Spring Will Light Up the Night Sky with Dazzling 1st-Magnitude Stars

With the arrival of spring, we can step out during the late evening hours (around 11 p.m. local daylight time) and count up to 11 "first magnitude" stars – the brightest in the sky. At no other time of the year can we see this many bright stars at one time. But while this initially might sound impressive, the truth is that seven of these bright twinklers belong not to stars associated with spring, but with the departing stars of winter. Indeed, Orion the Hunter and its bright retinue are slowly departing the scene, dropping progressively lower each evening in the western sky.

Two of the remaining four bright stars actually adorn the warm nights of summer: Vega in the constellation of Lyra, the Lyre that is low in the northeast, and Deneb, marking the tail feathers of Cygnus, the Swan, just coming up above the northeast horizon. [Vernal Equinox 2018! See the 1st Day of Spring from Space]

The final two stars are the lone bright stars of the spring season: Spica in the constellation of Virgo the Virgin, is over toward the southeast part of the sky, and Regulus, which marks the heart of Leo the Lion. The rest of the firmament contains stars that are generally medium to dim in overall brightness. There are, of course, a few conspicuous star patterns, such as the famous Big Dipper that appears upside-down high in the north, and the backward question-mark grouping of stars that outlines the head and mane of Leo, popularly known as the Sickle.

When I give sky shows at New York's Hayden Planetarium, I often tell my audiences that they can always find Leo by first locating the Big Dipper and then imagining that the bowl is filled with water. "Now pretend," I would tell my audience, "that you've drilled a hole in the bottom of the Dipper and you allow all that water to spurt out through that hole. Who would get wet?

It would be Leo, with the water falling on his head, which is where you would find the famous Sickle.

Three dogs but no cats

During the 18th century, some star atlases depicted a cat: Felis, the creation of the French astronomer Joseph Jérôme Le Francais de Lalande. He explained his choice: "I am very fond of cats. I will let this figure scratch on the chart. The starry sky has worried me quite enough in my life, so that now I can have my joke with it." [Constellations of the Night Sky: Famous Star Patterns Explained]

Incidentally, "Felis" means cat in Latin, and I always used to wonder whether the famous cartoon character "Felix the Cat" somehow owes his name to Felis. Felix, however, is derived from the Latin word felicis, which means "happy." So, while the two names sound somewhat alike, they have different meanings.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Ultimately, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) did not take too kindly to Lalande's "joke." Felis did not make the cut when the IAU created the now current "official" listing of 88 constellations in 1930. However, cat lovers can be consoled by the fact that along with Leo, there are two other members of the cat family that are near to each other in the current evening sky, albeit rather faint: Leo Minor, the Little Lion and Lynx.

I'll have more to say about Lynx in a moment.

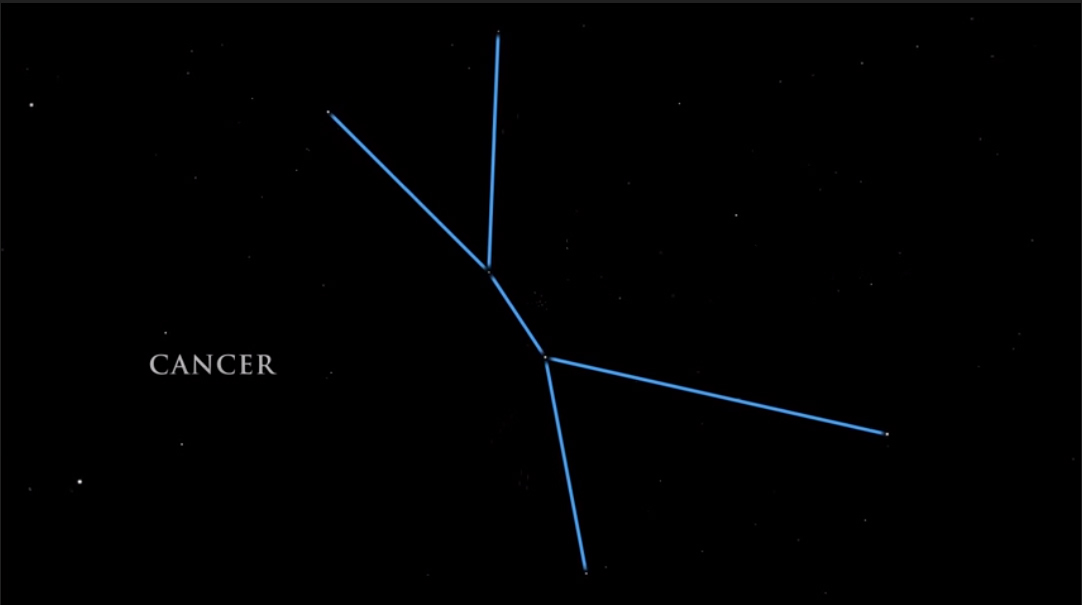

An unfortunate crustacean

Of the 12 zodiacal constellations, the dimmest is now soaring high in the south: Cancer the Crab. So faint are the stars that comprise this star pattern, we might refer to Cancer as an empty space in the sky. Because it contains no star brighter than 4th magnitude, the crab is difficult, if not impossible, to see under a light-polluted sky.

Cancer is essentially a Greek creation. This creeping creature was sent by Zeus' jealous wife, Juno, to fatally bite Hercules, Zeus' son from his liaison with Alcmene. The crab arrived just as Hercules was battling the multiheaded Hydra, one of his assigned 12 "labors." The crab obeyed Juno's orders, but its bite was no more than a mere annoyance to Hercules, who was much too busy to look where his was stepping. As Hercules backpedaled, he ended up crushing Cancer under his heel.

Juno then placed the hapless little crab in the sky as a reward for his services, but failed to adorn it with any conspicuous stars and thus this unfortunate crustacean has been almost invisible ever since.

Dim cats

Now back to Lynx, one of only two animal constellations (the other being Phoenix) that has identical Latin and English names. With only one 3rd magnitude star, Lynx is similar to Cancer in that it is one of the hardest constellations to find, much less visualize as what it supposedly represents. [Find the Felines: Cats in the Night Sky]

Johannes Hevelius, a Polish astronomer, introduced this wild cat in his star atlas, which was published in 1690. In his star atlas, the allegorical drawing of Lynx depicted his brightest star in the tuft of its tail. And from these drawings it seems that nearby Leo Minor was playfully trying to bite Lynx's tail.

Like Lynx, the Little Lion is quite faint and in his book, "Exploring the Night Sky with Binoculars" (Cambridge University Press, 2000), the late, legendary British astronomer Sir Patrick Moore made reference to Leo Minor's "dubious claims to a separate identity."

Although the telescope was just coming into general use during Hevelius' time, he openly abandoned this relatively new invention. In his star atlas, he tucked a cartoon into the corner of one sky chart showing a cherub holding a card with the Latin phrase: "Optimum nudo oculo," which translated means: "The naked eye is best." In creating Lynx, Hevelius chose a cat-like animal that possesses acute eyesight.

But as we've already noted, Lynx is one of the hardest constellations to visualize. So much so, that even Hevelius himself openly admitted that you would have to have a lynx's eyes to see it!

Thus, I would suspect that in order to provide you with the incentive to go out tonight and search for Lynx will require a lot of "purr-suasion" on my part.

But he's such a faint star pattern, I wouldn't blame you if you put off that task for another night.

Just call it "pro-cat-stination."

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, NY. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.