SpaceX Launched the World's Most Powerful Rocket. So, What's Next?

When SpaceX successfully launched its first Falcon Heavy booster Tuesday (Feb. 6) from the same Florida pad used by NASA's Apollo missions, the company claimed the title for the most powerful rocket. And for some companies, that might be a year-defining feat.

But SpaceX and its CEO, Elon Musk, have a lot more coming this year, including launching astronauts on its crewed Dragon spacecraft and preparing its Big Falcon Rocket (BFR) for potential tests in 2019.

First, there's the Falcon Heavy, on which SpaceX spent nearly $500 million over seven years to enter the heavy-lift market for launching huge satellites and spacecraft off planet Earth. The rocket can carry twice as much payload as its closest competitor (United Launch Alliance's Delta IV Heavy) at a lower cost, and its three first-stage boosters are designed to be reusable. For SpaceX, that's a launch vehicle triple threat.

"Falcon Heavy opens up a new class of payload," Musk told reporters after Tuesday's launch. "It can launch twice as much payload as any other rocket in the world … It can launch things right to Pluto and beyond, no stop needed." [SpaceX's 1st Falcon Heavy Rocket Test Flight in Pictures]

Falcon Heavy future

SpaceX's Falcon Heavy can launch up to 141,000 lbs. (64 metric tons) of payload into orbit, and sent Musk's Tesla Roadster on a deep-space ride toward the asteroid belt when the rocket blasted off from Pad 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, Tuesday. That lift capacity allows SpaceX to launch heavier satellites into low Earth orbit, or reach higher geostationary orbits used by some satellites to keep station over the same part of Earth.

SpaceX advertises Falcon Heavy flights for $90 million a launch. The Delta IV Heavy, meanwhile, can launch 32 tons (29 metric tons) into orbit and costs between $300 million and $500 million per flight, according to Tommy Sanford, executive director of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, told Space.com before the launch. That's a potentially huge cost savings.

Musk told reporters this week that, given a successful test flight, the next Falcon Heavy could launch within three to six months. And make no mistake: Tuesday's launch was a successful flight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Only two events didn't go as planned: The center core of the three-booster first stage missed its drone-ship landing and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, and a final engine burn of the rocket's second stage was stronger than expected, sending the Falcon Heavy's unique payload (Musk's Tesla Roadster and a mannequin named "Starman") into an orbit that extends out to the asteroid belt, beyond the orbit of Mars as initially planned.

There are two more Falcon Heavy missions expected to fly in 2018: the launch of a beefy communications satellite called Arabsat 6A; and Space Test Program 2 for the U.S. Air Force, a flight that will also launch the LightSail 2 solar sail for The Planetary Society.

SpaceX's flight manifest also includes future Falcon Heavy missions to launch satellites for the companies Inmarsat and Viasat.

So, Musk expects that SpaceX will be flying a lot of Falcon Heavy rockets — enough to ensure the boosters will be certified to launch heavy satellites on national security missions for the U.S. military. SpaceX launched its first Falcon 9 missions for the military in 2017.

"We have a number of commercial customers for Falcon Heavy," Musk said. "I really don't think it's going to be, in any way, an impediment to acceptance of national security missions."

Crewed Dragon flights

But remember, the Falcon Heavy isn't the end game for SpaceX and Musk in 2018. The company still plans to launch astronauts on its Falcon 9 and Dragon by the end of the year.

SpaceX has been flying uncrewed cargo delivery missions to the International Space Station for NASA for years, and in 2014, the space agency picked the Hawthorne, California-based firm as one of two companies to fly American astronauts to the station. (The other company is Boeing, which will launch astronauts on its Starliner crew capsule using Atlas V rockets.)

"We're making great progress on Crew Dragon," Musk said.

Mission assurance for each SpaceX launch is the company's No. 1 priority, with Falcon Heavy a close second until recently, Musk said. But a month ago, the Crew Dragon program took over that second spot.

"We're aspiring to fly crews to orbit at the end of this year," Musk said. "I think the hardware will be ready."

In fact, the spacesuit worn by SpaceX's Starman on the Falcon Heavy flight is the same one astronauts will wear on Dragon, he said.

SpaceX's BFR megarocket

And finally, there's the BFR: the ship Musk wants to use to colonize Mars.

