The Curiosity Rover Just Drilled into a Rock on Mars for 1st Time Since 2016

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity just drilled into a Red Planet rock for the first time in more than a year.

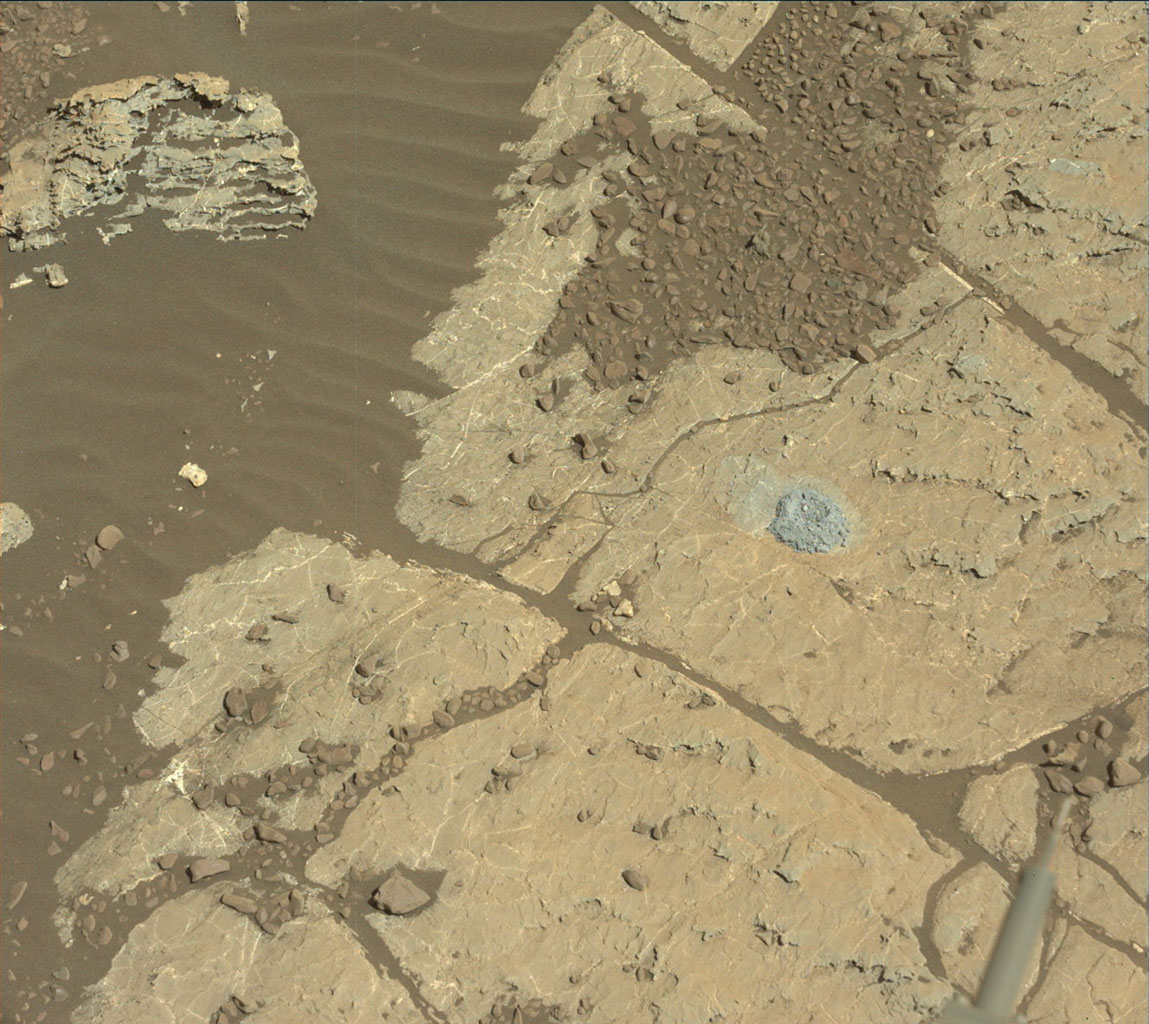

Curiosity bored a hole about 0.5 inches (1.3 centimeters) deep into a target rock on Monday (Feb. 26), during the trial run of a new, jury-rigged drilling technique, NASA officials said.

