Gravity Assist Podcast: Science and Science Fiction with Andy Weir

The Gravity Assist Podcast is hosted by NASA's Director of Planetary Science, Jim Green, who each week talks to some of the greatest planetary scientists on the planet, giving a guided tour through the Solar System and beyond in the process. This week, he's joined by author Andy Weir to explore the fascinating intersection of science and science fiction, delving into the biggest surprises about Mars and the Moon, and how Weir's novel, "The Martian," has provided a powerful gravity assist for young readers.

You can listen to the full podcast here, or read the transcript below.

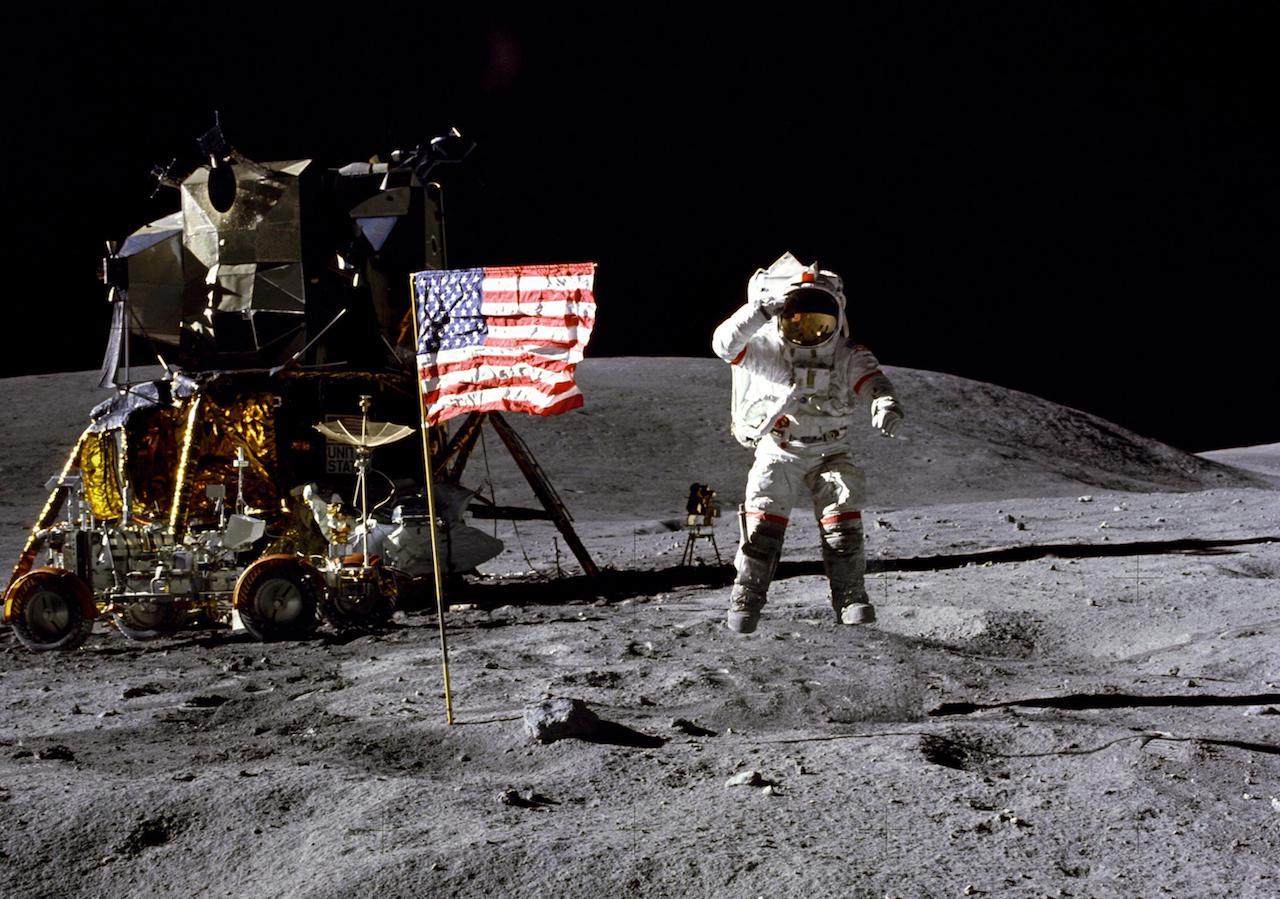

Jim Green: I usually ask this question at the end of an interview, but it seems more appropriate to begin with it. What was your gravity assist, Andy? How has science inspired you to get into writing science fiction?[Making a Moon Base With 'Artemis' Author Andy Weir]

Andy Weir: Well, it was probably through my father — he's a scientist himself. He's a linear accelerator physicist. He's retired now, but he spent his whole career shooting electrons down a tube. He's always been a science dork and a science fiction fan, and he had an inexhaustible supply of science-fiction books in the house for me to read. So, I guess you could say I was indoctrinated from birth.