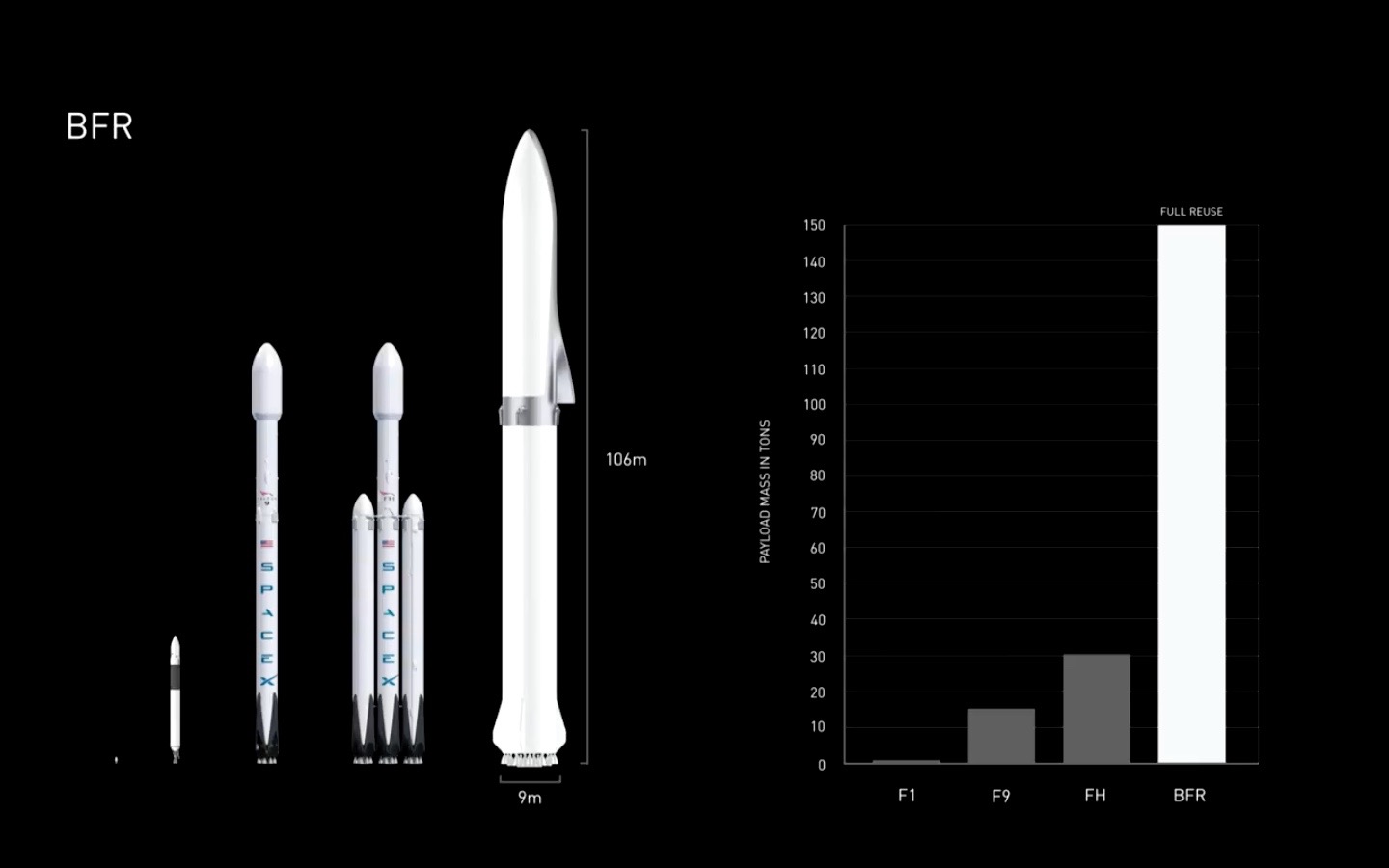

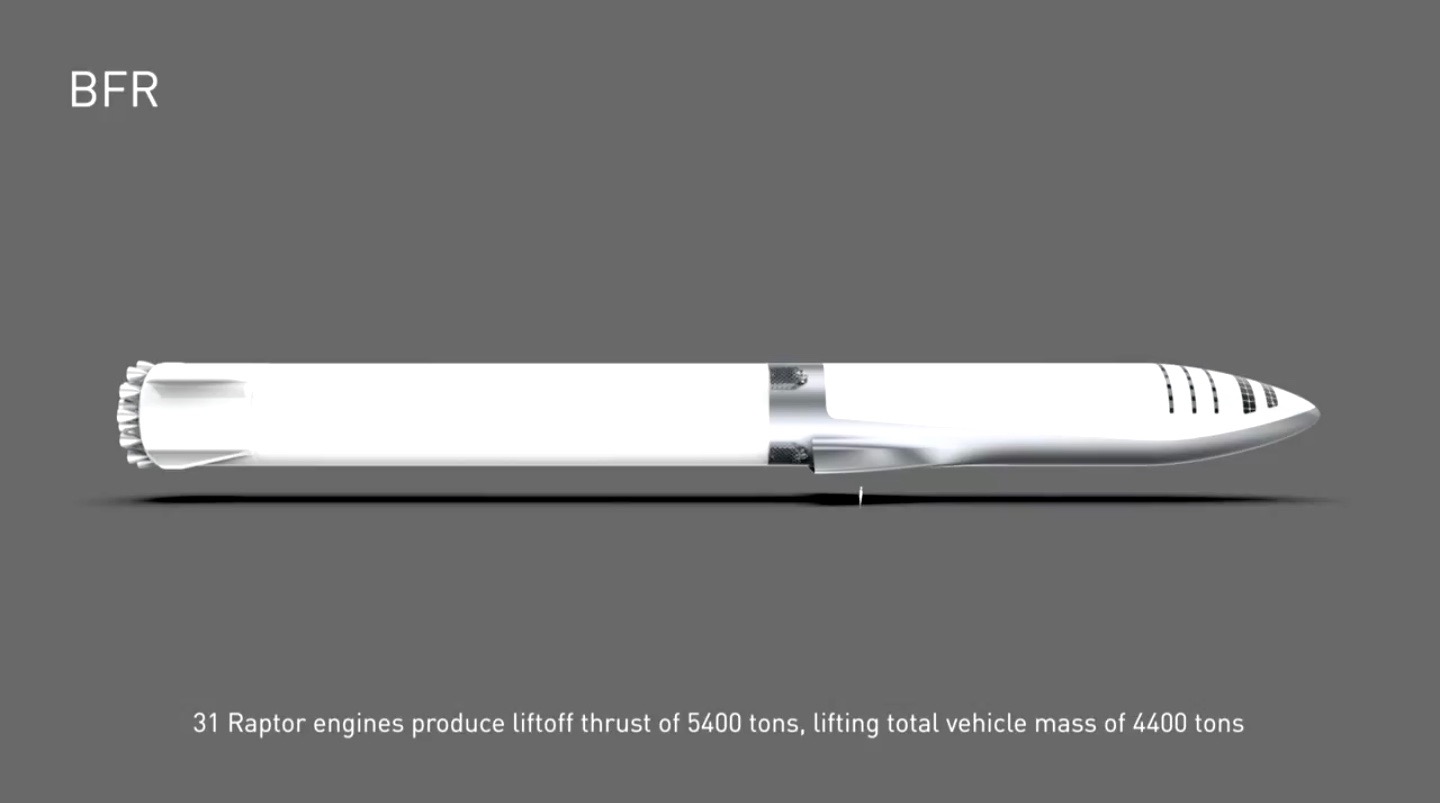

On paper, SpaceX's Big Falcon Rocket looks like the megarocket to end all megarockets. It's a completely reusable launch system and features a massive spaceship on top of an equally massive booster powered by 31 SpaceX Raptor engines. (The Falcon Heavy uses 27 of the company's Merlin engines.) [The BFR: SpaceX's Mars-Colonization Architecture in Images]

The combined rocket and spaceship will stand 348 feet (106 meters) and will be able to launch 150 tons (136 metric tons) to low Earth orbit (LEO), making the BFR more powerful than NASA's Saturn V moon rocket, which could launch 135 tons (122 metric tons) to LEO. (The Falcon Heavy may be the most powerful rocket in operation today, but it would take more than one to match the Saturn V, Musk said.)

Each spaceship may carry up to 100 passengers, and the spacecraft on its own —without the booster —could potentially be used for superfast point-to-point travel around the Earth, Musk said last year when describing the system at the International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia.

This week, Musk said work on the BFR —which he first unveiled to the world in 2016 — has been going so well, the company no longer plans to use its brand-new Falcon Heavy rocket to launch astronauts on deep-space missions.

Last year, Musk announced SpaceX would use the Falcon Heavy and a Crew Dragon capsule to launch two passengers on a trip around the moon. That mission, he said then, could potentially launch by the end of 2018. But now, SpaceX will likely not certify Falcon Heavy to carry astronauts as it has for Falcon 9, and will for the BFR.

Simply put, the BFR is the better choice, Musk said.

"The ship is capable of single-stage to orbit if we fully load the tanks," Musk said of the BFR's spaceship without its booster.