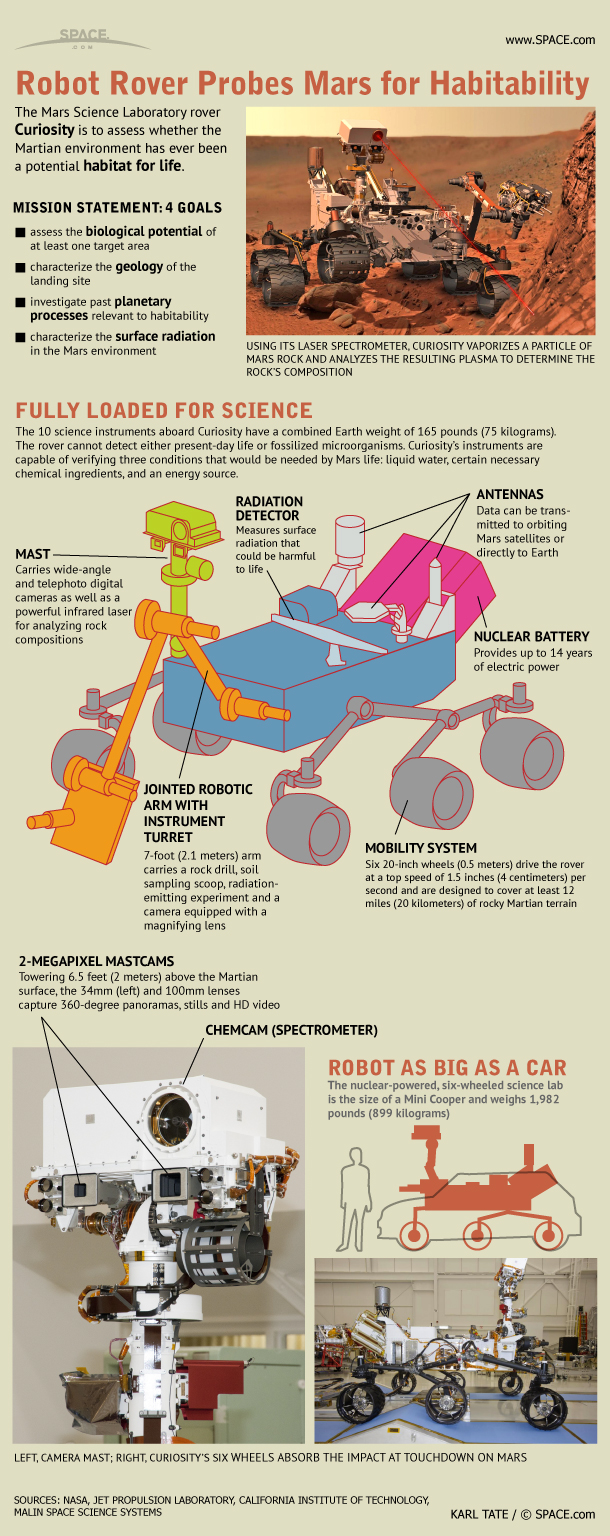

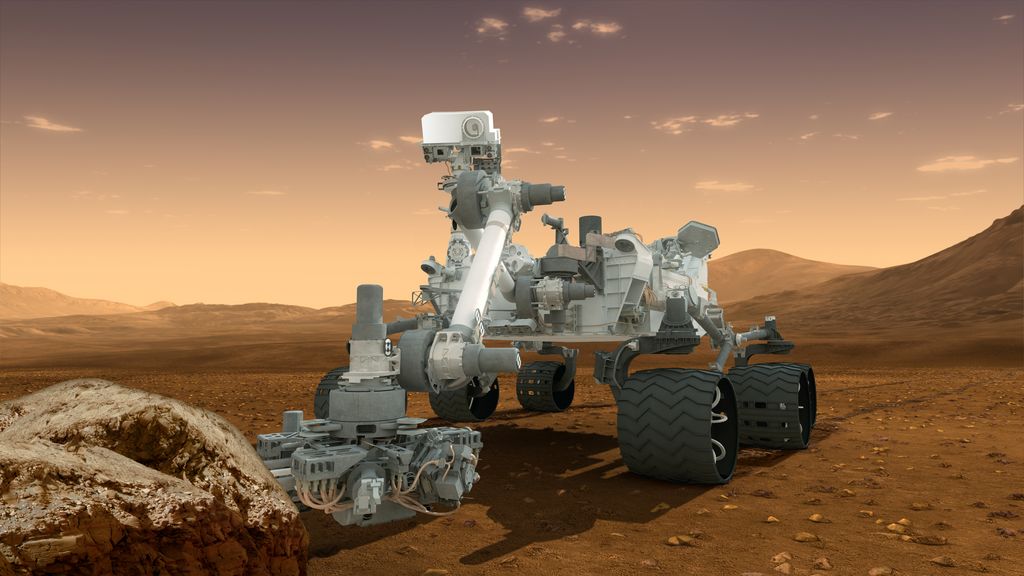

The car-size rover's drill — a key tool at the end of Curiosity's robotic arm that allows it to snag pristine samples from the interiors of ancient rocks — has been out of commission since late 2016, when a motor that extends two stabilizing posts on either side of the drill bit conked out. [Photos: Spectacular Mars Vistas by NASA's Curiosity Rover]

Engineers have been working for the past 15 months to bring the drill back online. They've settled on a strategy that involves extending the bit out beyond the stabilizers, and carefully pushing it against a rock using Curiosity's arm. The rover can keep the drill bit centered using a force sensor, mission team members said.

"We're now drilling on Mars more like the way you do at home," Curiosity deputy project manager Steven Lee, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "Humans are pretty good at re-centering the drill, almost without thinking about it. Programming Curiosity to do this by itself was challenging — especially when it wasn't designed to do that."

Tests at JPL with Curiosity's ground-bound twin went well, so the mission team took the new strategy into the Martian field Monday. The results were encouraging, NASA officials said, but the drill is not back in operational mode yet.

For example, the test hole wasn't deep enough to let Curiosity grab samples. (During its original run, the rover's drill routinely bored 2.5 inches, or 6.5 cm, down into rocks.