60 Years! One of NASA's Longest-Serving Women Marks Milestone

This January, one of NASA's longest-serving women celebrated a landmark anniversary with the space agency. Only two days before the United States launched its first satellite, Explorer 1, in 1958, Sue Finley started what would be a long career at Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Sixty years later, the 81-year-old still works at JPL.

"I'm happy here every day," Finley told Space.com. Over six decades, she has worked on a vast array of missions, from the Mariner satellites that visited Mars in the 1970s to Juno, the mission currently orbiting Jupiter. She loves the work and the people, both of which contribute to an enjoyable work environment, she said.

"I have been extremely lucky," she said. "It has always been that way here." [The Women Computers of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Slideshow)]

A lab in the mountains

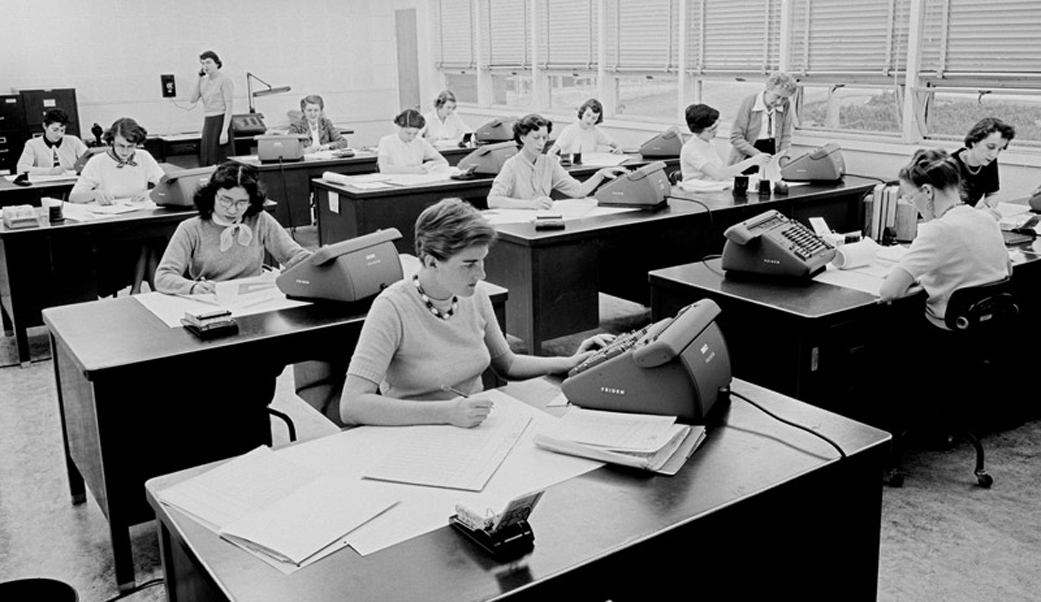

Finley took an improbable path to working on spacecraft. She spent three years in college studying art with the goal of becoming an architect. After becoming frustrated when she found that her credits wouldn't transfer to an architect school, she applied to work at an engineering company as a typist. That company was hiring computers — at that time, the term for a person (usually a woman) who calculated vast swaths of numbers for engineers.

"They asked me how I liked math," Finley said. "I said I liked it much better than letters."

She didn't do all the calculations in her head. Using a large Friden calculating machine, she and another woman punched in the numbers for 40 engineers.

After only a few months, Finley married and moved, and the commute to the company became too much for her. Her new husband had graduated from the nearby California Institute of Technology (Caltech), which today manages the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) on behalf of NASA.

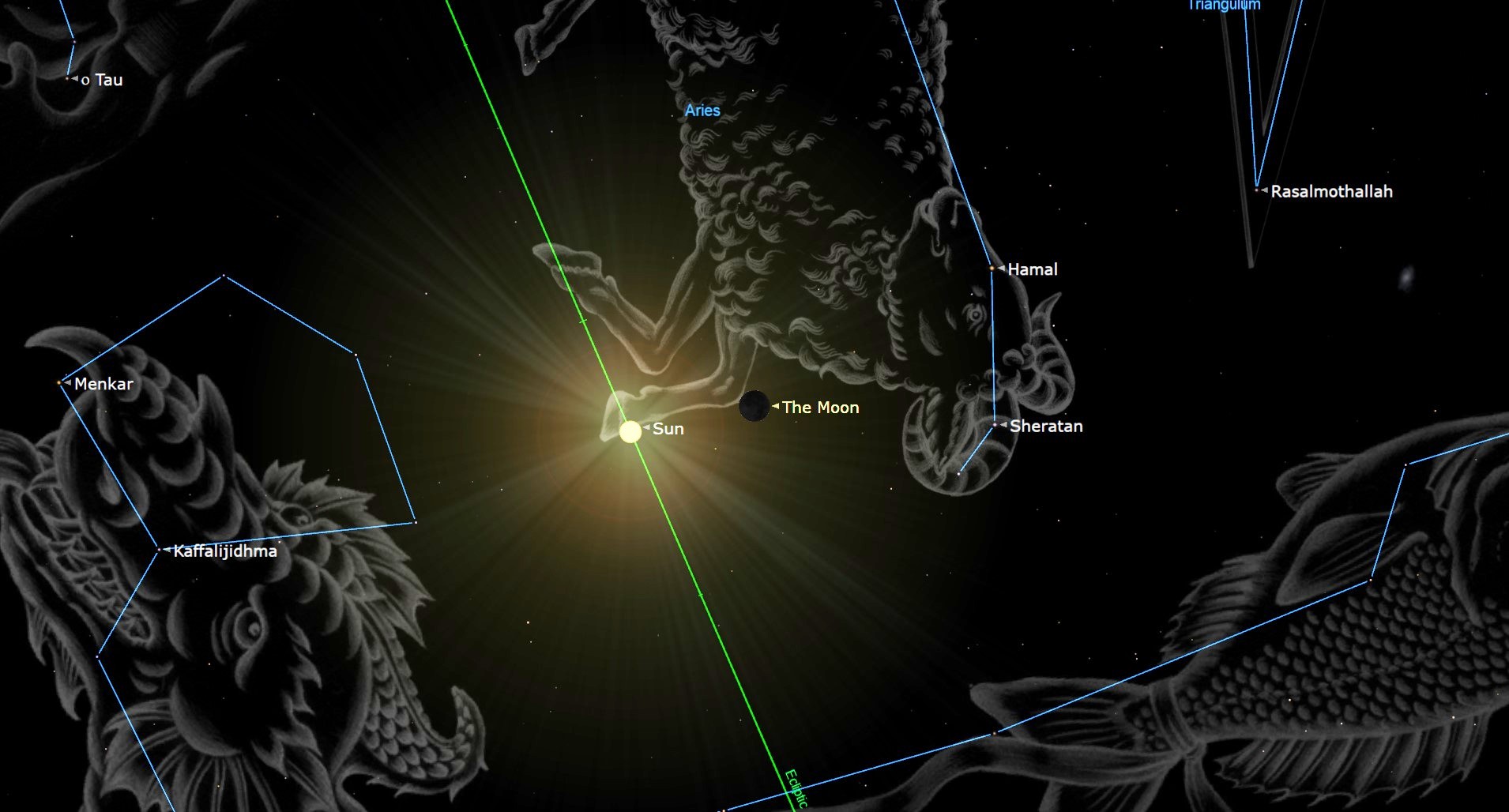

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"He knew that there was a lab up in the mountains I should go and apply to," she said.

Located in an isolated area next to the San Gabriel Mountains, the lab was started by a group of Caltech students and amateur rocket enthusiasts. They needed somewhere to tinker with rockets without disturbing the local population. When Finley applied to the lab in 1958, it was sponsored by the U.S. Army; NASA wouldn't form until that October.

Luck played a big role in getting her where she is today, she said. Referring to her lack of a college degree, she said, "I'd never get hired these days."

JPL was making strides even without the help of NASA's predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. In January 1958, JPL launched the United States' first satellite. Finley started only a few days before the launch, and never got to work on the history-making mission.

"I wouldn't have known what to do after two days," she laughed.

Finley worked at JPL for three years before she took off to help her husband obtain his master's degree. During her hiatus, she took a free class in programming. When she returned to JPL, her ability helped her make the jump from human computer to programmer. From there, she began using the programming language Fortran to work with a new computing machine, a predecessor to today's digital computers.

"It was pretty much the same, just a different machine," Finley said. "And we used punch cards instead of punching the numbers in ourselves."

After another year and a half at JPL, she took off six years to "have two boys and get them on their way." Both of her children have grown up and now work in computer-related fields.

"It's in the genes," she said. ['Rise of the Rocket Girls' Tells the Stories of NASA's Women Pioneers]

A long career

Finley worked as a programmer making calculations for spacecraft navigation for several years, she said. In the 1980s, she moved over to work with the Deep Space Network (DSN). The DSN provides a constant link to missions in space with three stations around the world, each separated by roughly 120 degrees of longitude. NASA and other agencies use the network to send home the data collected by missions.

"If it weren't for the DSN, there wouldn't be any science done, because nobody could listen to [the spacecraft]," Finley said.