That spaceship could be ready for short demonstration hops in 2019, Musk said. Those hops would be much like SpaceX's prototype Grasshopper rocket tests that led to the reusable Falcon 9 first-stage boosters the company relies on today.

While SpaceX could try to do short hops of the BFR spaceship offshore, flying between its two drone-ship landing pads, it's more likely those tests will occur at the company's newest launch site in south Texas, near Brownsville.

"It will most likely be at our Brownsville location because we've got a lot of land if it blows up," Musk said.

If the BFR test hops are a success, SpaceX would fly a series of ever-more-complex flights to prove out the system, he added.

"I think it's conceivable that we do our first test flight in three or four years," Musk said. That one would send the full BFR system to low Earth orbit.

So that's a big year for SpaceX, with potentially more big years to come. And it's all happening as the company continues its traditional Falcon 9 rocket launches for midsize satellite missions and NASA cargo deliveries to the International Space Station.

The Falcon Heavy debut was SpaceX's third launch of 2018, following two Falcon 9 missions in January that launched the mysterious Zuma payload for the U.S. government and the GovSat-1 communications satellite.

The next mission to fly will be a Falcon 9, launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base, carrying the Paz satellite for the Spanish company Hisdesat. That mission is targeted for Feb. 17, according to Spaceflight Now, and could be followed on Feb. 22 with the launch of another Falcon 9 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station carrying the Hispasat 1F communications satellite for Spain's Hispasat.

Email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or follow him @tariqjmalik and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.