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And Curiosity will have to bag up those samples in a new way from now on: With the drill permanently extended, the rover cannot use the associated instrument designed to deliver rock powder to two powerful onboard laboratories, known as Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) and Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin), NASA officials said. Instead, Curiosity will sprinkle the powder from the drill bit into SAM and CheMin.

"This tapping has been successfully tested here on Earth — but Earth's atmosphere and gravity are very different from that of Mars," NASA officials wrote in the same statement. "Whether rock powder on Mars will fall out in the same volume and in a controlled way has yet to be seen."

Curiosity touched down on the floor of the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater in August 2012, on a $2.5 billion mission to investigate Mars' past ability to support microbial life. The rover's observations quickly established that Gale harbored a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system in the ancient past.

In September 2014, Curiosity reached the base of Mount Sharp, which towers 3.4 miles high (5.5 km) into the Red Planet's sky from Gale's center. The rover has been working its way up the mountain ever since, hunting for clues about Mars' long-ago transition from a relatively warm and wet world to an arid, dry planet.

Curiosity is currently studying a landform called Vera Rubin Ridge, which lies about 1,000 vertical feet (300 meters) above the crater floor.

To date, the rover has collected samples using its drill 15 times, with the last such activity occurring in late 2016. Since the drill problem arose, Curiosity has pushed the extended bit against rock as part of troubleshooting tests, but Monday's action marked the first actual drilling using the new technique, NASA officials said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.