The Next Falcon Heavy Will Carry the Most Powerful Atomic Clock Ever Launched into Space

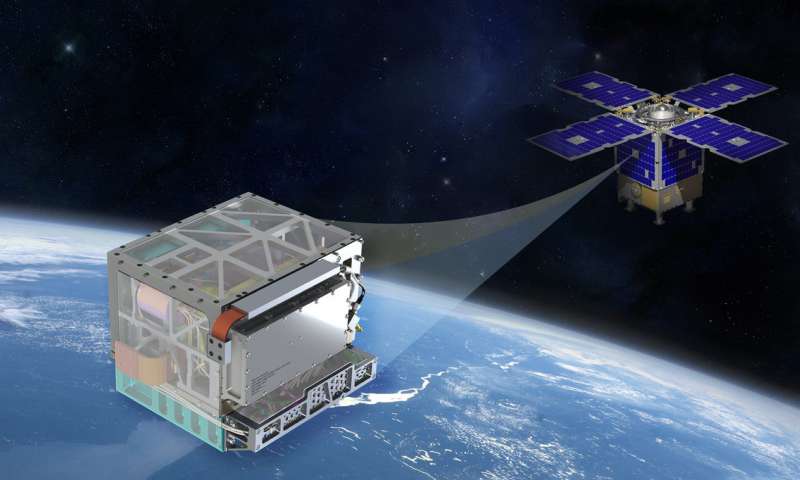

An ultra-precise atomic clock the size of a four-slice toaster is set to zip into outer space this summer, NASA said.

This isn't your average timekeeper. The so-called Deep Space Atomic Clock (DSAC) is far smaller than Earth-bound atomic clocks, far more precise than the handful of other space-bound atomic clocks, and more resilient against the stresses of space travel than any clock ever made. According to a NASA statement, it's expected to lose no more than 2 nanoseconds (2 billionths of a second) over the course of a day. That comes to about 7 millionths of a second over the course of a decade. [5 of the Most Precise Clocks Ever Made]

In an email to Live Science, Andrew Good, a Jet Propulsion Laboratory representative, said the first DSAC will hitch a ride on the second Falcon Heavy launch, scheduled for June. [5 Everyday Things that Are Radioactive]

Atomic clocks are the most powerful time-measuring devices human beings have ever built. Broadly speaking, they work by observing atoms that are known to do certain things — like emit light — extremely regularly and quickly, then counting how many times those atoms do those things. The most powerful atomic clocks on Earth can go billions of years without losing a second of time.

And measuring time extremely precisely is a big deal. All sorts of scientific experiments rely on measuring fractions of a second without errors. The Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite network wouldn't work without precise measurements of the time it takes radio signals to bounce around. And spacecraft beyond Earth's orbit rely on Earth-bound atomic clocks and radio signals to precisely determine their location in space and make course adjustments.

Every deep-space mission that makes course corrections needs to send signals to ground stations on Earth. Those ground stations rely on atomic clocks to measure just how long those signals took to arrive, which allows them to locate the spacecraft's position down to the meter in the vast vacuum. They then send signals back, telling the craft where they are and where to go next.

That's a cumbersome process, and it means any given ground station can support only one spacecraft at a time. The goal of DSAC, according to a NASA fact sheet, is to allow spacecraft to make precise timing measurements onboard a spacecraft, without waiting for information from Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A DSAC-equipped spacecraft, according to NASA's statement, could calculate time without waiting for measurements from Earth — allowing it to make course adjustments or perform precision science experiments without pausing to turn its antennas earthward and waiting for a reply.

The DSAC relies on a relatively new atomic clock technology, first described in a paper published in 2006, that measures the behavior of a single trapped, laser-cooled mercury ion. That ion "ticks" much faster than the cesium atoms in older atomic clocks, such as the ones that guided official U.S. time for years, or the ones aboard GPS satellites.

The version used for the DSAC is also designed so the clock doesn't lose time under the stresses of launch G-forces or the deep cold of outer space, as well as to draw very little power. And toaster-size isn't the limit, as NASA also wrote in its statement that the clock could be further miniaturized for future missions.

Once launched, the test DSAC will orbit for about a year to test its performance. Down the road, in addition to using it for deep-space missions, NASA wrote that the technology could be used to improve the GPS system.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rafi wrote for Live Science from 2017 until 2021, when he became a technical writer for IBM Quantum. He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill School of journalism. You can find his past science reporting at Inverse, Business Insider and Popular Science, and his past photojournalism on the Flash90 wire service and in the pages of The Courier Post of southern New Jersey.