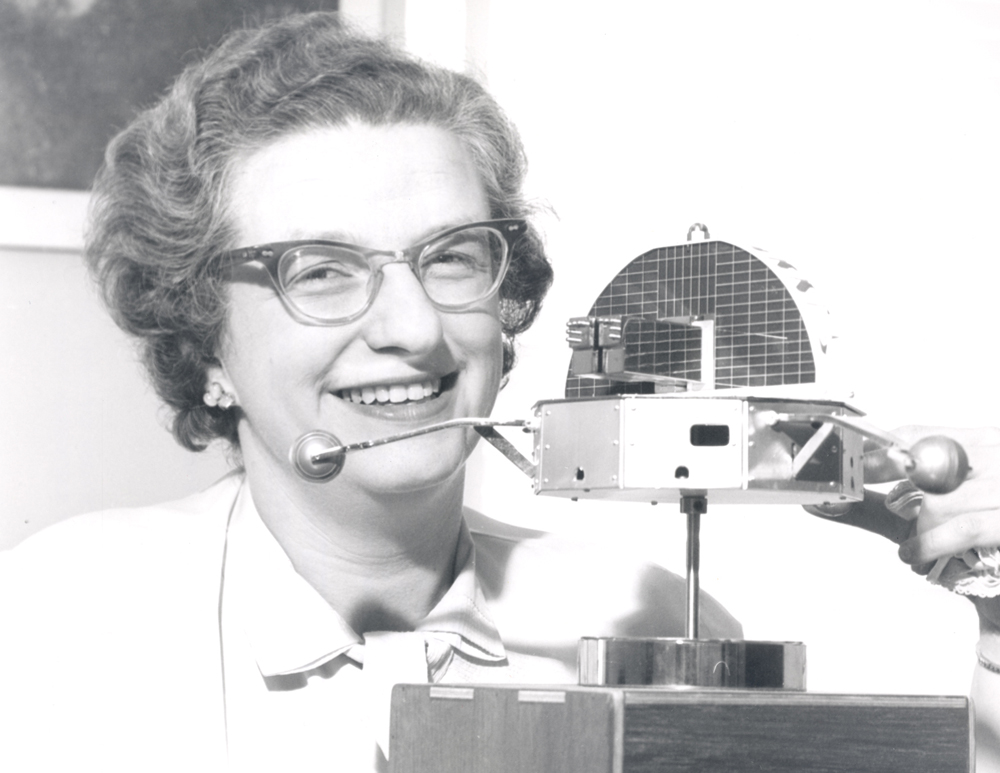

'Mother of Hubble' Nancy Grace Roman Led the Way for Women in Astronomy

At a time when men dominated the field of astronomy, Nancy Grace Roman stepped up to become "the mother of Hubble."

Roman was the first chief of astronomy in the Office of Space Science at NASA Headquarters and the first woman to hold an executive position at the space agency. In her role, she successfully managed a number of astronomy-based projects, including what would eventually become the Hubble Space Telescope.

"The idea of Hubble was something that was among the astronomical community for generations; it was not something that was new," Roman said in a video released by NASA in February. "Astronomers badly wanted a large telescope above the atmosphere." [The Hubble Space Telescope: A 25th Anniversary Photo Celebration]

In the video, Roman discusses how she helped bring light to Hubble, and she talks about the pervasive bias against female scientists that she had to overcome along the way.

Math over Latin

Nancy Grace Roman was born on May 16, 1925, in Nashville, Tennessee. She was the only child of Georgia Frances (Smith) and Irwin Roman. Her father held a joint degree in physics and mathematics, and his work in geophysics meant that he moved frequently in Nancy's early years.

But it's her mother that Roman credits for her interest in astronomy. In a fascinating 1980 oral interview with the American Institute of Physics, Roman said that when the family lived in Michigan, her mother would take her out at night and show her the constellations and the northern lights, as well as plants and animals.

The family lived in Reno, Nevada, for two years when Roman was still young. The second summer she was there, when she was about 11, she started an astronomy club with the girls in the neighborhood.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In her early high school days, Roman made the deliberate decision to go into astronomy, despite the long period of education it would require. She decided that if it didn't work out as a career, she could teach physics and mathematics to high school students.

"I don't know exactly at what age it was, but I do remember it was a conscious decision on my part," Roman said in the oral interview.

While her parents were both supportive, she didn't receive a lot of outside encouragement.

"I was told from the beginning that a woman could not be an astronomer," she said in the NASA video.

In fact, when she asked her high school counselor for permission to take a second year of algebra instead of a fifth year of Latin, the response was scathing.