She also worked with several missions on their entry, descent and landing tones. As a spacecraft approaches its planet, its more-powerful antennas typically are not pointed back toward Earth. Instead, some craft carry a weaker antenna that broadcasts tones of varying frequency, with each tone signaling a different report back to Earth.

"If everything goes well, it sends the correct tones and everybody's happy," she said.

The first mission to broadcast these real-time tones was Mars Pathfinder, which carried Sojourner, the first Martian rover. Finley said that the tones worked so well that NASA decided to use them on all of the more-expensive spacecraft. She said that all of the Mars rovers broadcast these tones, as does Juno. The Mars 2020 mission and Europa Clipper satellite also plan to send back tones.

So far, Finley said, all of the missions carrying tones have been successful. It wasn't until missions like the Mars Polar Lander (MPL) failed that mission designers recognized how useful the tones could be. When the lander, headed for Mars' south pole, crashed into the planet's surface, broadcast tones would have told engineers what had gone wrong in the mission's final few minutes. Instead, it took much longer for NASA to determine that the most likely cause of the crash came from a software error mis-identifying vibrations during descent, then shutting down the engines 130 feet (40 meters) above the surface. The official report on the loss of the lander concluded that the omission of tones was "not justifiable in the context of MPL as one element of the ongoing Mars exploration program."

Her favorite mission out of all the ones she has worked on, she said, was the Soviet-French Venera-Gallei (Vega) mission, which dropped survey balloons into the atmosphere of Venus. As part of an international tracking network organized by the French space agency, CNES, the DSN's antennas communicated with the satellite as the spacecraft traveled through space. The antennas also received signals from the balloons on the Venusian surface over the objects' two-day lifetime.

Finley said she enjoyed that the mission required only a small team at JPL.

"Everything I did was important. Nobody else could do it," she said. "That's a good situation to be in, although it's high pressure." ['Women of NASA' Lego Set: Q&A with Creator Maia Weinstock]

"This old girl is still here!"

Over her 60 years of off-and-on work at JPL, Finley has seen many things change, she said.

"Of course, there's infinitely more bureaucracy, infinitely more paperwork [now]," she said. Scientific and technological advances have added to that paperwork. "We can get much more done now, but we have much more to do."

Another clear sign of the times is the increased number of female scientists and engineers. "There are a lot more women now," she said.

In her experience, treatment of female programmers hasn't changed, and that's a good thing, Finley said.

"My personal experience has always been that I was treated as an equal colleague, even when I didn't have an education," she said. While women secretaries at JPL weren't given that status when Finley started, "the women engineers have always been treated well."

Another change she has seen is the addition of a childcare center at JPL for parents of young children, something that didn't exist when her sons were young.

"It was certainly my biggest problem," she said.

She said she would advise young women who want to advance as engineers that they should never be afraid to ask questions. Many of the female engineers, as well as the men, don't like to admit when they don't know the answers, Finley said. She credits her success in part to her willingness to inquire.

"That's how I get things done. I have to answer questions," she said. "I have to ask a million questions."

For both men and women, she advised, "Never be afraid to say you don't know — but then go find out."

Finley said that the number of female managers at JPL has also increased over her time there.

"Probably because the 'old boy network' has gotten too old and isn't here anymore," she said.

"But this old girl is still here!"

No sign of retirement

Finley celebrated her 81st birthday in October, but said she has no plans to retire.

"Financially, I always figured I had to work until I was at least 70," she said. Then, NASA's Juno mission came along, and she committed to sticking around until the satellite entered orbit around Jupiter, which the spacecraft did on July 5, 2016.

Now, she's committed to getting the DSN's new antennas online, she said. Although she's traveled to the stations in California, Spain and Australia frequently in her career, she said she isn't traveling as much these days. The 70-meter (230 feet) antennas located at each site are supposed to be replaced by four 34-m (112 feet) antennas by 2025.

"There just seems to be something in the future always that they want me to do," she said. "And there's nothing at home that I want to do."

Finley is one of the longest-serving NASA women, according to Andrew Good, a media relations specialist at JPL. Her career illustrates why it is so difficult to pick out a single person who can claim to have had the longest career, he said.

"Honestly, I'm not sure there's any way to know," Good said. That's because you'd have to have a full account of every female employee who ever worked at any of the 10 NASA centers. Like Finley, many of them took time off to raise children, he said. And like her, quite a few started working at NASA centers before the agency formed, in October 1958.

Still, Finley plans to keep going at NASA, she said.

"My boss says I can't retire until he does," she joked. "He'll retire in 22 years."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd