Billions of Viruses Are Falling to Earth Right Now (But That Isn't Why You Have the Flu)

You can't see them or feel them, but millions of airborne viruses are wafting around you each day, and billions more microbial travelers are descending everywhere on Earth, after riding air currents around the world.

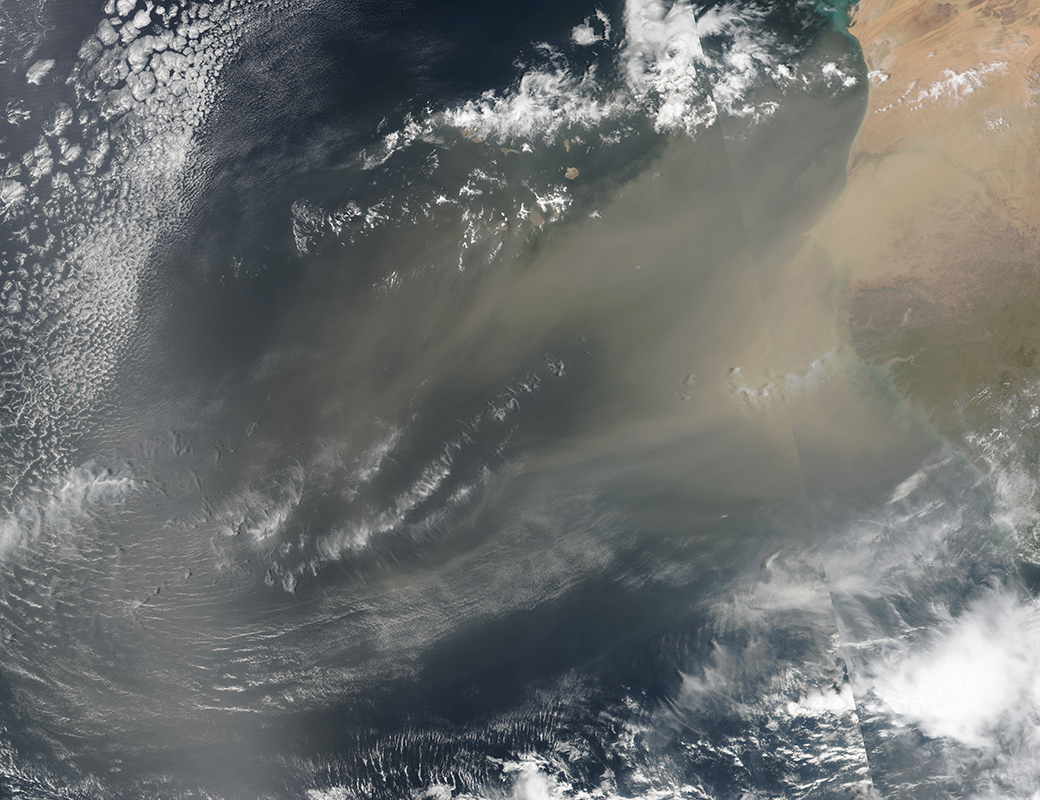

For the first time, scientists have analyzed the vast quantities of viruses that are swept up and swirling about in the atmosphere, sometimes traveling thousands of miles from their point of origin before seeing the planet's surface again. To do that, researchers looked at a boundary layer in the atmosphere — the free troposphere, which lies below the stratosphere but is still high enough to be beyond the reach of weather systems.

At this height, approximately 8,200 to 9,840 feet (2,500 to 3,000 meters) above sea level, viruses hitch rides on air currents and on particles of soil or vapor from sea spray, and travel much farther than would be possible at lower elevations. The scientists discovered a deluge of airborne microbes, finding that a single square meter of the planet's surface could be showered with hundreds of millions of viruses — and tens of millions of bacteria — in a single day. [Tiny Grandeur: Stunning Photos of the Very Small]

"Every day, more than 800 million viruses are deposited per square meter above the planetary boundary layer — that’s 25 viruses for each person in Canada," study co-author Curtis Suttle, a virologist and professor with the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia, said in a statement.

However, this virus "rain" has nothing to do with flu season. Viruses — clusters of genetic material in a protein envelope that can't reproduce on their own — have been around for at least 300 million years and are abundant on Earth (as well as in your body, as part of your microbiome).

In fact, viruses are the most abundant microbes on the planet, the study authors reported. The total estimated number of viruses is so staggeringly large that if all Earth's viruses were collected together they would cover an area spanning 100 million light-years, the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology reported in 2011.

Some viruses, such as influenza and Ebola, do sicken people, but manyinfectonly bacteria. Though it's unknown exactly how many types of viruses there are, approximately 320,000 types of viruses infect mammals alone, according to a study published in 2013 in the journal American Society for Microbiology.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scouring the skies

To track the invisible microbial highways in the sky — and find out how many viral passengers they carried — the authors of the new study ascended platforms in Spain's Sierra Nevada Mountains, and collected samples from the atmosphere at altitudes of about 9,840 feet (3,000 m) above sea level, scooping up free-floating microbes and those attached to airborne dust and water vapor.

When the scientists separated and analyzed the microbial hitchhikers, they found that not only were billions of microbes showering Earth's surface on a daily basis, but that viruses could be up to 461 times more abundant than bacteria. In the samples, viruses were attached to more of the organic, lighter particles than bacteria were, hinting that viruses could stay airborne longer and thereby travel greater distances, the study authors reported.

Their findings also answer a long-standing mystery as to why genetically similar virus populations could be found in areas that are separated by great distances, a discovery that dates to decades ago, Suttle said in the statement.

"Roughly 20 years ago we began finding genetically similar viruses occurring in very different environments around the globe. This preponderance of long-residence viruses travelling the atmosphere likely explains why," he said.

"It's quite conceivable to have a virus swept up into the atmosphere on one continent and deposited on another," he said.

The findings were published online Jan. 29 in the Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology.

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.