Jim Green: I see. So, you had an opportunity to read the library. Who were some of your favorite authors?

Andy Weir: Well, my "holy trinity," so to speak, are (Robert) Heinlein, (Isaac) Asimov and (Arthur C.) Clarke. I'm 45 years old, but I grew up reading my father's science fiction collection, reading the juvenile (novels) from the 50s and 60s and early 70s.

Jim Green: They still hold up really well.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Andy Weir: Some of them, yeah. Parts of them don't. Parts of them didn't age well, but other parts of them still hold up really well, especially when they decided to stick with real physics.

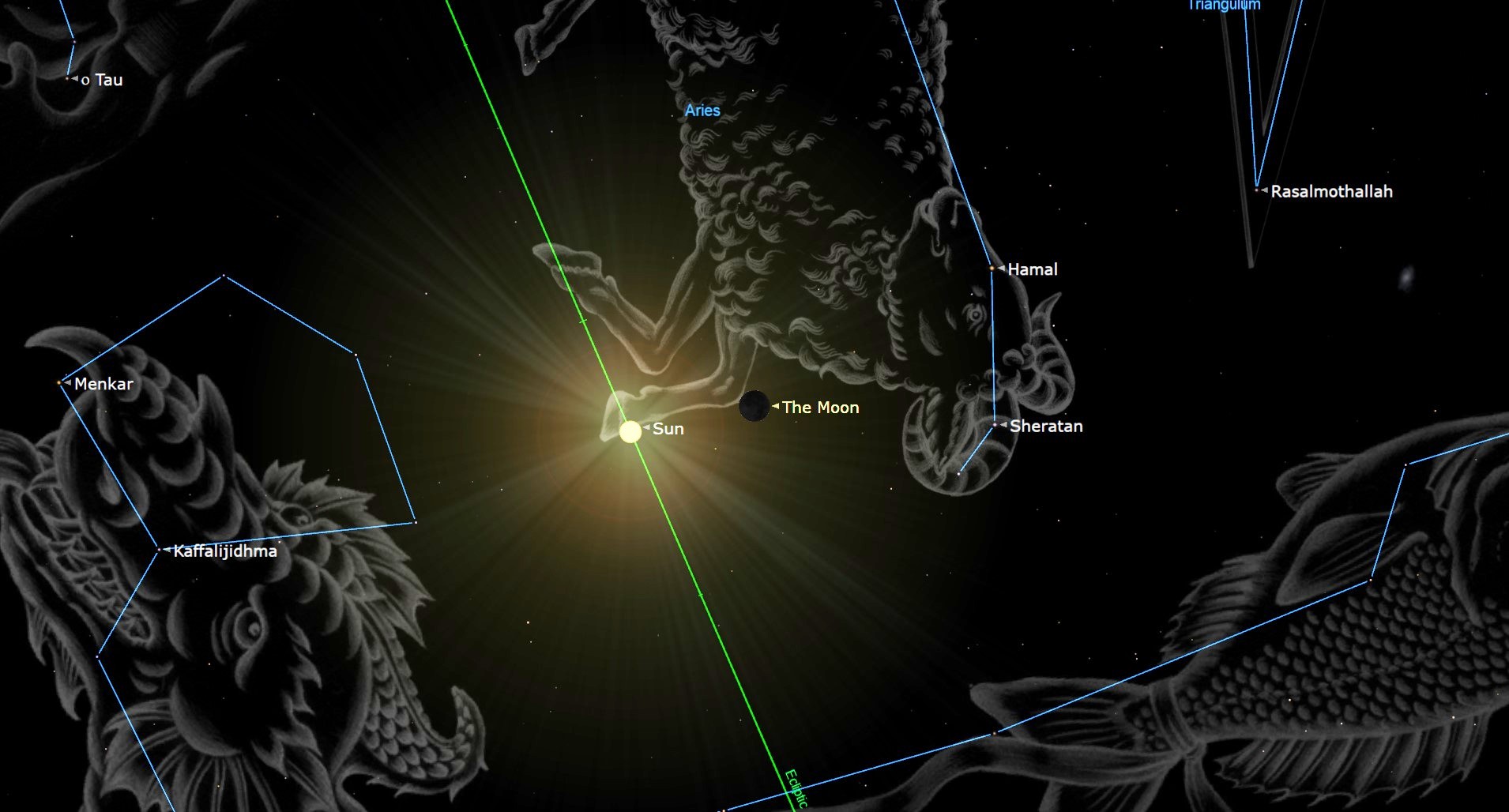

Jim Green: What really surprised you about Mars when you were doing the research for your first book, 'The Martian'?