"She looked down her nose at me and sneered, 'What lady would take mathematics instead of Latin?'" Roman said. [Women in Space: A Gallery of Firsts]

In 1946, Roman received her bachelor's degree from Swarthmore College, which she said she selected because it had a decent astronomy department at the time. Swarthmore was where she received her first encouragement regarding astronomy, when the head of the physics department told her that he usually tried to talk women out of going into physics. "But I think maybe you might make it," he said.

Roman went on to pursue her doctorate from the University of Chicago. But her thesis adviser there was not exactly supportive.

"There was a period in which he went for six months without speaking to me, even when I said hello to him in the hall," Roman said in the video. "He didn't want anything to do with me."

In the oral interview, she said that may have been part of the reason the department pushed her to leave without completing her degree, recommending her for a teaching position at Vassar College in New York.

Ironically, once she completed her doctorate in 1949, the same professor didn't want her to leave. Roman remained at the University of Chicago, working at its Yerkes Observatory before becoming an instructor and then an assistant professor. Despite such successes, she didn't think that she would be offered a tenured position.

"Right or wrong, I didn't think that I, as a woman, had a chance at tenure," Roman said in her oral interview. "I just didn't think I had a chance. I may be wrong, but I don't think so."

She moved on to the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) for several years, studying radio astronomy. Then, in 1959, a talk by chemist Harold Urey triggered her interest, resulting in a conversation that would change her career.

"One of the team"

The United States consolidated its space operations in October 1958, replacing the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics with a new agency called NASA.

After the Urey talk, Roman was approached by a colleague who had once been at NRL but was now at the newborn NASA. He asked her if she knew anyone who would like to set up NASA's program in space astronomy.

"The idea of coming in with an absolutely clean slate to set up a program that I thought was likely to influence astronomy for 50 years was just a challenge I couldn't turn down," Roman said in the oral interview.

In 1959, Roman became the first chief of astronomy in the Office of Space Science at NASA Headquarters, and the first woman to hold an executive position at NASA.

Paradoxically, she was hired as a fresh doctoral student, despite her years of experience and international reputation. She said that was because her previous salary was so low that the civil service did not recognize her work to that point as professional experience.

Despite being a female astronomer in a crowd of men, Roman said that she had no problems with her NASA colleagues.

"I was accepted very readily as a scientist in my job," she said in the video. "The men were very cooperative, and I felt that the men treated me as one of the team without a problem."

The "Mother of Hubble"

In the years she spent at NASA, Roman was involved in multiple projects. One of them was known as Space Telescope, a massive instrument proposed to orbit Earth and capture data without interference from the planet's atmosphere.

Astronomer Lyman Spitzer hatched the idea of an optical space telescope in 1946. But he faced years of rejection, due in part to the cost as well as the technological challenges.

Eventually, the space-telescope idea came to Roman's attention. She took a practical approach to bring the project together.

"If the aerospace companies were going to put a lot of money into designing a telescope, they might as well design one that made sense," she said in the video.

In 1960, Roman brought together astronomers from all over the country who represented the interests of the astronomical community. She sat them down with NASA engineers and had the two groups hammer out a design for an instrument that could gather the data the science community desired.

Roman and her colleagues met several times to discuss what was then known as the Large Space Telescope. Once other programs, such as Gemini, Apollo and Mariner, began to generate a wealth of space-engineering data, Roman became a strong NASA advocate for what would eventually become the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble launched in April 1990 and continues to make important observations and discoveries today.

"She made it possible to get early telescopes up [into space] to learn what needed to be learned," science historian Bob Zimmerman told Space.com back in 2009. "As soon as that technology started to mature, she was pushing for the design work. Her hard-nosed nature helped get the telescope built." [Hubble in Pictures: Astronomers' Top Picks (Photos)]

Roman retired from NASA in 1969, though she continued to work as a contractor at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland for several years.

But retirement hasn't stopped her from encouraging other women to continue the journey she started so many years ago. On Roman's 90th birthday in 2015, NASA said she continued to speak "eloquently and intelligently with a passion to encourage young women to pursue careers in science and engineering."

"I'm happy about the fact that women can get senior jobs now," Roman said in the video. "They're not being quite as discouraged as I was."

There are still two things she would like to see improve. One is the issue of salaries: According to the Wall Street Journal, female astronomers and physicists earn just 85 percent as much as their male counterparts.

The other issue is the percentage of women in the field. Although changes in attitudes over time have made it easier for women to obtain senior positions in astronomy now than back in Roman's day, she said that there still aren't many women at high levels in the field.

In an earlier interview, as reported by NASA, Roman gave some advice to women who wanted to enter the field of astronomy and work for the space agency.

"My career was quite unusual, so my main advice to someone interested in a career similar to my own is to remain open to change and new opportunities," Roman said. "I like to tell students that the jobs I took after my Ph.D. were not in existence only a few years before. New opportunities can open up for you in this ever-changing field."

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebookor Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd