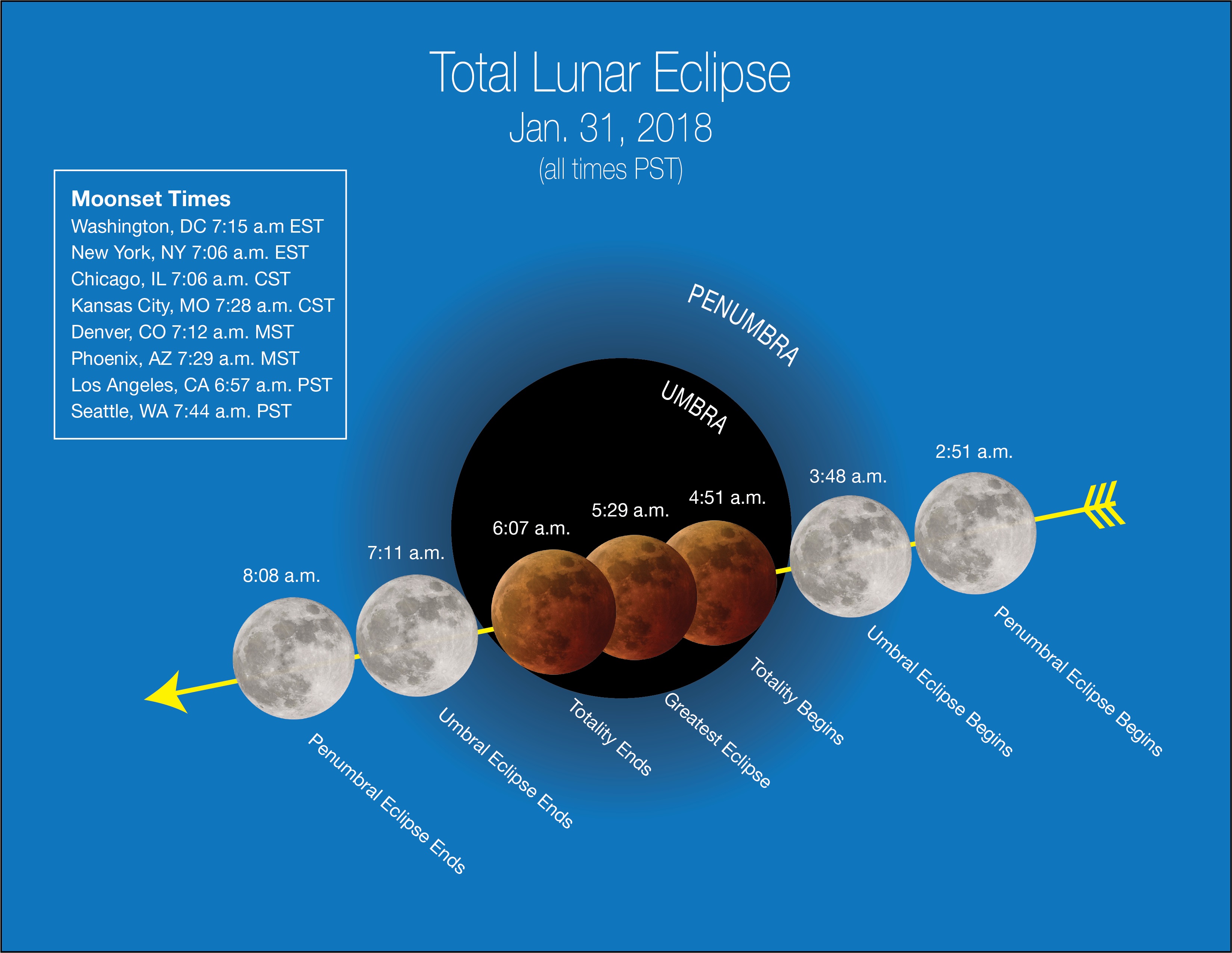

On Jan. 31, the full moon is in the perfect place to experience a triple effect: It will be close enough to Earth to be a supermoon, it will be a 'once in a blue' moon as a second full moon in a single month, and it will pass through Earth's shadow and appear red! If Super Blue Blood Moon sounds like a confusion of colors, here is some context: Expect a red or copper-colored full moon ("blood"). Here, "blue" does not refer to a shade. One explanation suggests it is a shortened form of "belewe," an old English word that meant "to betray," and can traced back to "Rede me and be not wrothe" from 1527.

Many folks across the United States witnessed the Great American Solar Eclipse of 2017, and during the fascinating moments before, during and after the moon blocked the sun's light, the ground got cold. On Jan. 31, the moon will experience a similar effect, as Earth blocks and bends sunlight that otherwise would fully illuminate and heat the moon, NASA officials said in a statement. The lunar surface will get chillier, and if NASA researchers notice that the moon's rocky surface cools down differently than it does in a normal moon day, the findings could clue scientists in on what those moon rocks are made of. [Super Blue Blood Moon 2018: When, Where and How to See It]

"During a lunar eclipse, the temperature swing is so dramatic that it's as if the surface of the Moon goes from being in an oven to being in a freezer in just a few hours," Noah Petro, deputy project scientist for NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the statement.

Petro and his team will run observations during the Super Blue Blood Moon at the Haleakala Observatory on the island of Maui in Hawaii, NASA officials said in the statement. They will be sensing heat changes over various places on the lunar surface, such as the dusty tadpole-shaped 37-mile-long (60 km) region known as Reiner Gamma.

A moon takes 29.5 Earth days to fully rotate and complete its own "day" — and, yes, it's the same amount of time as a month. That's because the moon is tidally locked with the Earth, meaning the same side always faces the blue planet. A moon day is how long it takes for all of the moon's surface to experience sunlight, just like an Earth day is how long it takes for all of the planet to get sunlight.

Lunar rocks regularly warm up and cool down as the surface moves between times of darkness and times of light. Scientists have studied this process before, and according to NASA, this information reveals a lot about the "bulk" of the regolith, or the dusty lunar rock soil. Sudden cooling changes from a lunar eclipse could reveal characteristics about the fine material at the top of the regolith, as well, NASA officials said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The whole character of the moon changes when we observe with a thermal camera during an eclipse," Paul Hayne, a researcher from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in the statement. "In the dark, many familiar craters and other features can't be seen, and the normally non-descript areas around some craters start to 'glow,' because the rocks there are still warm."

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.