Andy Weir: I had a lot of fun doing the research, and that's always the part of writing that I enjoy the most. I already knew a lot about it to start with because I've spent my life being a space dork. I feel like I'm in a building where that's very much accepted here at NASA Headquarters in D.C. I've always been into it. So, I started with more than a layman's knowledge of this stuff, but among the things that I discovered while researching Mars that I didn't know before was how fast Phobos' orbit really was, how ludicrously close to the planet it is. It's well within whatever Mars' geosynchronous orbit is called and, in fact, it's nearing the Roche limit, and it's probably going to be a ring in a few hundred thousand years. So, that means that even though Phobos and Deimos both go the same direction around Mars, if you're on the surface of Mars, they appear to be going opposite directions, because Phobos is going around Mars faster than Mars can rotate. That's one thing I found really interesting.

I was also fascinated by Olympus Mons on Mars, the tallest mountain in the Solar System, but it also has an incredibly wide base, almost the size of the state of Texas. The grade is so gradual that the curvature of the planet actually has more of an effect on the horizon than the grade. So, you could be standing on the slopes, for lack of a better word, of Olympus Mons, and you would think you're on a flat plain.

Jim Green: Yeah, it's really spectacular, and this is one of the features that a lot of our scientists point to that says Mars doesn't have plate tectonics. And so, as magma just pokes through the surface, it just sits there and accumulates. But then—

Andy Weir: — Well, I'm going to interrupt you there because recently, within the past year, they [scientists] were able to prove that Mars had an active volcano that lasted on the order of over two billion years, maybe. And the way they were able to prove that is by examining a specific shergottite, a meteorite that had fallen to Earth but originated on Mars. They were able to analyze that and prove that it came from basically the same lava source that these other shergottites came from, and that proved that the same lava source had been active for two billion years. Well, that shergottite that they did the proof with? I have a shergottite at home, a Mars rock at home that was a little gift from me to me with my 'Martian' money. I have it at home and it is that same on, a different piece from the same fall, but it's the same meteorite. So, it was funny when I was reading that news, because of course, I read space news. I was like, it's from this [meteorite] NWA7635 — wait, that sounds familiar, so I go into my living room and look at the little plaque that I have, because of course, I have it in a little display case, and that's my meteorite.

Jim Green: Hang onto it!

Andy Weir: Well, I'm not going to be giving it away. It cost a lot.

