An Even-Weirder-Than-Usual Tardigrade Just Turned Up in a Parking Lot

A newfound species of tardigrade, or "water bear," with tendril-festooned eggs has been discovered in the parking lot of an apartment building in Japan.

The newfound tardigrade, Macrobiotus shonaicus, is the 168th species of this sturdy micro-animal ever discovered in Japan. Tardigrades are famous for their toughness: They can survive in extreme cold (down to minus 328 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 200 Celsius), extreme heat (more than 300 degrees F, or 149 degrees C), and even the unrelenting radiation and vacuum of space, as one 2008 study reported.

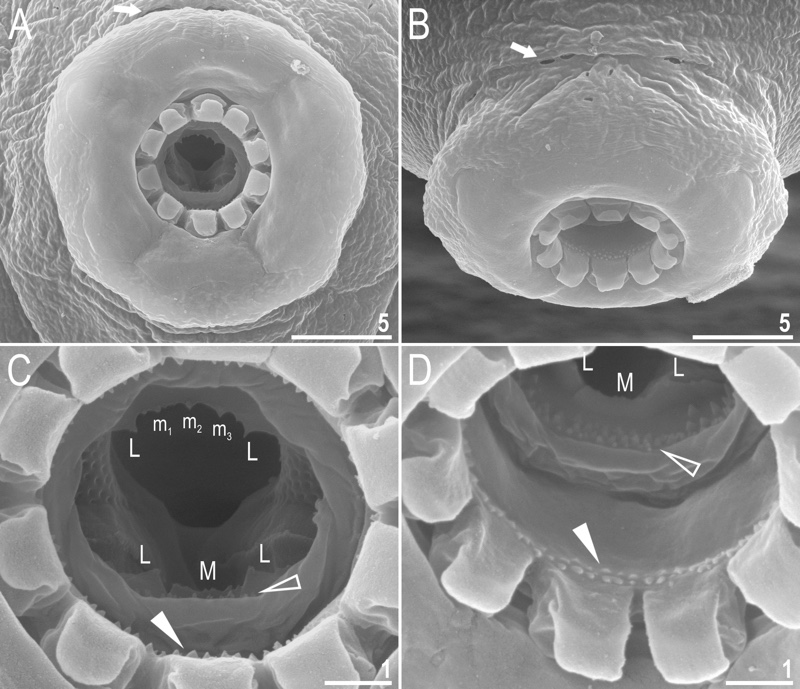

They're bizarre and adorable at the same time, with eight legs on a rotund little body (they're usually far less than a millimeter in length) and circular mouths that make them look perpetually surprised.

Kazuharu Arakawa, a researcher who studies the molecular biology of tardigrades at Japan's Keio University, discovered the newfound species in a small sample of moss. He'd scraped the moss from the parking lot of his apartment in Tsuruoka City along the Sea of Japan. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"Most of [the] tardigrade species were described from mosses and lichens — thus any cushion of moss seems to be interesting for people working on tardigrades," Arakawa told Live Science in an email. But, he said, "it was quite surprising to find a new species around my apartment!"

Spaghetti eggs

Arakawa routinely samples moss he finds around town, he said, but the portion from his parking lot turned out to be special. The tardigrades he found there could survive and reproduce in a laboratory environment, which is very rare for these creatures, he said.

He sequenced the tiny animal's genome and only then realized that it matched no previously found tardigrade sequence. Arakawa looped in tardigrade expert Łukasz Michalczyk of Jagiellonian University in Poland, and the researchers determined that they had a newfound species on their hands.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The species ranges in length from 318 micrometers to 743 micrometers. It has the typical plump-caterpillar look of a tardigrade, and its O-shaped mouth is ringed by three rows of teeth. It can live on algae, which is odd because other species in the Macrobiotus genus are carnivores that eat even tinier animals called rotifers, Arakawa said. [In Photos: The World's Freakiest Looking Animals]

Perhaps the weirdest aspect of M. shonaicus, though, is its eggs. The spherical eggs are studded with miniscule, chalice-shaped protrusions, each of which is topped with a ring of delicate, noodle-like filaments. These features might help the egg attach to the surface where it is laid, Arakawa said.

Tardigrade family tree

The newfound species is part of a set of tardigrade species, known as the hufelandi group, that all have these cup-like egg decorations, Arakawa and his team reported today (Feb. 28) in the open-access journal PLOS One. Macrobiotus hufelandi was the first tardigrade species ever discovered, way back in 1834. That species was found in Italy and Germany originally, but it and its close relatives have now been found all over the globe, Arakawa said.

"This is the first report of a new species in this complex from East Asia," he said. More tardigrade-hunting is necessary to find out how tardigrades diversified and adapted over time, he said.

Also exciting is that M. shonaicus can thrive in the lab, Arakawa said.

"It is an ideal model to study the sexual-reproduction machinery and behaviors of tardigrades," he said. "We are actually already submitting another paper describing their mating behaviors."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.