Pac-Man' and 'Mario Kart': How to Understand Planet Formation

NEW YORK — On a chilly February night, astronomy enthusiasts of all ages gathered inside the Kaufmann Theater within the American Museum of Natural History for a special after-hours event. They made their way past sculptures invoking Jupiter and Mercury, which offered reminders that planets, albeit much more distant ones, would be E.T.'s subject. Yes, the lecture on alien worlds was led by a person with those initials, and it was the delightful first joke of the night.

E.T. — short for Elizabeth Tasker, a researcher at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency — took the stage in New York on Feb. 5 to break down the many colorful theories of how alien planets form and how to find them as explored in her new book, "The Planet Factory: Exoplanets and the Search for a Second Earth" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2017).[TRAPPIST-1 Planets Could Harbor 250 Times More Water Than Earth's Oceans]

There have been several recent mind-blowing exoplanet discoveries: the many worlds orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1 — some of which could have liquid water — and surprising "hot-Jupiter" gas giants orbiting very close to their parent stars shatter the idea that our solar system is the only planetary setup.

Creative references to video games like "Pac-Man" and "Mario Kart" were highlights of the "Dangerous Worlds" lecture. Oh, and there was also a brief but memorable mention of a highly toxic gas used in early exoplanet detection.

"The 1990s is scarily recent, at least I still think it is," Tasker said. "Why did it take us so long to find planets around other stars? It's not like we didn't think they'd be there."

"The problem with stars is that they're really big and they're really bright, and planets are really scriffy and really dim, so it's super hard to see them at a big distance," she added.

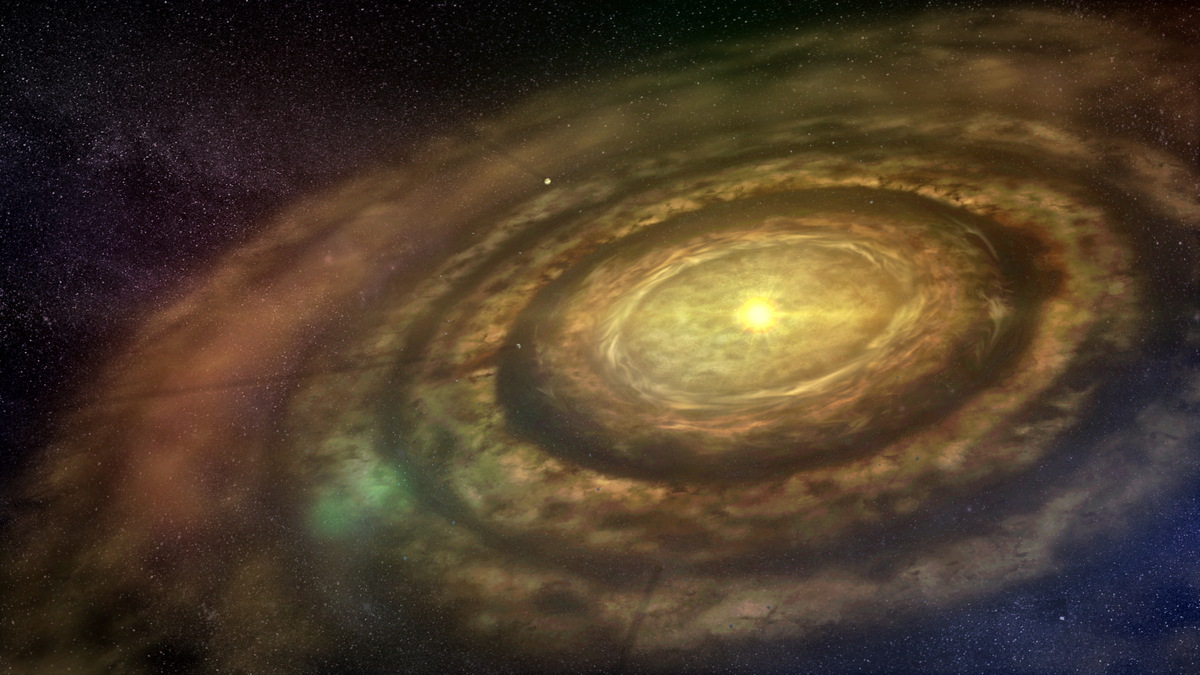

The "'Pac-Man' stage" of planetary formation is, in Tasker's words, when a young planet is "munching up" the small rocks near itself. The planet and rocks are traveling about the same speed, and when the rocks make contact, they stick and the young planet gets "fatter." Over time, the planet's gravitational pull increases and its orbit can eventually make its parent star wobble. An early method of finding exoplanets relied on detecting a star's slight movement, and gas cylinders offered an early hack to identify the tiny change.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What people did was they put a jar of gas in front of this telescope…it was like slamming a ruler right in front of your starlight," Tasker said. The gravitational pull of a planet made its parent star wobble ever so slightly, and this jar of gas "made a tiny shift much easier to measure." The gas emits a light little of its own at a constant rate, so by passing starlight through it, the gas served as a comparison point and wobbling in small stars could be observed.

But the gas was so potent, it ate through the jar. "Now the original contents of the gas cylinder was hydrogen fluoride, which is immensely toxic. In fact, it's so toxic that it used to corrode the gas cylinder, and so between observations, the only solution was for astronomers to, by hand, go to this incredibly toxic gas…and change it for the next observation," Tasker said. "They don't use the same gas now."