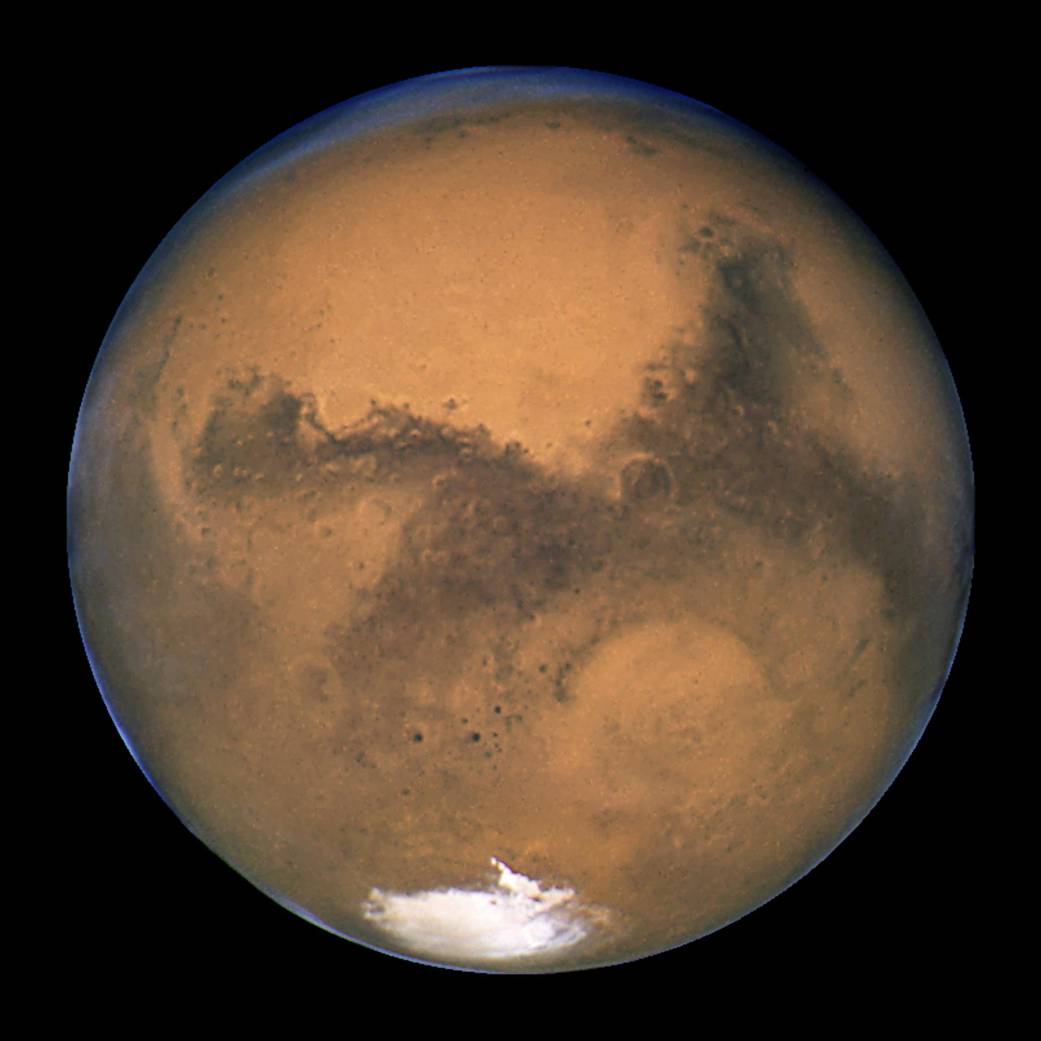

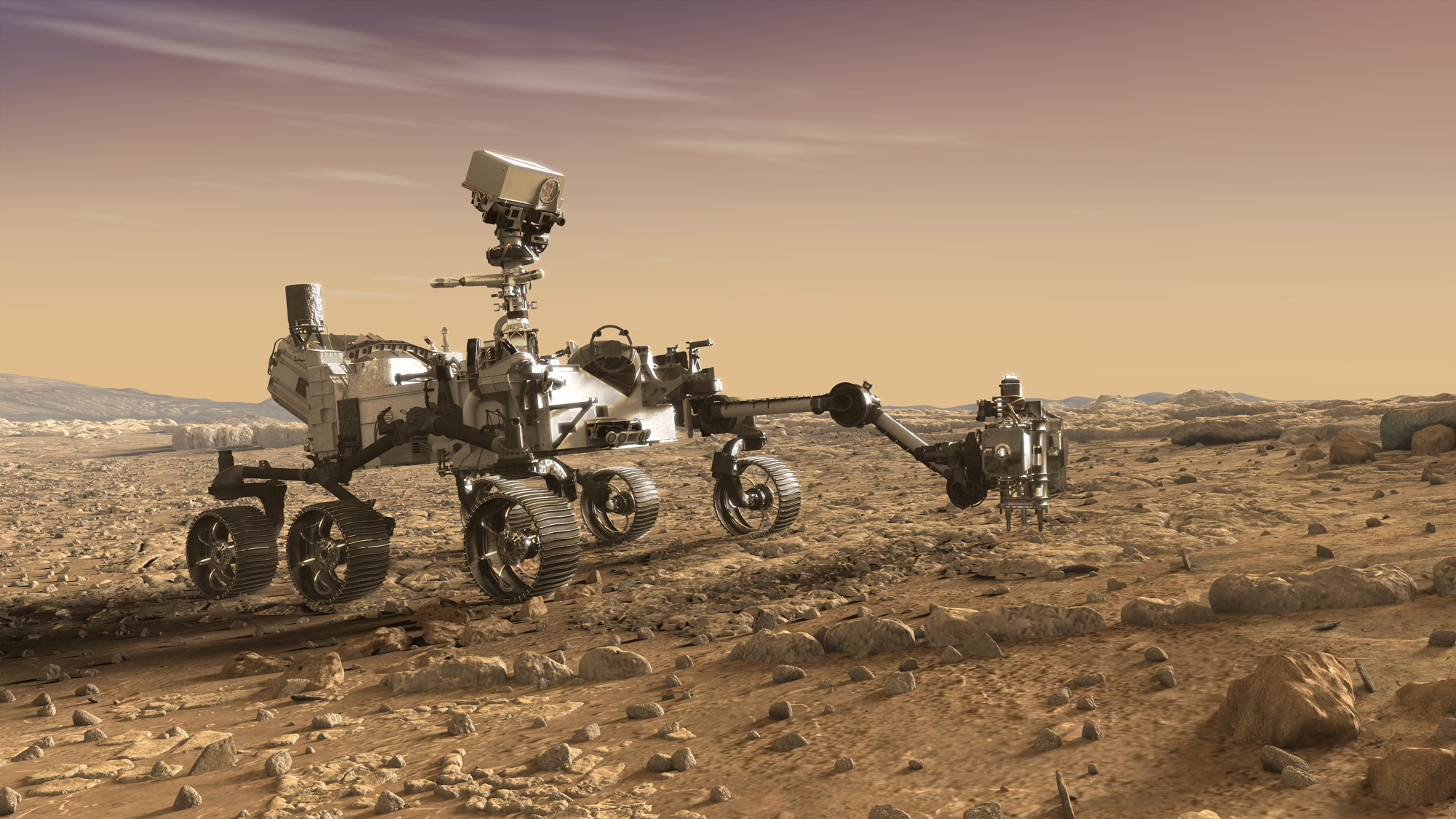

Jim Green: That's true. It may have other secrets to behold. This is really important why we need to do that next Mars mission, the sample return mission. We're going to core rock, and we're going to bring that back, and that's going to tell us how fast the climate on Mars changed.

Andy Weir: That sounds fantastic.

Jim Green: It's called Mars 2020.

Andy Weir: I'm still catching up on some of the details. That will collect the samples and leave them behind for a future return mission?

Jim Green: Once we land it in a geologically diverse area — probably where the water has modified the minerals, where the ancient shoreline on Mars has been — we'll start coring rock. It cores about a three-inch-long chalk-like cylindrical, a core sample, and it puts them into a metal sleeve, and after it does several of those, it lays them in a pile and moves on. Then later on, we're going to come and pick them up, take them back to a Mars ascent vehicle. Then we'll bring it all back [to Earth] because we really want to interrogate those [samples] in the laboratory. That's where the gold is, in bringing back those samples and really studying them.

Andy Weir: Yeah, I mean, you guys are sending entire laboratories to Mars to look at the samples, but, boy, they're nothing compared to what we can do on Earth with the facilities here.

Jim Green: Right now we call it Mars 2020, but next year [2019] we're thinking about having some sort of contest where kids from across the country can name it.

Andy Weir: Sure. That's how you named Curiosity.

Jim Green: And Spirit and Opportunity and Sojourner. So, that's an important next step that we'll do.

