Biggest Black Holes May Grow Faster Than Host Galaxies

Some of the most monstrous black holes in the universe are growing faster than their host galaxies, new research suggests.

Supermassive black holes are believed to exist at the centers of most, if not all, large galaxies, where they feed on surrounding gas, dust and other material. Two new studies suggest that these massive black holes are much bigger than expected based on the rate at which surrounding stars are forming, the researchers said.

"We are trying to reconstruct a race that started billions of years ago," Guang Yang, a researcher at Penn State and lead author of one of the studies, said in a statement. "We are using extraordinary data taken from different telescopes to figure out how this cosmic competition unfolded." [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

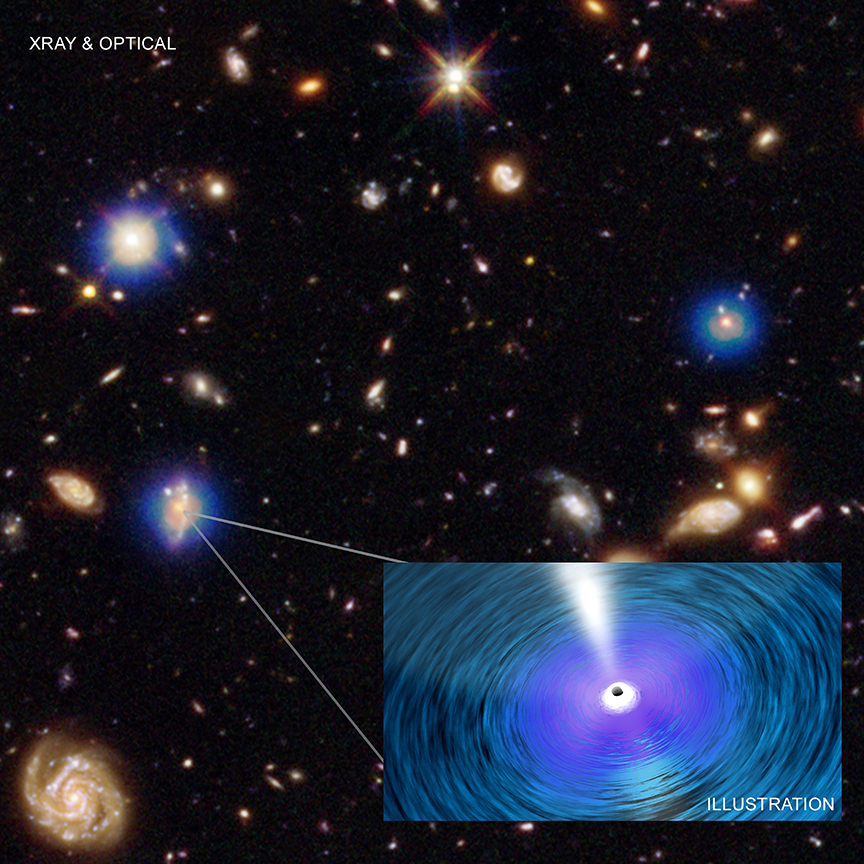

Using data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes, Yang's study examined the rate at which black holes grow in galaxies located 4.3 billion to 12.2 billion light-years from Earth. The researchers compared the growth rate of a black hole to the growth rate of stars in the host galaxy.

Earlier research has suggested that black holes and the stars in their host galaxies generally grow in tandem with each other. However, the new findings, which are available on arXiv.org and will be published in the April issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, show that the larger the galaxy, the larger the ratio between the growth rate of its black hole and its stars.

"An obvious question is, 'Why'?" Niel Brandt, a researcher at Penn State and co-author of the study, said in the same statement. "Maybe massive galaxies are more effective at feeding cold gas to their central supermassive black holes than less massive ones."

In a second study, which also used Chandra data, a team of researchers found that, in larger galaxies, black holes grow about 10 times faster than the galaxy's stars are formed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We found black holes that are far bigger than we expected," Mar Mezcua, lead author of the second study and a researcher at the Institute of Space Sciences in Barcelona, Spain, said in the statement. "Maybe they got a head start in this race to grow, or maybe they've had an edge in speed of growth that's lasted billions of years."

For that study, the researchers focused on black holes in some of the "brightest and most massive galaxies in the universe," according to the statement. They looked at 72 galaxies at the center of galaxy clusters located up to about 3.5 billion light-years from Earth.

Along with the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the researchers used data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array, the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array and the Very Long Baseline Array. The researchers were able to estimate the masses of the supermassive black holes based on their associated X-ray and radio emissions. The team found that the black holes were about 10 times larger than estimated using traditional methods that assumed that black holes and their galaxies grow in tandem.

Furthermore, almost half of the black holes that the researchers studied weighed in as even bigger "ultramassive" black holes, rather than just supermassive black holes, according to the statement.

Whereas supermassive black holes are generally millions of times heavier than our sun, "ultramassive" black holes are estimated to harbor at least 10 billion solar masses.

"We know that black holes are extreme objects," J. Hlavacek-Larrondo, co-author of the second study and a researcher at the University of Montreal, said in the statement. "So it may not come as a surprise that the most extreme examples of them would break the rules we thought they should follow."

The second study was published Feb. 11 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The full article text is also available on arXiv.org.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.