Tasker used a simulation drawn from the racing game "Mario Kart" to explain why planets sometimes migrate when they're forming. To show how gas giant planets end up so close to their parent stars when they are born in a cooler part of the protoplanetary disk, Tasker imagined a circular racetrack: the character Yoshi in the innermost track, Mario in the middle lane and Princess Peach in the outermost track. They're zooming around a hypothetical parent star at the center, and all three Karts are attached to one another by a string. The string demonstrates the gravitational tug that big clumps of stuff can have on a forming gas planet (Mario) from different directions. [Super-Earth' Alien Worlds May Carve Up Planet-Forming Disks]

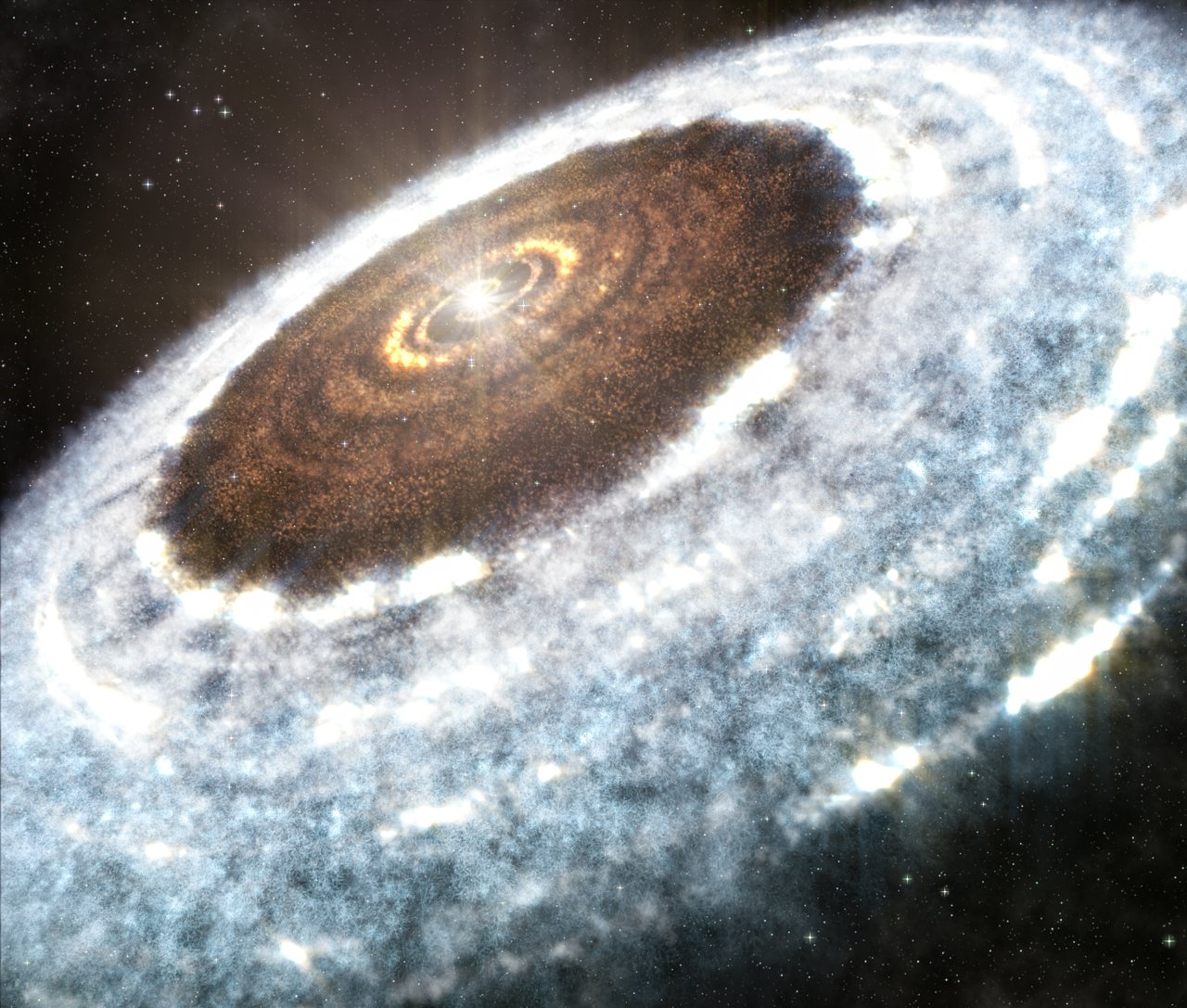

In the case of hot Jupiters, the gas planet forms beyond the ice line (where the radiation released by a star has weakened enough for water to freeze). Tasker said that after gobbling up silicates and ices in its Pac-Man stage, the gas giant planet is lured in closer to the star by dust and gas. And in the case of the solar system, the process explains why Jupiter is so big, and Mars is surprisingly small.

Some astronomers believe Jupiter was once closer to the sun while it was growing, clearing out all the little rocks known as planetesimals. "Now as it does this, Saturn appears, and Saturn also starts beefing up and starts to migrate inwards."

"At this point, you have a lot of forces going on," Tasker said of the solar system formation process. "You still got that gas drag trying to pull you inwards, but now that gravity of each other is going to pull. And if you sum together all these rather complex forces, strangely enough, you do a U-turn. And the two [Jupiter and Saturn] start to move back out, and we call this the Grand Tack model. Because you go in, you do a turn, and come out. So in that case, these two planets move back out."

But this spells doom for Mars, which ends up, in Tasker's humorous take, "pathetic."

"Now after this happens, our little terrestrial worlds start forming, and that's just dandy for Mercury, Venus, Earth. But poor old Mars has had all its rocks eaten by Jupiter."

You can buy Tasker's book, "Planet Factory: Exoplanets and the Search for a Second Earth," on Amazon.com.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.