Andy Weir: You know, they're just going to call it 'Marsy McMarsFace'. I mean, that's going be like the top voted one. That's the thing now.

Jim Green: Well, we hope not! But I'm sure we'll get that as an entry, and it'll be from Andy Weir, at least.

Andy Weir: Oh, no, I'll be much nicer than that.

Jim Green: What I really enjoyed in The Martian is the concept of what happens when humans first get to Mars. Why did you pick the era that's just around the corner to write about?

Andy Weir: Well, I wanted it to take place as close to the modern day as possible, but I needed to give enough time in the fictional future to actually develop the technologies that would be necessary. The main kind of tech that's in The Martian that we don't have in reality yet is the strength of the ion drive that Hermes uses. Like, the technology's all proven. It works, but we don't have anything like the scale that would be necessary for it. So, I gave us about 20 years to work that out.

Jim Green: The art direction in the movie, the things that [Production Director] Art Max did, was really spectacular.

Andy Weir: Absolutely beautiful.

Jim Green: What was it like to see The Martian in the theater for the very first time?

Andy Weir: Oh, man, it was great. [Twentieth Century] Fox brought me onto their lot, and we watched it in one of those little, you know, test theater rooms where they watch it internally. The first cut that I saw was missing most of its special effects, so it's just a bunch of people walking around in front of green screens, or big obvious black wires holding them up in the zero-G scenes. But still, I'll tell you, right at the beginning, when it started that intro and it put 'The Martian' up on screen, I cried.

Jim Green: Tell me about your new book, Artemis.

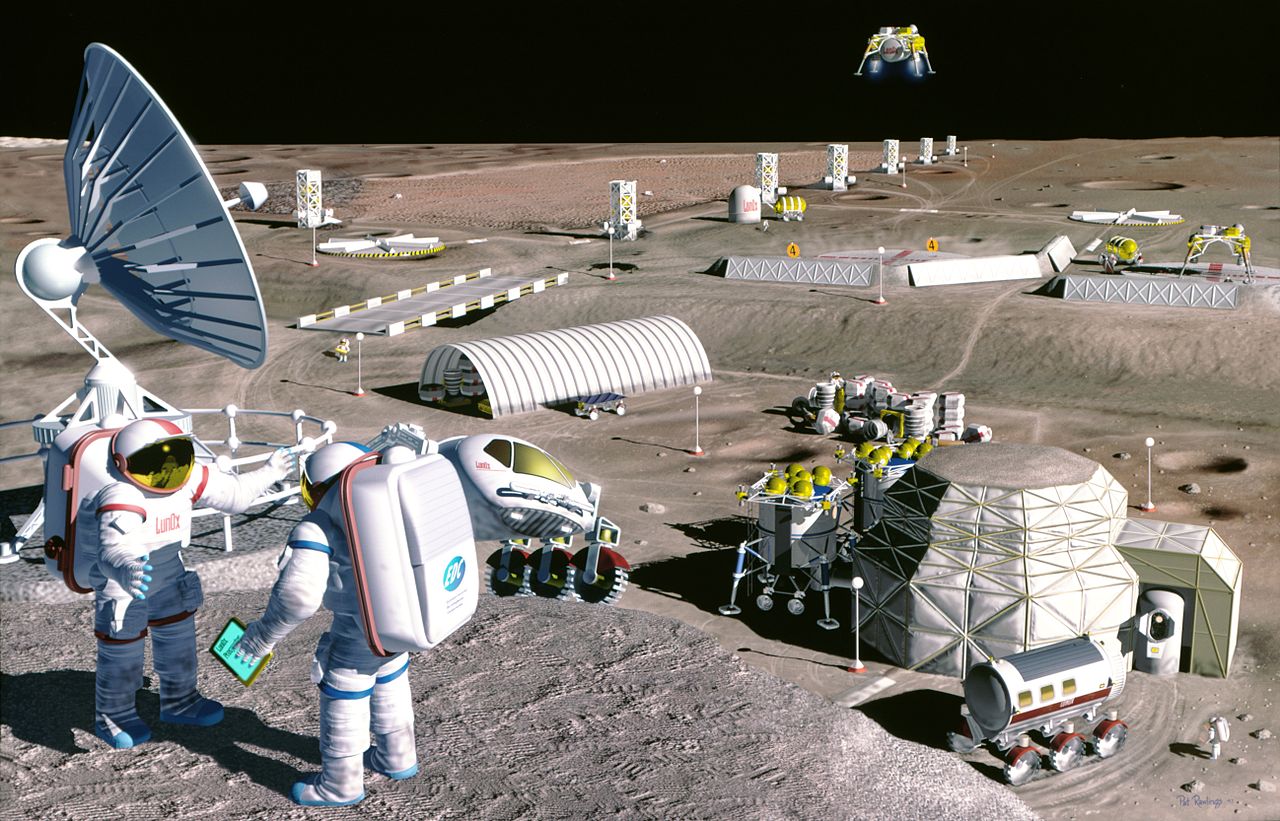

Andy Weir: Artemis takes place in a city on the Moon, humanity's first off-Earth city. And the main character is a woman who's a small-time criminal, and she gets in way over her head.

Jim Green: Way over her head, I might add.

Andy Weir: It's less about national space exploration and more about the colonization of space, so the stuff that happens a little bit later on. I had to come up with an economic reason why the city of Artemis exists and so on.

Jim Green: I thought you did it really well. It's very exciting to see how, as a science fiction writer, you can think about the future. I always say, if we don't spend time thinking about our future, we don't have a future, and I think science fiction plays a very important role in that.

Andy Weir: Every reality starts with a dream, right?

Jim Green: What kind of lunar science research did you do to help write that book?

Andy Weir: Well, quite a lot. Actually, the vast majority of that information came from the Apollo missions. Mainly, I needed to know the mineral breakdown of the ores that are available on the surface. What I learned was just amazing. I had no idea that the Moon was being so cooperative in us colonizing it. Eighty-five percent of the rocks in the lunar highlands are anorthite, which is aluminum, silicon, calcium and oxygen all put together into a very stable molecule. If you can break that apart, you end up with aluminum to build your Moon city and oxygen to fill it. I mean, the Moon is made of moon bases, just some assembly required. That was just the most awesome part. From there, I'm like, okay, how do I smelt anorthite? It takes a ludicrous amount of energy. Okay, fine, we're going to need a ludicrous amount of energy, we're going to need some [nuclear] reactors. It would be cheaper to ship the entire city to the Moon than it would be to ship the solar panels necessary to smelt anorthite, so it's going to have to be a reactor. I just kind of built out from there how the city got built and how it grew and how to make maximum use of the resources on the Moon. In fact, they would generate so much oxygen that the people in the city can't breathe it fast enough. They'd be venting it out into space. And oxygen is really handy. For every kilogram of hydrogen you want to bring to the Moon, you can make nine kilograms of water.

Jim Green: This is really thinking ahead in the sense that just in the last few years, there's been quite a bit of thinking about how to go out into our Solar System, go to the asteroids, potentially go to the Moon and be able to mine and get those resources. I think your book goes right at that very important point. That's in our future.

Andy Weir: Well, possibly, although to be fair, all of their mining and resource collection is to build the city itself. So, that works out to be economically neutral for them. It's like they get the resources from the Moon, they use the resources on the Moon. They don't really export it to Earth. It's still cheaper even within the setting of Artemis to just mine whatever you want on the planet you're on.

Jim Green: Well, indeed. Typically, the concept is we would want to mine material and then use it in that framework, use it in space. So having space helps sustain us as we move out. It's a critical new way of thinking about how to go well beyond low-Earth orbit, and I think your book really hits that.

Andy Weir: Thanks. Yeah, it's building out infrastructure, right? It's no different than the westward expansion. You don't go straight to California. You build railroad stations along the way.

Jim Green: Some people ask, why go back to the Moon? I think, as you point out in the book, there's all kinds of different reasons.

Andy Weir: The whole conceit of Artemis is based on [the fact that] it takes place in the 2080s timeframe, when the price [of reaching] low-Earth orbit has been driven down, and it's been driven down far enough that middle class people can afford to go to space. Once you have that, you have economics in space. You have a tourist destination. Artemis is 40 kilometers away from the Apollo 11 landing site, aka Tranquility Base, and there's a visitor center built there. So, you stay in pressure and look through windows at it. And the historical site is, of course, very well-protected and they don't let anybody mess with it.

Jim Green: What kind of advice do you have for those budding science fiction writers that would follow your footsteps?

Andy Weir: Well, I guess for not just science fiction but any writers, the first step is you have to actually write. You can get stuck in world building and day dreaming and planning it out forever, but you're not actually writing until you're putting words into your word processor. So, you have to actually sit down and do it, and that's when you start to notice the problems. That's why it's not fun. It's fun to sit there and go like, oh, this will be my five book series. But, when you start writing it, you're like, oh, I see all the problems now. So, that's step one.

Step two, and this is difficult but more important, is to resist the urge to tell your story to your friends and family, especially if it's good. It's even worse if it's good because they'll be, wait, and then what happens, oh, tell me more, tell me more. You have to not do that.

The reason is most writers are driven by a desire to have an audience. We want other people to experience the stories that we've created and by telling the story to people verbally, it satisfies that need and saps your will to actually write the thing. So, if you make yourself a rule that says, okay, no one can find out anything about my story except by reading it, then that motivates you, at the very least to say, okay, I'll finish this chapter, and then I'll give it to my buddy to get his feedback, and so on.

Jim Green: Well, you know, that must be the case because I think while we had chit-chatted at a couple of events about The Martian at various stages along the way, I had asked you about your next book, and you were—

Andy Weir: I was cagey.

Jim Green: Well, you were pretty darned cagey. I couldn't get any information out of you on that. I assume you're working on another project?

Andy Weir: My next project--well, this is my plan is that my next project would be a follow up book to Artemisthat also takes place in Artemis, but Jazz [the character Jasmine 'Jazz' Bashira] is not the main character. It's a different person, and it's a different story. I would love to write a bunch of stories that all take place in Artemis as it goes forward through its own history.

Jim Green: Now there's quite a bit of thinking about how the Moon, or at least being near the Moon in what's called a (Deep Space) Gateway, could help us move to Mars. I think what we'll see over the next few years is a lot more thinking about going back to the Moon and doing a variety of science.

Andy Weir: I think the Moon would be a fantastic stepping stone on the way to Mars, because if Artemis really existed, a manned Mars mission would be monumentally easier because you have this entire infrastructure, including fuel generation and metal working and everything like that, in a gravity well that's considerably lower than Earth's.

Jim Green: Do you have any plans [in your future writing] to go back to Mars?

Andy Weir: Well, I don't know. I mean, not as a sequel to The Martian. I may have things take place on Mars in the future, but The Martian is sort of a "one-and-done" story. I have never been able to come up with an idea for a sequel to it that wasn't stupid. It's like if Mark Watney gets in trouble again, well, NASA starts to look really incompetent, right? And if somebody else is in trouble and Mark is helping, then Mark isn't really the main character any more. People really liked Mark, so I just don't see any way to make a sequel on that. But Mars itself is a setting where lots of fun stuff could happen.

Jim Green: One of the things that I really liked about the opening to The Martian was that the scientists were out deploying instruments, the astronauts were doing a variety of things, and Mark was picking up samples, and he was throwing a little dirt in his little box. I would have loved, as he goes back and gets his helmet for the last time to leave the station, Ares 3, that he picks up that file and takes it with him.

Andy Weir: Well, actually, in the book he remained an astronaut and a scientist throughout the whole ordeal during his long trip from Acidalia [Planitia] to Schiaparelli [Crater].He deliberately would still like take samples of the area, label them, tag them, put them in a box and leave them out on the surface for possible future sample returns. And I did have an idea of something like, ooh, we found something interesting, now we have to go back to where Mark was at this one point. But, still, it's hard to make a story out of that. These are things that it's really difficult because some of these things that you can imagine would be unbelievably exciting if they happened in real life are not that interesting if you write it as a story. Like if we just found there's actually la little microbe that lives on Mars, that would be the most amazing scientific discovery. But in a movie, that's like, so what? Are they going to invade? I really have to temper what would excite me compared to what would excite a mainstream audience of readers.

Jim Green: In your career, you really fell hard into the ability to write science fiction. What's changed in your life since then?

Andy Weir: Well, you know, I was writing The Martian just as sort of a labor of love. I was posting it to my website at the time. I spent 25 years as a computer programmer, a software engineer, and I really liked that, too, by the way. I enjoyed that job. Now, every aspect of my life is different. I'm a pretty social guy, and I used to really like going into work in the morning, and there were all my co-workers and, "Hey, how ya doing, can I buy you some coffee?" Now what I do is I go down to my home office, and I'm by myself, and I write. I do miss having a large group of people that I work with as part of a team. But, on the other hand, what is still probably the best week of my life was about two years ago when NASA brought me out to Johnson Space Center, and I got a week of VIP tours around everything. The access that I have gotten to various people and places as a result of The Martian — imagine this Venn diagram that's surrounded by awesome scientists, awesome writers, movie stars and then I'm right there in the middle. I get to play with all of them.

Jim Green: You're writing at a level where all the kids of this generation just eat it up. What kind of letters from kids do you get?

Andy Weir: Well, it's really cool. I had no idea when I wrote The Martian that it would be such a useful educational tool, but it turns out that it is, of course, because it's basically a long series of algebra questions and with the answers later on. I've learned that a lot of teachers are using it in the classroom. That's why we made a classroom edition with all the swearing toned down. And so, that's fantastic. I do get a lot of information about that from people and parents. I received an email just this morning from a woman whose son is severely autistic and doesn't really engage well with things, but loved The Martian and would read the book, and that was a method by which she could interact with him.

I think my favorite though was right around the time the film was out in theaters, a woman sent me a picture of her little girl's Halloween costume, and the little girl was seven or something like that, and she had dressed up as Commander Lewis from the book for, so she had her little astronaut outfit on, it said Melissa Lewis on it, and she had a cardboard box that was labeled Hermes and stuff like that. I just thought it was awesome that because of my book, this little girl decided to be an astronaut for Halloween instead of a princess, you know?

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. This version of the story published on Space.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is the U.S. government agency in charge of the civilian space program as well as aeronautics and aerospace research. Founded in 1958, NASA is a civilian space agency aimed at exploring the universe with space telescopes, satellites, robotic spacecraft, astronauts and more. The space agency has 10 major centers based across the U.S. and launches robotic and crewed missions from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral Florida. Its astronaut corps is based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. To follow NASA's latest mission, follow the space agency on Twitter or any other social channel, visit: nasa.gov.